Niall Ferguson: Somewhere a village is missing its idiot

May 5, 2013 § 1 Comment

By now it is no secret that I think Niall Ferguson is a pompous simpleton. I give the man credit, he has had a few good ideas, and has written a few good books, most notably Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power. His recent book, Civilization: The West and the Rest, would have actually been a pretty good read if not for his sophomoric and embarrassing discussion of “killer apps” developed by the West and now “downloaded” by the rest of the world, especially Asia. He has also been incredibly savvy in banking his academic reputation (though he is losing that quickly) into personal gain. He has managed to land at Harvard, he advised John McCain’s presidential campaign in 2008.

But a few days ago, Ferguson outdid himself. Speaking at the Tenth Annual Altegris Conference in Carlsbad, California, Ferguson responded to a question about John Maynard Keynes‘ famous comment on long-term economic planning (“In the long run, we are all dead”). Ferguson has made it abundantly clear in the past that he does not think highly of the most influential and important economist of all time, which is fine. But Ferguson has also made it abundantly clear that part of his problem with Keynes is not just based on economic policy. John Maynard Keynes was bisexual. He was married in 1925 to the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, with whom he remained with until his death in 1946. By all accounts I’ve read, the marriage was a happy one. But they did not have children, which obviously upsets Ferguson. But more troublesome for Ferguson is the fact that Keynes carried out many, many affairs with men, at least up to his marriage. Fourteen years ago, in one of Ferguson’s more forgotten books, The Pity of War, Ferguson goes on this bizarre sidetrack on Keynes’ sexuality in the post-WWI era, something to the effect (I read the book a long time ago) that Keynes’ life and sexuality became more troubled after the war, in part because there were no cute young boys for him to pick up on the streets of London. Seriously. In a book published by a reputable press.

So, in California the other day, to quote economist Tom Kostigen (and who reported the comments for the on-line magazine Financial Advisor), who was there:

He explained that Keynes had [no children] because he was a homosexual and was married to a ballerina, with whom he likely talked of “poetry” rather than procreated. The audience went quiet at the remark. Some attendees later said they found the remarks offensive.

It gets worse.

Ferguson, who is the Laurence A. Tisch Professor of History at Harvard University, and author of The Great Degeneration: How Institutions Decay and Economies Die, says it’s only logical that Keynes would take this selfish worldview because he was an “effete” member of society. Apparently, in Ferguson’s world, if you are gay or childless, you cannot care about future generations nor society.

Indeed. Remember, Ferguson is, at least sometimes, a professor of economic history at Harvard. That means he has gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students in his classes. How are they supposed to feel about him when they go into his class? How is any right-thinking individual supposed to think when encountering Ferguson in class or anywhere, for that matter?

Today, Ferguson apologised on his own blog. He called his comments his “off-the-cuff and not part of my presentation” what they are: stupid and offensive. So for that, I applaud Ferguson. He has publicly owned up to his idiocy. But, I seriously doubt these were off-the-cuff comments. Those are not the kind of comments one delivers off-the-cuff in front of an audience. How do I know? Because I’ve talked in front of large audiences myself. I’ve been asked questions and had to respond. Sometimes, we do say things off-the-cuff, but generally, not. The questions we are asked are predictable in a sense, and they are questions that are asked within the framework of our expertise on a subject.

Moreover, there is also the slight matter of Ferguson’s previous gay-bashing comments in The Pity of War a decade-and-a-half ago. Clearly, Ferguson has spent a lot of time pondering Keynes as an economist. But he has also spent a lot of time obsessing over Keynes’ private life which, in his apology today, Ferguson acknowledges is irrelevant. He also says that those who know him know that he abhors prejudice. I’m not so sure of that, at least based on what I’ve read of Ferguson’s points-of-view on LGBT people, to say nothing of all the non-European peoples who experienced colonisation at the hands of Europeans, especially the British. Even in Empire, he dismissed aboriginal populations around the world as backwards until the British arrived.

I do not wish Ferguson ill, even though I do not think highly of him. But I do hope there are ramifications for his disgraceful behaviour in California this week.

Stephen Harper: Revisionist Historian

May 3, 2013 § Leave a comment

By now, it should be patently clear that Canada’s Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, is not a benign force. He likes to consider himself an historian, he’s apparently publishing a book on hockey this fall. But, I find myself wondering just what Harper thinks he’s doing. I’ve written about the sucking up of the Winnipeg Jets hockey club to Harper’s government and militaristic tendencies. I’ve noted Ian McKay and Jamie Swift’s book, Warrior Nation: The Rebranding of Canada in the Age of Anxiety (read it!). And I’ve had something to say about Harper’s laughably embarrassing attempt to re-brand the War of 1812 to fit his ridiculous notion of Canada being forged in fire and blood.

Now comes news that Harper’s government has decided it needs to re-brand Canadian history as a whole. According to the Ottawa Citizen:

Federal politicians have launched a “thorough and comprehensive review of significant aspects in Canadian history” in Parliament that will be led by Conservative MPs, investigating courses taught in schools, with a focus on several armed conflicts of the past century.

The study was launched by the House of Commons Canadian heritage committee that went behind closed doors last Monday to approve its review, despite apparent objections from the opposition MPs.

When this first passed through my Twitter timeline, I thought it HAD to be a joke. But it’s not. Apparently, Harper thinks that Canada needs to re-acquaint itself with this imagined military history. I’m not saying that Canadians shouldn’t be proud of their military history. We should, Canada’s military has performed more than admirably in the First and Second World Wars, Korea, and Afghanistan, as well as countless peacekeeping missions. Hell, Canadians INVENTED peacekeeping. Not that you would know that from the Harper government’s mantra.

As admirable as Canada’s military has performed, often under-equipped and under-funded, it is simply a flat out lie to suggest that we are a nation forged of war, blood, and sacrifice. Canada’s independence was achieved peacefully, over the course of a century-and-a-half (from responsible government in 1848 to the patriation of our Constitution in 1982). And nothing Harper’s minions can make up or say will change that, Jack Granatstein be damned.

