(Not) Commemorating the Irish Famine in Montreal

May 25, 2017 § 6 Comments

The Irish Famine was one of the great humanitarian disasters of the 19th century. A blight upon the potato crop, combined with British malfeasance, brought about a crisis that saw Ireland lose around 25% of its population between 1845 and 1852. One million people died. Another million emigrated. This was the birth of the Irish diaspora as we know it today.

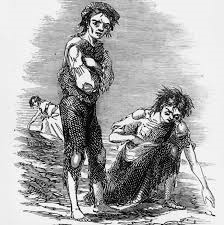

Famine refugees in Ireland (woodcut)

Montreal is one of the great cities of the diaspora, even if most of the Irish world doesn’t know this. Something like 40% of Quebecers have Irish heritage. And the Irish have long been recognized as one of the ‘founding peoples’ of the city. The flag of the Ville de Montréal features the flowers of each of the ‘founding peoples’ of the city: the French, English, Scots, and Irish, and a cross of St. George. The landscape of the city is littered with remembrances of the Irish, from rue Shamrock by Marché Jean-Talon in the North End (where the old Shamrocks Lacrosse Club stadium was) to Loyola College (now part of Concordia University) and rue Dublin in Pointe-Saint-Charles.

The flag of the Ville de Montréal

During the Famine, the city was inundated with refugees. Even with a quarantine station on Grosse-Île, up the St. Lawrence River near Quebec, the sick and the dying still made it downriver to Montreal. They ended up in fever shacks on Pointe-Saint-Charles, just across the Lachine Canal from Griffintown. Upwards of 6,000 of them were dumped in a mass grave that went largely unmarked and forgotten until 1859, when a bunch of Irish construction workers, building the Victoria Bridge, unearthed them. The workers erected a huge black rock to mark the grave.

The Black Rock

Don Pidgeon was the long-time historian of the United Irish Societies of Montreal, until he died last year. He liked to argue that the rock was the birth place of Irish Montreal. It was largely due to him that the Black Rock has been preserved and cared for. For as long as I can remember, the Irish community of Montreal sought to create a proper memorial park to commemorate the Famine dead. The Black Rock currently sits on an island in the middle of Bridge St., the Montreal approach to the Victoria Bridge, near where Goose Village once stood. During rush hour, Bridge St. is congested and car-heavy. It is no way to commemorate the dead.

Montreal is the only major diaspora city that lacks a Famine Memorial. This is shocking and so very typically Montreal in many ways. Montreal exists as it does today in large part due to the inundation of the Irish in the early 19th century. This is true both demographically, but also infrastructurally. The Irish built the bulk of the city’s 19th century infrastructure: the Lachine Canal, the railways, Victoria Bridge, the buildings and factories, and their muscle dredged the Montreal harbour, expanding it for bigger and bigger cargo ships. They were also a key constituency of the industrial working classes in the 19th century. They were present at the beginnings of the Canadian industrial revolution in Griffintown, and they helped power the city into the industrial centre of Canada. The influx of Irish also meant that for a brief period in the second half of the 19th century, English-speaking people were the majority of the population in the city. And while the Famine is not the means by which all the Montreal Irish got there, it is a central story to the Irish in Montreal.

This is true of both the Famine refugees, but also the Irish community that was already there. St. Patrick’s Basilica opened its doors on 17 March 1847, at the very start of the worst year of the Famine, Black ’47. But that the Irish could construct a big, handsome church on the side of Beaver Hall Hill in 1847 also signifies the depth of the roots of the Irish in Montreal. Even as early as the 1820s, there was a firmly ensconced Irish population in the city. But when the flood gates opened and the refugees began streaming in later that spring of 1847, the Montreal Irish got to work. They donated large sums of money to the care of their brethren, they volunteered to work in the fever sheds, they helped the survivors set up in Montreal (it is worth noting that the same was true of the rest of the city’s population, whatever its ethnic background).

In short, the years of the Irish Famine were central to the development of Irish Montreal. And perhaps more to the point, following the Famine, Irish emigration to Montreal (and Canada as a whole), dried up. Thus, in many ways, the Irish of Montreal were able to integrate and assimilate into the wider city. They shared a language with the economically dominant group, a religion with the numerically dominant. And the growing stability of the population aided in this process. In short, in some ways, the Irish experience was not as fraught in Montreal as it was in other diasporic locations, where nativism and anti-Irish sentiment held sway.

The Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation kicked into gear last year, with its plan to build a proper memorial. The goal, according to the Foundation’s website, is to create a memorial park that would include playing fields for Irish sports, a theatre, and a museum on the site. This park would be strategically located, and presumably would be connected to the Lachine Canal National Historic Site nearby, which is itself a heavily-used park.

The Foundation appears to have had all of its ducks lined up, with support from the Irish community, corporate Montreal, and the Mayor’s office. The Irish Embassy in Ottawa was also supportive, willing to kick in some money (as it had with the Toronto Famine Memorial).

And then, a few weeks ago, the land that it proposed to acquire for the park was sold by the Canada Lands Company (a Crown corporation that deals with public land) to Hydro-Québec, which wants to build a sub-station there, ironically due to the massive redevelopment of Griffintown. And while there is allegedly a clause in the sale requiring Hydro-Québec to build a monument to the Famine dead, that’s cold comfort. Who is going to go look at a monument along a busy road next to an sub-station?

And so, at least for now, the dream of a proper memorial to the Famine refugees in Montreal is dead. This year marks the 375th anniversary of the founding of Montreal, but it is also the 160th anniversary of Black ’47.

I have a hard time believing that something like this would happen in any other city. A project with community, corporate and political support got derailed by two Crown corporations. I don’t quite understand how this could have come as a surprise, as in, how did the Foundation not know that Canada Lands was negotiation with Hydro-Québec? Then again, this is Montreal, so that is also entirely within the realm of possibility. And this entire affair is so typically Montreal.

Tagged: (not)commemorating, Commemoration, griffintown, irish diaspora, irish famine, memory, montréal, Pointe-Saint-Charles, politics, the black rock

[…] Remember how last week I mentioned the trouble that the United Irish Societies of Montreal was having in establishing a memorial for the victims of the Irish famine? Mathew Barlow examines this subject in more detail, and explores why Montreal is the only major Iris… […]

[…] week, the news out of Montreal was that the piece of land the Irish Memorial Foundation sought to create a proper memorial of the […]

Sigh.

I’ve a slight connection to the Irish of Montreal: my Irish paternal great-grandmother’s two sisters landed there in the years following the Hunger. They hoofed it down to Boston to meet up with their sister. The story goes that they each had only one pair of shoes, and so walked mostly barefoot through the winter and New Hampshire, so as not to wear the shoes out.

There are many such legends of the Irish hoofing it from Canadian ports of call South to Boston, NYC, etc., though I tend not to believe the walking across the Appalachians barefoot in winter. That’s how one gets frostbite, and starves to death.

And it’s possibly been mythologized in my family, too; after all, my father’s account of another relative (who in fact probably isn’t one), Capt. Blood, departed significantly from the truth.

The Irish, telling tales that veer from the truth? I don’t believe it. 😉