What the Hell?

August 22, 2016 § 4 Comments

UPDATE: I thought this rhetoric about the Prime Minister couldn’t get worse. Turns out I was wrong; it can. And it has been for some time.

As every Canadian knows, the Tragically Hip held their last ever concert in their hometown of Kingston, ON, on Saturday night. Something like 11 million TV sets in Canada were tuned to the gig, broadcast coast-to-coast-to-coast on the CBC. For those of you who don’t know, that’s about 1/3 of the population of the entire country. I haven’t seen numbers for how many of us watched on YouTube, as the CBC streamed the show worldwide. Social media was full of pics, remembrances, stories about The Hip, a quintessentially Canadian band. If you’re not Canadian, I simply cannot explain the importance of this band to most Canadians. It’s something non-quantifiable.

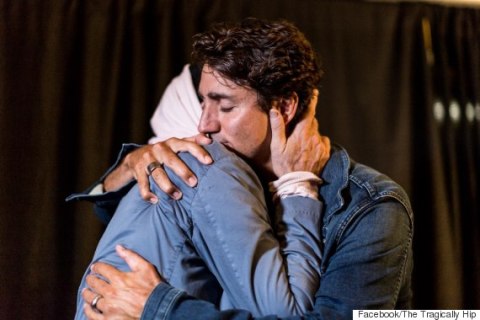

The Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, was there in Kingston, one of the lucky 7,000 people inside the unfortunately named K-Rock Centre. Gord Downie, the frontman who is dying of cancer, gave the PM a couple of shoutouts, particularly insofar as Canada’s abysmal record vis-à-vis our First Nations. In the aftermath, a picture of Downie and Trudeau sharing a hug made the rounds on social media. It’s a particularly touching image, and it shows Downie’s frailty.

But then Twitter happened. A series of tweets from bitter, and mostly anonymous, Canadian conservatives attacked Trudeau for a variety of reasons, most of them just a sad bit of bitterness. For example:

https://twitter.com/politicsinmemes/status/767155353746153473

or,

These were relatively mild, however. Others wished personal ill on the Prime Minister. But the worst tweet I saw was this one:

https://twitter.com/FACLC/status/767174725747433473

What kind of person says something like this? What has happened to the Canadian conservative movement that this can even happen? FACLC’s tweet is simply the most egregious example that came through my timeline in the past few days.

While I can certainly understand a deep-seated dislike, even hatred, for a Prime Minister (i.e.: Stephen Harper), I do not know anyone who tweeted vileness like this, who wished personal ill on the Prime Minister of Canada FACLC and anyone who supports such viciousness should be deeply ashamed of themselves. So should anyone who posted such vileness in the first place. This is not Canada, this is not who we are.

The Five Foot Assassin

March 24, 2016 § Leave a comment

Phife Dawg, also known as Malik Taylor, died a couple of days ago. He was only 45. Phife is a hip hop legend, one of my favourite MCs of all-time. His music as a member of A Tribe Called Quest and his single solo album from 2000 have long been part of the soundtrack of my life. The Five-Foot Assassin was a perfect foil to Q-Tip’s smooth delivery, with his guttural growl and ability to drop a patois. He also wrote wicked rhymes, tougher and more menacing than Tip.

Tip was the unquestioned leader of Tribe. And eventually, egos got in the way of old friends. Phife always said that he felt especially excluded because both Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad, the DJ, had both converted to Islam and he had not. And he was largely absent from the 1996 album, Beats, Rhymes, and Life as Tip’s cousin, Consequence, was featured (why, I have no idea, he couldn’t hold a flame to Phife’s abilities). I remember buying Midnight Marauders in the fall of 1993 at Zulu Records on West 4th Avenue in Vancouver. I was with my friend, Tanya. It was one of the first CDs I ever bought. I still have it. The fall of 1993 was when I moved back to Vancouver from Ottawa, transferring to the University of British Columbia. I lived in the Mötördöme, with three other guys I didn’t know all that well. I worked with Steve at the Cactus Club (or the Carcass Club, as we called it) on Robson St. We also lived with Skippy, who had a law degree, but preferred to play in punk bands, and J., who was also in a punk band. That was the fall when I took the #22 bus to work on weekend mornings, I rode with Chi-Pig, legendary front-man of SNFU. Punk was the regular soundtrack at the Mötördöme; Fugazi and Jesus Lizard were our favourites. But we also played a lot of Fishbone and Faith No More. And when we were in reflective moods, we dropped some Tom Waits on. Skip, Steve, and J. were not fans of hip hop. But I insisted on playing Midnight Marauders as well. And when me and my main man Mike rode around Vancouver and its environs in the Mikemobile, a 1982 Mercury Lynx, Midnight Marauders was amongst the albums we rotated. I listened to the album on my long bus ride to UBC on the #9 Broadway bus.