To quote myself at the end of my War of 1812 piece:

Certainly history gets used to multiple ends every day, and very often by governments. But it is rare that we get to watch a government of a peaceful democracy so fully rewrite a national history to suit its own interests and outlook, to remove or play down aspects of that history that have long made Canadians proud, and to magnify moments that serve no real purpose other than the government’s very particular view of the nation’s past and present. The paranoiac in me sees historical parallels with the actions of the Bolsheviks in the late 1910s and early 1920s in Russia. The Bolshevik propaganda sought to construct an alternate version of Russian history; in many ways, Canada’s prime minister is attempting the same thing. The public historian in me sees a laboratory for the manufacturing of a new usable past on behalf of an entire nation, and a massive nation at that.

Every time I read about Harper’s imaginary Canadian history, I am reminded by Orwellian propaganda. And I’m reminded of the way propaganda works. Repeat something often enough, and it becomes true. The George W. Bush administration did that to disastrous effects insofar as the war in Iraq is concerned. But today, I came across something interesting in Iain Sinclair’s tour de force, London Orbital, wherein Sinclair and friends explore the landscape and history of the territory surrounding the M25, the orbital highway that surrounds London. Sinclair is heavily critical of both the Thatcherite and New Labour visions of England. In discussing the closing of mental health hospitals and the de-institutionalisation of the patients in England, Sinclair writes:

That was the Thatcher method: the shameless lie, endlessly repeated, with furious intensity — as if passion meant truth.

I suppose in looking for conservative heroes, Harper could do worse than the Iron Lady. But it also seems as if Harper is attempting nothing less than the re-branding of an entire nation.

On Libertarianism

May 1, 2013 § 4 Comments

Libertarianism is a very appealing political/moral position. To believe and accept that we are each on our own and we are each able to take care of our own business, without state interference is a nice idea. To believe that we are each responsible for our own fates and destinies is something I could sign up for. And, I have to say, the true libertarians I know are amongst the kindest people I know, in terms of giving their time, their money, their care to their neighbours and community, and even macro-communities.

But there are several fundamental problems with libertarianism. The first problem is what I’d term ‘selfish libertarianism.’ I think this is what drives major facets of the right in the Anglo-Atlantic world, a belief in the protection of the individual’s rights and property and freedom of behaviour, but coupled with attempts to deny others’ rights, property, and freedom. This, of course, is not real libertarianism. But this is pretty common in political discourse these days in Canada, the US, and the UK. People demand their rights to live their lives unfettered, but wish to deny others that freedom, especially women, gays/lesbians, and other minority groups (of course, women are NOT a minority, they make up something like 53% of the population in Canada, the US, and UK). So, ultimately, we can dismiss these selfish libertarians as not being libertarians at all.

My basic problem with true libertarianism is its basic premise. If we are to presume that we are responsible for our own fates and destinies, then we subscribe to something like the American Dream and that belief we can all get ahead if we pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and work hard. I find that very appealing, because I have worked hard to get to where I am, and I feel the need to keep working hard to fulfill my own dreams.

But therein lies the problem. Behind the libertarian principle is the idea that we’re all on the same level playing field. We are not. Racism, classism, homophobia, sexism, misogyny: these all exist on a daily basis in our society. I see them every day. I have experienced discrimination myself. And no, not because I’m Caucasian. But because I come from the working-classes. I was told by my high school counsellor that my type of people was not suited for university studies. I had a hard time getting scholarships in undergrad because I didn’t have all kinds of extra-curricular activities beyond football. I didn’t volunteer with old people, I didn’t spend my time helping people in hospitals. I couldn’t. I had to work. And I had to work all through undergrad. And throughout my MA and PhD. In fact, at this point in my life at the age of 40, I have been unemployed for a grand total of 5 months since I landed my first job when I was 16. And having to work throughout my education simply meant I didn’t qualify for most scholarships. So I had to work twice as hard as many of my colleagues all throughout my education. And that, quite simply, hurt me. And sometimes my grades suffered. And within the academy, that is still problematic today, even four years after I finished my PhD. But that’s just the way it is. I can accept that, I’m not bitter, I don’t dwell on it. But it happened, and it happened because of class. Others have to fight through racism or sexism or homophobia.

So, quite simply, we do not all begin from the same starting line. We don’t all play on a level playing field. Mine was tilted by class. And, for that reason, libertarianism, in its true sense, does not work. If we wish to have a fair and just society, we require ways and means of levelling that playing field, to give the African-American or working class or lesbian or son of immigrant children the chance to get ahead. Me? I worked hard, but I also relied on student loans, bursaries, and what scholarships I could win based on grades alone. My parents didn’t pay for a single cent of my education, not because they didn’t care or want to, but because they simply couldn’t afford it. I got some support from my grandparents each year, to go with the student loans/bursaries/small scholarships. And thank god I did. Otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to do it. I’d be flipping burgers at a White Spot in Vancouver at the age of 40.

On Humanity and Empathy: Boston and Rehtaeh Parsons

April 18, 2013 § Leave a comment

Monday’s terrorist attack at the Boston Marathon was a little too close to home for my tastes. A few of my students were there, near the finish line. A couple had left by the time the bombs went off, a couple had not. They were unhurt, as they were far enough away from the bombs. I know Boylston Street well. A few days before the Marathon, I was there; I had dinner in the Irish pub in the Lenox Hotel, which is across the street from where the second bomb went off. In my mind’s eye, I can see exactly where those two bombs were.

Like most Canadians and Americans, for me terrorism happens in the abstract. It’s a news report on TV, it’s on our Twitter timelines, it’s pictures in a newspaper. Sometimes, it’s a movie. But we don’t experience it personally, and this is still true even after 9/11. I have not experienced terrorism personally, and yet, I have never been as close to a terrorism attack as I was on Monday. Not surprisingly, I feel unsettled.

But I have been shocked and dismayed by some of the responses to the bombs on Boylston Street. Aside from those on Twitter declaring this to be a “false flag” attack (in other words, a deliberate attack by the US government on its people), which is stupid to start with, there have also been those who have been declaring that this happens all the time in Kabul or Baghdad or Aleppo. That is very true, it does happen everyday in those places. Indeed, for far too many people around the world, terrorism is a daily fact of life. That is wrong. No one should live in terror. But by simply declaring that this happens all the time elsewhere, you are also saying that what happened in Boston doesn’t matter. And that is a response that lacks basic humanity.

This has been a week where I’ve been reminded too often about our lack of humanity. The inhumanity of the bombers, of the conspiracy theorists, and those who say this doesn’t matter because it happens all the time elsewhere.

News also broke this week about disgusting, inhumane behaviour surrounding the Rehtaeh Parsons case in Halifax. There, “friends, family, and supporters” (to quote the CBC) have taken to putting up posters in the neighbourhood around Parsons’ mother’s house supporting the boys who sexually assaulted her, declaring that the truth will come out. I’m sure those boys are living in a world of guilt and shame right now, as they should. But to continue to terrorise a woman whose daughter was sexually assaulted, and then teased, mocked, and bullied for two years until she took her life is inhumane. It is inhumane that those boys assaulted Rehteah in the first place. It is inhumane that her classmates harassed, mocked, and bullied her for two years for being a victim.

There has been plenty of positive, especially in response to the Boston bombings. As I write this, President Obama is at a memorial service in Boston for the victims of the bombing. There are plenty of stories of the humanity of the response of the runners of the marathon, the bystanders, and the first responders. #BostonStrong is a trending hashtag on Twitter. Jermichael Finley of the Green Bay Packers will be donating $500 for every dropped pass and touchdown to a Boston charity, and New England Patriots receiver will donate $100 for every reception and $200 for every dropped pass this season. Last night’s ceremony at the TD Garden before the Bruins game was intense. And so on and so forth. This is all very heartening. It shows that we are humane, that we can treat each other with empathy and sympathy and dignity.

But it doesn’t erase those who lack humanity. I had a Twitter discussion last night about this. About how this kind of inhumanity seems to be everywhere. This morning, I was talking to two students about this inhumanity and how it just makes us depressed and wanting to cry. I wish I could say that this is a new phenomenon in society. But it’s not. This is one of the (dis)advantages to being an historian. We have the long view of history, quite obviously. We have always been a vengeful, inhumane lot. We’ve used torture since we could walk on our hind legs. The Romans’ favourite past-time was gladiator fighting, where two men fought to the death. Public executions were big deals, social outings. All to watch a man (and occasionally a woman) die. What is different now is the Internet allows people to express their inhumanity so much easier and so much quicker, and to gain further exposure in so doing. And that is just unfortunate.

Wither the Working Classes?

April 7, 2013 § 3 Comments

South Boston is undergoing massive redevelopment these days, something I’ve already noted on this blog. Every North American city has a Southie, a former industrial working-class neighbourhood that is undergoing redevelopment in the wake of deindustrialisation and the gentrification of inner cities across the continent. In Montréal, the sud-ouest is ground zero of this process, something I got to watch from front-row seats. In Vancouver, it was Yaletown. Cities like Cleveland and Pittsburgh have done brilliant jobs in re-claiming these post-industrial sites. In Boston, however, Southie’s redevelopment has attracted the usual controversy and digging in by those working-class folk who remain there. It’s even the locale of a “reality” TV show that is more like working-class porn than anything else.

The same discourse always emerges around these post-industrial neighbourhoods under redevelopment, something I first noticed in my work on Griffintown in Montréal. Today, in the Boston Globe there is a big spread ostensibly about a sweet deal given to a Boston developer by City Hall, but is really more an examination of the redevelopment of Southie’s waterfront. In in, James Doolin, the chief development officer of the Port Authority of Massachusetts, one of the players in this redevelopment, reflects on the ‘new buzz’ surrounding the area, going to to talk about how this ‘speaks to a demographic that is young, employed, and looking for social spaces.”

Right. Because the Irish who lived and worked in Southie during its life as an industrial neighbourhood were really just bums, always unemployed and so on. And, of course, those unemployed yobs would never look for social spaces, all those little cretins hung out in back alleys and under expressways. This attitude is unfortunate and is part and parcel when it comes to the redevelopment of these neighbourhoods: the belief that the working classes never had jobs, had no social lives and were just drones. I’ve seen it in literature from developers in Griffintown and other parts of Montréal’s sud-ouest, so it’s no surprise to find this attitude in Boston. But it doesn’t make it right. In one sweeping, gross over-generalisation, Doolin (and the Boston Globe) sweep away centuries of history, of life in Southie, and the day-to-day struggles of the working classes in the neighbourhood to survive and live their lives on their terms.

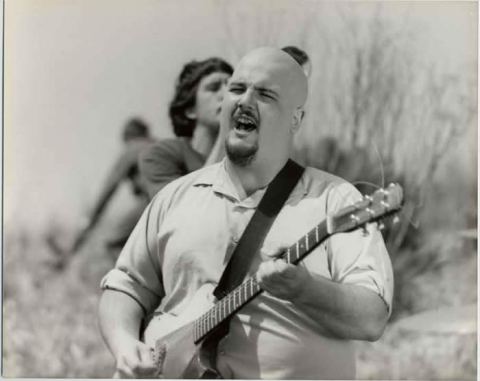

“We Jam Econo” D Boon and the Minutemen

February 8, 2013 § 1 Comment

While laid up sick this week, I finally got to see “We Jam Econo: The Story of the Minutemen,” about the iconic punk band, the Minutemen. The Minutemen came to an untimely end on 22 December 1985 when frontman and guitarist, D Boon, was killed in a car accident just outside Tucson, Arizona, as he and his girlfriend made their way to visit her family for Christmas. The other two members of the Minutemen, bassist Mike Watt and drummer George Hurley, were devastated, of course. To this day, everything Watt produces is dedicated to D boon’s memory.