Everytime I listen to that album, I am immediately dropped back into Vancouver in 1993. Similarly, their last album, 1998’s The Love Movement came out the year Christine and I moved to Ottawa, so she could begin law school. I had just graduated from Simon Fraser with my MA in History and would soon begin a long run at Public History Inc., which launched me back into academia. I got to Ottawa a month earlier than her. And in a small flat, in a very hot Ottawa summer, I listened to The Love Movement almost obsessively. It’s generally not regarded as Tribe’s best, but Phife’s rhymes, especially on “Find A Way” and “Da Booty,” made the album.

I got backstage at a couple of Tribe shows back in the day. I got to meet them. Phife was unfailingly the nicest, most polite dude you could imagine. He was just a genuinely nice guy. He was always humble, he also seemed kind of surprised he was a big deal.

I am listening to Midnight Marauders right now. Hip hop has lost one of the greatest MCs of all-time. And he was too young to go.

Reflections on Feminism and Class

February 6, 2015 § 2 Comments

I watched The Punk Singer, the documentary about Kathleen Hanna, the frontwoman of the Riot Grrrl band, Bikini Kill, as well as Le Tigre and The Julie Ruin, the other night. Hanna was, essentially, the founder of the Riot Grrrl movement back in 1992; she wrote the Riot Grrrl Manifesto. I’ve always been a fan, and I remember going to Bikini Kill shows back in the day. Hanna would insist the boys move to the back of the crowd and the girls come down to the front. And we listened to her. She was an intimidating presence on a stage. The girls came down front so they could dance and mosh and not get beaten to a pulp by the boys. Early 90s mosh pits were violent places, and they got worse as they got invaded by the jocks after Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and a few other bands went mainstream. Bikini Kill never did, but their shows, as well as those of L7 and Babes in Toyland, still attracted these wider audiences, at least the gigs I went to. Hanna and Bikini Kill were unabashedly feminist. If you didn’t like, you could just fuck off.

Yesterday in class, in a very gender-segregated room (women on the left, men on the right), we had an interesting discussion. We were discussing Delores Hayden’s The Power of Place, about attempts to forge a public history on the landscape of Los Angeles that gives credence to the stories of women and minorities. So. I asked my students if women were a minority. To a person, they all knew that women are not a minority, at least not in demographic terms. Women are the majority; right now in the United States and Canada, around 51% of the population. But. Women are a minority in terms how they are treated in our culture, how they are second-class citizens, essentially. The women in my class all knew this, they were all adamant about it. The men stayed silent, though they nodded approvingly at what the women were saying.

Despite the fact that close to nothing has changed in the mainstream of our culture, that we still live in a rape culture that is designed to keep women de-centred and unbalanced, I was so happy that my students knew what was what in our world, and I was so happy that the men knew to keep their mouth shut.

In The Punk Singer, Lynn Breedlove, a queer feminist writer, singer, and punk, noted that feminism is about the struggle of the sub-altern, about the struggle of the oppressed. And feminism should fight for the oppressed, no matter the fight, be it race, sexuality, or class. And I had this lightning bolt moment. This is why I have always been pro-feminist. I had a prof in undergrad who argued that men cannot be feminists; feminism is a movement for and by women. Men could be allies, in fact, they were welcomed, but it was a women’s movement. Hanna reflects this, she has always worked to create a space and a voice for women, and men were welcome, but in a supporting role. I like that.