I first got into the Minutemen a few years later, around 1990 or so when I got my hands on fIREHOSE’s 1989 album, fROMOHIO. This was the band that Watt and Hurley formed in the aftermath of D. Boon’s death with Ed Crawford. I was drawn to the mixture of Crawford’s jazzy guitar, combined with Watt’s amazing bass sounds. But, what attracted me the most was Hurley’s drumming. I honestly don’t think there’s another drummer I’ve ever heard that touched Hurley, except for maybe Jimmy Chamberlin in the Smashing Pumpkins. But as I obsessed about fIREHOSE, I was directed towards the Minutemen by one of the guys who worked at the old Track Records on Seymour Street in downtown Vancouver.

I first got into the Minutemen a few years later, around 1990 or so when I got my hands on fIREHOSE’s 1989 album, fROMOHIO. This was the band that Watt and Hurley formed in the aftermath of D. Boon’s death with Ed Crawford. I was drawn to the mixture of Crawford’s jazzy guitar, combined with Watt’s amazing bass sounds. But, what attracted me the most was Hurley’s drumming. I honestly don’t think there’s another drummer I’ve ever heard that touched Hurley, except for maybe Jimmy Chamberlin in the Smashing Pumpkins. But as I obsessed about fIREHOSE, I was directed towards the Minutemen by one of the guys who worked at the old Track Records on Seymour Street in downtown Vancouver.

The Minutemen blew my mind. D. Boon’s was already legendary. Vancouver had been central to the development of North American punk in the late 70s, and the city’s biggest band, DOA, had shared several bills with the Minutemen down in California. Track Records even had a Minutemen poster on the wall. I quickly became obsessed with the Minutemen’s 1984 double album, Double Nickels on the Dime. I loved Watt’s explanation of how this title came about; it was a response to Sammy Hagar’s complaint that he couldn’t drive 55. Apparently ‘double nickels” means 55mph, the speed limit in those days.

Every time I listen to the Minutemen these days, I just get incredibly sad. D Boon has been dead for longer than he was alive by this point, he was 27 when he died 28 years ago. Watt has aged, he still makes incredible music. But, simply put, and as trite as it sounds, D Boon never got a chance to age. His music always had a sneer in it, but what I loved most was always his political bent. He was a good working class boy (as were Hurley and Watt), and the politics of the working classes pervade his music. I was always drawn to this as a working class kid myself. In fact, this is what drew me to punk in the first place, it was a working-class movement. D Boon sang about how the working classes got screwed, his music reflected his own values of hard work, something instilled in him by his mother, who had died young herself, in 1978. More than that, D Boon was articulate, he didn’t look like a dumb punk trying to find big words when he spoke, he sounded like a smart working class dude. I liked that most about him. Too many other working class punks sounded like stupid mooks when they spoke (I’m looking at you, Hank Rollins).

But the Minutemen weren’t just anger. Their music was smart, a mixture of punk, funk and jazz, anchored by the incredible skill of Hurley. This jazz and funk influence (especially through Watt’s bass) added a level of fun and bounce to the music that other punks lacked. And Watt and D Boon were also just as influenced by The Who and Credence as anything else. These influences made them probably the most musically and technically proficient punk band of the era. They also mellowed as they got older, as both D Boon and Watt grew into their talent. This is what makes Double Nickel so sad for me (to say nothing of Three Way Tie (For Last), their last album, which came out a week or two before D Boon died). The Minutemen were evolving away from punk, they still sounded so unlike anything else out there. They weren’t becoming a basic rock band, they were far too smart for that.

Watt carries this spirit on in everything he does. His bass guitar was instrumental to the Minutemen’s sound. This is precisely what makes it all so sad, I always imagine what Watt would sound like if he and D Boon and George Hurley were still making music together. The Rolling Stone review of Three Way Tie (For Last) prophecies that “You can bet that in ten years there’ll be groups who sound like the Minutemen — maybe they’ll even cover their songs.” In 1996, no one sounded like the Minutemen. In 2006, no one sounded like the Minutemen. And in 2016, no one will sound like the Minutemen. They were a unique, one of a kind band.

This last clip comes from an interview the Minutemen did in the early fall 1985, just a few months before D Boon checked out.

Boston’s Architectural Behemothology — UPDATED

February 5, 2013 § 3 Comments

Government Center, downtown Boston. It is rare to see such a massive, overwhelming failure of this sort anywhere. Standing outside the T station last fall, I looked across the windswept brick City Hall Plaza, amazed that anyone ever thought this kind of brutalist behemethology was a good idea. Especially in a city like Boston that generally boasts beautiful architecture from the colonial era forward. Indeed, from Government Center, it’s just a few minutes’ walk to Faneuil Hall and the Old State House, or Beacon Hill, or the Common and Public Gardens. Boston’s public spaces are always full of people, tourists and Bostonians taking in the sights and the vibe. The city has even done a great job rehabilitating the old waterfront around Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park. Hell, even the park space over what was the Big Dig and the buried I-93 is used. But City Hall Plaza? There wasn’t a single soul on that desert of hideousness. Not a one. And, looking at this image, you can see why.

Government Center, downtown Boston. It is rare to see such a massive, overwhelming failure of this sort anywhere. Standing outside the T station last fall, I looked across the windswept brick City Hall Plaza, amazed that anyone ever thought this kind of brutalist behemethology was a good idea. Especially in a city like Boston that generally boasts beautiful architecture from the colonial era forward. Indeed, from Government Center, it’s just a few minutes’ walk to Faneuil Hall and the Old State House, or Beacon Hill, or the Common and Public Gardens. Boston’s public spaces are always full of people, tourists and Bostonians taking in the sights and the vibe. The city has even done a great job rehabilitating the old waterfront around Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park. Hell, even the park space over what was the Big Dig and the buried I-93 is used. But City Hall Plaza? There wasn’t a single soul on that desert of hideousness. Not a one. And, looking at this image, you can see why.

Government Center is, well, the centre of government in Boston, this perfect amalgam of city, county, and state government on one location. Government Center looms over downtown Boston like some horrible spaceship from the nightmares you have as a child. The New England Holocaust Memorial is just across Congress St. from Government Center. As I walked through the memorial, which is one of the most effective I’ve seen, I couldn’t help but feel the spectre of Government Center on me. Even as we walked on to Faneuil Hall, Government Center loomed above. It reminded me of that strange ball that followed No. 6 around in The Prisoner, keeping him from ever finding happiness or freedom.

Yes, Government Center is that bad. It sucks joy from the air around it. It stands as an insult against everything that surrounds it. It is, as a friend (an architect) would call it, an aesthetic insult. City Hall Plaza is bad, no doubt, but as that name indicates, there is a City Hall that comes with it. Boston’s City Hall is, not surprisingly, a horrible piece of brutalism, designed to intimidate the poor citizen standing outside of it. Every time I pass it, I imagine a cartoon of some poor, downtrodden sod standing in front of a faceless bureaucracy. Brutalist architecture is designed to be imposing and intimidating. And Boston is certainly not the only city to be marred by this abomination. University campuses are particularly good examples of brutalism, as I have noted elsewhere on this blog.

Winnipeg is a fine example of this. Its glorious initial City Hall, constructed in the late 19th century when Winnipeg was a boomtown, the laying of its cornerstone was a momentous occasion and a public holiday. Looking at the old building, it’s easy to see why Winnipeggers were so proud of it. It was a striking Victorian presence over the city. But, by the 1960s, it was antiquated and, like Boston, the ‘Peg choose to replace its City Hall with a new brutalist design.

Winnipeg is a fine example of this. Its glorious initial City Hall, constructed in the late 19th century when Winnipeg was a boomtown, the laying of its cornerstone was a momentous occasion and a public holiday. Looking at the old building, it’s easy to see why Winnipeggers were so proud of it. It was a striking Victorian presence over the city. But, by the 1960s, it was antiquated and, like Boston, the ‘Peg choose to replace its City Hall with a new brutalist design.

However, unlike Boston, Winnipeg’s brutalist City Hall at least has greenspace around it. Interestingly, the introduction of greenery and foliage around brutalist architecture can go a long way to normalising it and reducing its imposition on the landscape. This is, I would think, why brutalist architecture on university campuses, as ugly as it is, doesn’t impose in the same way that Government Center does. Government Center is devoid of green space, there isn’t a single one anywhere on the massive, sprawling development.

What Government Center replaced is Scollay Square, which was created officially in 1838, though the name dates back to the end of the 18th century; it was named for William Scollay, a local businessman. Scollay Square was the centre of downtown Boston throughout its existence. The problem was that by the Second World War, Scollay Square was getting seedy. One of its centrepieces was the Howard Theatre, and by this point, it was starting to slide downscale and attract a sleezy clientèle, mostly sailors on shore leave and, oh heavens!, students. Scollay Square was on the decline. And when the Howard was raided by the city’s vice squad in 1953 and shutdown due to a burlesque show, the writing was on the wall. The Howard eventually burned down in 1961. By the 1950s, Boston city officials were looking around for excuses to tear apart Scollay Square. The area was becoming home to too many flophouses and Boston’s rough waterfront had migrated too far inland. The Howard’s destruction by fire became the excuse to step into action, and it was torn down. Over 1,000 buildings were torn down and over 20,000 residents, most of whom were low income, were displaced.

In many ways, Boston is no different than any other North American (or, for that matter, European) city in the 1960s, undergoing urban redevelopment. Montréal also underwent massive redevelopment in the 1960s and 70s, as a trip through the downtown core shows today. Place-des-Arts, Place Desjardins, Place Ville-Marie, the Palais de Justice and the Palais de Congrès all date from this period. It’s not even the scale of Government Center that sets it apart from other redevelopment. No, it’s simply the massive failure of it, and its horrid imposition on the landscape of downtown Boston. Certainly, breaking up the monotony of concrete and red brick with trees, grass, and other such things would help. But, at the end of the day, as ugly as brutalist architecture is elsewhere, nothing can quite touch the size and grandeur of the buildings in Government Center. Walking up Staniford Street, it’s impossible not to be overwhelmed (or maybe the proper term is underwhelmed) by the Government Service Center.

Boston’s mayor, Thomas Mennino, has mused several times in recent years about doing away with at least City Hall and re-locating to South Boston. Not surprisingly, this was met with controversy, as a group called “Citizens for City Hall,” professing to love the building, threatened all kinds of hellfire and damnation should Mennino think about destroying it. Fortunately for them, the recession got in the mayor’s plans. Citizens City Hall sought to have the location designated as a landmark, and also noted that re-locating the seat of city government to Southie, as Mennino planned, would also lead to the dislocation of thousands of residents (again, just as when Government Center was built). At any rate, by 2011, cooler heads prevailed and a new group, “Friends of City Hall” sought to improve the present location and do something to make both City Hall and the Plaza more user friendly. Part of this work will begin this summer, when the MBTA shuts down the Government Center T station to remodel it. Hopefully something can be done to improve Government Center as a whole, not just City Hall and its Plaza, to make this abomination more user-friendly and more aesthetically appealing.

UPDATE: From personal friend and Tweep, John P. Fahey. who grew up in New Haven, CT: Agreed, Government Center suffers in comparison with the architecture in the surrounding area. Urban Renewal was a hot button topic in the 1960s. The idea was to sweep out the old neighborhoods and replace them with new buildings. New Haven did the exact same thing in the 1960s as part of the Model Cities initiative. It knocked down a narrow swathe of a neighborhood that ran from where I-91 starts about 3 miles to Route 34. The City put up an ugly Coliseum that has since been knocked down. When I was a kid I used to ask my mother when they were going to finish it because it never looked complete. New Haven ran out of Urban Renewal money and thus there is this long narrow strip of land extending from the center of New Haven that resembles Dresden after the fire bombing. There was enough Model Cities money to knock down the old neighborhood but not enough to put up the new buildings. If the New Haven Veterans Memorial Coliseum was an example of the type of the architecture that the Elm City would have received, then maybe it was lucky.

UPDATE: From personal friend and Tweep, John P. Fahey. who grew up in New Haven, CT: Agreed, Government Center suffers in comparison with the architecture in the surrounding area. Urban Renewal was a hot button topic in the 1960s. The idea was to sweep out the old neighborhoods and replace them with new buildings. New Haven did the exact same thing in the 1960s as part of the Model Cities initiative. It knocked down a narrow swathe of a neighborhood that ran from where I-91 starts about 3 miles to Route 34. The City put up an ugly Coliseum that has since been knocked down. When I was a kid I used to ask my mother when they were going to finish it because it never looked complete. New Haven ran out of Urban Renewal money and thus there is this long narrow strip of land extending from the center of New Haven that resembles Dresden after the fire bombing. There was enough Model Cities money to knock down the old neighborhood but not enough to put up the new buildings. If the New Haven Veterans Memorial Coliseum was an example of the type of the architecture that the Elm City would have received, then maybe it was lucky.

Canada and the North American Triangle

January 5, 2013 § 3 Comments

Twice in the past few weeks, I have been caught up in discussions about the role of the monarchy in Canada with Americans. These discussions rather astounded me, I have to say. In all my years, I have never really thought all that much about the role of the Queen and her representatives in Canada. Sure, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II is the head of state in Canada (as well as everywhere else in the Commonwealth), but her actual role in Canadian politics is close to nil. Governors-General have been little more than figureheads, responding to the whims of Prime Ministers since the 19th century, not the Queen.

Twice in the past few weeks, I have been caught up in discussions about the role of the monarchy in Canada with Americans. These discussions rather astounded me, I have to say. In all my years, I have never really thought all that much about the role of the Queen and her representatives in Canada. Sure, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II is the head of state in Canada (as well as everywhere else in the Commonwealth), but her actual role in Canadian politics is close to nil. Governors-General have been little more than figureheads, responding to the whims of Prime Ministers since the 19th century, not the Queen.

For my American interlocutors, however, the Queen was a big deal for Canada. They’ve all spent a fair amount of time north of the 49th parallel, and they’re all insightful people. The argument goes something like this: Canada has been prohibited from achieving a full sense of independence of its own because of the on-going association with the former colonial parent through the person of the Queen. Because Canada is not completely sovereign, it cannot be a fully independent nation. It will always be beholden to the United Kingdom. To a person, they all argued that Canadians (at least Anglo Canadians) are very British, in all manners, from our dry sense of humour to our stiff upper lips, and even down to our accents. I was dumbfounded.

I argued that the Queen means very little to Canadians. Aside from the hardcore monarchists, she’s just this grandmotherly woman who pops up on TV now and then. I pointed out that Americans are actually more obsessed with the royal family than Canadians, as evidenced by the marriage of Prince Receding Hairline to whatshername last summer. Sure, the Queen is on our money, but how is that different from Washington and Lincoln being on American money? And certainly Washington has reached the status of a monarchal icon in the USA by now. I argued that, despite the fact that the Queen is the head of state, the Prime Minister is the one who wields power, and quite a lot of it. The Prime Minister decides when elections are to be held, what the policies of government are, etc. In short, sovereignty lies in the Canadian people as expressed through our elected representatives and the Prime Minister; the Queen has nothing to do with this.

But then one of them brought up Prime Minister Harper’s underhanded attempt in 2010 to avoid an election by asking Governor General Michaëlle Jean to prorogue Parliament. He argued that we had an unelected representative of the Queen deciding the fate of the Canadian government. Good point, I conceded, but, the Governor General in 2010 acted in accordance with established constitutional law in Canada and the entire Commonwealth; she acceded to the wishes of the Prime Minister. This wasn’t good enough, the fact remained that the Governor General is unelected. Full stop. And this is proof of Canada’s lack of full sovereignty.

Now I certainly do not buy into the argument that Canada was born on 1 July 1867. As far as I’m concerned the date that we chose to celebrate the birth of our nation is entirely arbitrary and artificial. I have also argued on this blog that Canadian independence has been achieved piecemeal. From the granting of responsible government in 1848 to the patriation of our Constitution in 1982, Canada has inched towards independence. I’d go so far as to argue that in many ways, 1982 is the true date of Canadian independence, as finally our Constitution was an Act of our own Parliament. I certainly do not buy the argument that Canada is doomed because the nation wasn’t born in violence and a war of independence like our American neighbours.

Now I certainly do not buy into the argument that Canada was born on 1 July 1867. As far as I’m concerned the date that we chose to celebrate the birth of our nation is entirely arbitrary and artificial. I have also argued on this blog that Canadian independence has been achieved piecemeal. From the granting of responsible government in 1848 to the patriation of our Constitution in 1982, Canada has inched towards independence. I’d go so far as to argue that in many ways, 1982 is the true date of Canadian independence, as finally our Constitution was an Act of our own Parliament. I certainly do not buy the argument that Canada is doomed because the nation wasn’t born in violence and a war of independence like our American neighbours.

There is also the argument that Canadian unity can never be, due to the fact that upwards of 40% of the population of the second largest province (at any given time) wish to separate from the nation. And, for this reason, Canada is an artificial nation. I think this is a simplistic, and even stupid, argument. It assumes that all nations were born of the nationalist movements that swept across the world from the early 19th to the late 20th centuries. The continued existence of massive multi-ethnic nations such as Russia and China bely this. So, too, does the on-going persistence of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, despite the continued threat of the Scots nationalist movement. Instead, I argue, Canada is successful precisely because it is not a national nation, it is post-national and can house more than a single nation. Indeed, this is what makes Canada not just bi-cultural, but multi-cultural, as we learned in the 1960s, whatever government policies of the day might be.

So I’ve been left stewing over the role of the monarchy in Canada, thanks to my American interlocutors. I’ve also been stewing over different conceptions of democracy. Britain is the modern birthplace of democracy. It is where the people slowly gained control over their nation from the monarchy. At one point, the House of Commons was filled with men hand-picked by the king and his minions, true. But by the 19th century, this was no longer the case. In the UK, the Queen is little more than a figurehead, just like in Canada. But, of course, Elizabeth is English, she’s not Canadian. Thus, she is a foreign queen, according to my American friends. But it’s not that simple. That is an American argument. American democracy works very differently than British or Canadian democracy. And notions of what democracy mean differ as well.

To wit, a few weeks months ago in the Boston Globe, the resident conservative columnist, Jeff Jacoby, was making the argument that the best way to determine whether or not gays and lesbians should be granted rights was through referenda. Only by giving voice to the majority could we determine whether or not a minority should be granted civil rights. That, concluded Jacoby, is how democracy works. To my Canadian mindset, this idea was shocking and appalling. Pierre Trudeau once opined something along the lines that the best determinant of a free and open society is how that society protects its minorities. In short, the rights of minorities should never be left up to majorities. That is what democracy is.

And maybe that’s what this argument boils down to: Canadians and Americans have very different ideas of what democracy is. And for that reason, whilst my American conversants were appalled that Canada would have an unelected, foreign queen, I, a Canadian, could care less. The Queen has no real impact on Canadian life and politics. Her “representative” in Canada, the Governor General, is appointed by and serves at the pleasure of the Prime Minister. And the Governor General has, since 1848, deferred to the wishes of the Canadian Prime Minister. Canada is no less a sovereign nation for this.

And Canada’s inferiority complex has nothing to do with this relationship to the UK, it has everything to do with being the junior partner in North America with the United States and Mexico. Canada is the smallest of the three countries in terms of population, and ranks only slightly higher than Mexico in terms of the size of its economy. The only way in which the colonial relationship with the UK actually does matter is in the sense that Canada has never had the chance to fully stand on its own. It WAS a British colony. And today, it is by and large an American colony. I mean this in terms of the economy, Americans own more of Canada’s economy than Canadians themselves do. And we currently have a governing party, the Conservative Party of Canada, that acts like a branch plant of the American Republican Party.

On Canadian Anti-Americanism

December 18, 2012 § 7 Comments

Sometimes there are few things as depressing as Canadian anti-Americanism. We Canadians are a smug lot, we think we’re smarter, more cosmopolitan, less racist, less sexist, more everything that’s good, less everything that’s bad than Americans. And yet we’re obsessed with Americans. For many of us, our self-identity as a nation is simple: we’re not American. Years ago, even the Canadian Football League fell for this with an ad that asked “WHAT’S THE DEFINITION OF CANADIAN?!? NOT AMERICAN!!!” Yeah, great, thanks for that. I find few things as sad, pathetic, and limiting as we Canadians identifying ourselves in the negative, as in NOT American, NOT British, NOT French.

But it appears that this means of self-definition still appeals to and obsesses too many of my fellow citizens. And this leads to this sad anti-Americanism. The kind that leads Canadians to proudly declare we live in a paradise of non-existant crime, racism, homophobia, etc. And sometimes, it leads to leftist Americans fetishising Canada. Think, for example, of Michael Moore’s fatuous claim in Bowling for Columbine that Canadians don’t lock their doors at night because there’s no crime. I have never, ever, ever left my door unlocked living in Vancouver, Ottawa, and Montréal. Not once. Ever. You think I’m nuts?!?

Canadian anti-Americanism is quite the phenomenon in social media right now. All kinds of Canadians lecturing, hectoring, and badgering Americans (not that they’re paying attention) about guns in the wake of the Newtown massacre (and let’s not forget the mall shooting in Oregon last week) (if you’d really like to depress yourself about mass shootings in the United States over the past thirty years, I have this for you). The script of this particular anti-Americanism is consistent: “You Americans are dumb. You have guns. And you shoot each other and yourselves with them. We Canadians are smart. We don’t shoot ourselves and each other.” And so and so forth. To that, my fellow Canadians, I will remind you of the rash of shootings in Toronto last summer. As for mass shootings, I present École Polytechnique; Concordia University; Taber, AB; Dawson College. You want a closer look at mass shootings in Canada? Go here. But this kind of anti-Americanism is predictable. But it’s not like Americans aren’t upset and distressed by these goings-on. It’s not like Americans aren’t trying to have this very same discussion.

But there’s also the more prosaic kind of anti-Americanism. Since I re-located to Boston this summer, I’ve had a few choice comments directed my way on Twitter and in real life. Comments like “I could NEVER live in the States, it’s so violent,” “Ha! Better get a gun!” and “Americans are dumb” (yes, seriously), and so on and so forth. A couple of weeks ago on Twitter, one numbskull went crazy on me in response to a tweet about the subtle difference I have noticed between the two nations: Canadians have social programmes, Americans have entitlements. This now-former tweep went on a tirade about Americans and war, suggesting that the American entry into the Second World War had nothing to do with the Allies winning the war. But it got better. Apparently the only thing Americans can do is fight, they can’t do diplomacy, and they can’t innovate unless it’s war. Cars, electricity, nope, none of that comes from the United States. Certainly, this kind of irrational anti-Americanism is not the norm in Canada, but it is still symptomatic of the larger problem.

I don’t see how this kind of irrational anti-Americanism can square with our self-image as more erudite, more intelligent, etc. than Americans. For that matter, I can’t see why this comparison even exists in the first place. I am Canadian. Full stop. I am not not-American. I don’t care what Americans are or do. That’s for Americans to decide. As Canadians, we need to get over our inferiority complex.

The Strange Anglo Fascination with Québécois Anti-Semitism

December 13, 2012 § Leave a comment

I am a reader. I read pretty much anything, fiction and non-fiction. As I have argued for approximately forever, reading, and especially, literature, is what keeps me sane. So I read. It’s also the end of the semester, so what I read devolves in many ways from lofty literature to murder-mysteries. I would argue, though, that a good murder-mystery is full of the basic questions of humanity, right down to the endless push/pull of good v. evil. I came to this conclusion when someone once tried to convince me that Dostoyevsky’s Crime And Punishment was, at the core, a murder-mystery.

So, it is that I came to find myself reading the third in John Farrow’s so-far excellent series of murder mysteries set in my home town, Montréal, and featuring the crusty old detective, Émile Cinq-Mars. The third novel, however, centres around Cinq-Mars’ early career in the late 60s/early 70s. And Farrow, who is really the esteemed Canadian novelist, Trevor Ferguson, took the opportunity to write an epic, historical novel. It’s also massively overambitious and falls under its own weight oftentimes in the first half of the book. The novel opens on the night of the Richard Riot in Montréal, 17 March 1955, with the theft of the Cartier Dagger, a relic of Jacques Cartier’s arrival at Hochelaga in the 16th century. The dagger, made of stone and gifted to Cartier by Donnacona, the chief of Stadacona, which is today’s Québec City, has been central to the development of Canada. It has ended up in the hands of Samuel de Champlain, Étienne Brulé, Paul de Chomedy, sieur de Maisonneuve, Dollard des Ormeux, Médard Chouart des Groselliers, Pierre Esprit Radisson, and so on. But it has ended up in the hands of the Sun Life Assurance Company, the very simple of les maudits Anglais in mid-20th century Montréal. Worse for the québécois, Sun Life has lent it to that mandarin of ‘les maudits anglais,” Clarence Campbell, president of the National Hockey League, and the man responsible for the lengthy suspension to Maurice “The Rocket” Richard. Clearly, Farrow subscribes to the theory that the Quiet Revolution really began in March 1955 (I do not agree with this one bit, thank you very much).

Farrow then takes us through the history of the dagger, from Cartier until it ends up in the hands of Campbell, to its theft on St. Patrick’s Day 1955. And from there, we move through the next sixteen years, through the Quiet Revolution, Trudeaumania, and the FLQ, as Cinq-Mars finally solves the mystery of the theft of the Cartier Dagger in 1971 (which was also the year that an unknown goalie came out of nowhere to backstop the Habs to the Stanley Cup).

All throughout the story, Farrow, in true Anglo-Montréal style, is obsessed with franco-québécois anti-semitism. This is especially the case from the late 19th century onwards. We are brought into the shadowy underworld of the Order of Jacques Cartier, a secret society hell-bent on defending French, Catholic Québec against les Anglais and the Jews. Characters real and fictive are in the Order, including legendary Montréal Mayor Camillien Houde, and Camille Laurin, the father of Bill 101, and others. And then there’s the Nazi on the run after the Second World War, Jacques Dugé de Bernonville. We also meet Pierre Elliott Trudeau and his nemesis, René Levésque.

Outed as anti-semites are the usual characters: Maurice Duplessis, Abbé Lionel Groulx, Houde, Laurin, and, obviously, de Bernonville. Also, Henri Bourassa and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine. And so on and so forth. And, ok, fair enough, they WERE anti-semites (though I’m not sure you can call Bourassa and Lafontaine that). Québec, and Montréal in particular, was the home of Adrien Arcand, the self-proclaimed fuhrer of Canada. These are disgusting, dirty men.

But all throughout the novel, only French Canadian anti-semitism matters. This reminds me of a listserv of policy wonks, academics, and journalists I’ve been a member of for a decade-and-a-half. Years ago, we had one member who liked to rail against the sovereigntists in Québec, accusing them of being vile anti-semites (sometimes he was right). But, whenever evidence of wider Canadian anti-semitism was pointed out, he dismissed it out of hand. In his mind, only the French are anti-semites (to the point where he often pointed to the Affair Dreyfus in late 19th century France as proof the québécois are anti-semites to the core).

I am not suggesting that anti-semitism should not be called out for what it is: racism. It must and should be. But whenever we get this reactionary Anglophone obsession with Franco-québécois anti-semitism, I get uncomfortable. This is a bad case of the pot calling the kettle black. Anti-semitism has been prevalent in Canada since the get go, in both official languages. The first Jew to be elected to public office in the entire British Empire was Ezekiel Hart, elected to the Lower Canadian legislature in 1807. But he was ejected from the House almost immediately upon taking his seat because he was Jewish. The objections to Hart taking his oath of office on the Jewish Bible (which was standard practice in the court system for Jews) were led the Attorney-General, Jonathan Sewell. But the people of Trois-Rivières returned him to office nonetheless. He was again refused his seat. Opposition came from both sides of the linguistic divide in Lower Canada, and you will surely note Sewell is not a French name. Lower Canada, however, was the first jurisdiction in the British Empire to emancipate Jews, in 1833. The leader of the House, and the Parti patriote? Louis-Joseph Papineau.

At any rate, this isn’t a defence of the franco-québécois record on anti-semitism. It’s not good. But it is to point out that Anglo Canada isn’t exactly pristine. Irving Abella and and Harold Troper’s book, None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948 makes that point clear. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s immigration chief, Frederick Blair, made sure that Jews fleeing Nazi Germany weren’t allowed into Canada. Jews had been coming to Canada since the late 19th century, and there, they met an anti-semitic response, whether it was Montréal, Toronto, or Winnipeg. Even one of our great Canadian heroes, Lester Bowles Pearson, Nobel Prize-winner for inventing UN Peacekeepers and Prime Minister from 1965-7, was an anti-semite, at least as a young man before the Second World War.

And anti-semitism has remained a problem in Canada ever since. While anti-semitism is relatively rare in Canada, B’Nai Brith estimates that, in 2010, upwards of 475 incidents of anti-semitism happened in Toronto alone.

So clearly Canadian anti-semitism isn’t a uniquely franco-québécois matter. Indeed, one of the few Anglos to feature in Farrow’s book, Sir Herbert Holt, was himself somewhat of an anti-semite himself. And I am left feeling rather uncomfortable with this strange Anglo Québec fascination with the anti-semitism of francophone québécois, especially when it’s presented out of the context of the late 19th/early 20th centuries. This was a period of pretty much worldwide anti-semitism. It was “in fashion,” so to speak, in the Euro-North American world, from actual pogroms in Russia to the Affaire Dreyfus, to the US and Canada refusing to accept refugees from Nazi Germany thirty years later.