I was raised by women, and my mother instilled this pro-feminism in me at a young age (thanks, Ma!). But, feminism (along with punk) helped give me the tools I need to emancipate myself from the oppression of class. From these two movements, I gained a language of emancipation. To recover from being told by my high school guidance counsellor that “People like you don’t go to university,” because I was working-class and poor. Richard Sennett and Jonathan Cobb, in a 1993 book, talk about the ‘hidden injuries of class.” Hidden, yes, but still very real.

Memory and the Screaming Trees.

January 26, 2015 § 4 Comments

Memory works in odd ways. So this course on space, place, landscape & memory. Last Thursday, in addition to that article on Western Mass, we read Doreen Massey’s article “Places and Their Pasts,” from way ‘back in 1995. And, this got me thinking. About music. I’m currently in a hard rock phase, where everything I’m listening to has loud, very loud guitars. And inevitably, when I am in one of these phases, I come back to the Screaming Trees’ 1992 album, “Sweet Oblivion.” My favourite Trees’ song, “Nearly Lost You” is on this album. But, the album as a whole is one of my favourites of all-time. I first bought it on cassette tape, back when it came out in the fall of 1992. I bought it at the Record Runner, a legendary record store on Rideau Street in Ottawa, that closed in January 2006, after 31 years in business due to gentrification and condofication. When I moved back to Vancouver the following spring, 1993, my best friend, Mike, had the album on CD.

We spent a lot of time driving around the Vancouver region that summer and fall, in his 1982 Mercury Lynx, which I had dubbed the Mikemobile. Mike had a Sony Discman, which he plugged into the cassette player of his car to listen to CDs. It was incredibly moody and jumped when the car hit bumps. Nonetheless, “Sweet Oblivion” was in constant rotation that year. There is, however, a difference between the cassette and CD (and now, digital) versions of the album, however. Track 6, “For Celebrations Past” was not on the cassette version. I listened to the cassette version of the album a lot, but I’ve listened to the CD and digital versions of the album even more. I’ve listened to this album hundreds of times, and I’d estimate at least 80% of those plays are either the CD or digital version. And yet, every time I hear “For Celebrations Past,” it feels like a rude interlude into a classic album of my youth, even though I like this song, too.

I find it interesting that my initial memories of this album trump the memories of the version of the album I’ve heard many more times over the years. I’m not sure what to make of this, really. My memories of Ottawa in 1992-3 are not all that happy, though there was the diversion of Montreal and the Habs’ last Stanley Cup victory, but by the time Guy Carbonneau lifted Lord Stanley’s mug that spring, I was back in Vancouver. So it is bizarre, I think that, my initial memories of the album trump the happier ones, back in Vancouver. And yet, listening to the album, as I did last night, doesn’t transport me back the sub-Arctic cold of Ottawa anymore than it puts me back in the passenger seat of the Mikemobile. Unlike a lot of the music of the early 90s, it’s not evocative of that time and place. Maybe because I’ve continued to listen to the album in the years since. Yet, for me, the proper version of the album lacks “For Celebrations Past” and goes straight from the organs and guitars of “Butterfly” into the vicious punk-inflected “The Secret Kind.”

What Steve Earle can teach us about the Annales school of historiography

October 2, 2014 § 4 Comments

I’m teaching a course on Historiography this semester. This week, we’re dealing with the Annales school of history, as a sort of background before we read Marc Bloch’s Strange Defeat. While this book isn’t really an annaliste work, Bloch’s theories of history still impacted his evisceration of his country after the Fall of France in 1940. We’re reading an excerpt from Fernand Braudel’s magnum opus, La Méditerranée et le Monde Méditerranéen à l’Epoque de Philippe II, published in 1949.

In it, Braudel talks about the mountain regions of the Mediterranean world, and argues that the culture and civilisation of the plains didn’t reach into the mountains. The hills, he claims “were the refuge of liberty, democracy, and peasant ‘republics.'” And he mentions bandits. One of my favourite history books of all-time, and one which was massively influential on me as a young scholar, is Eric Hobsbawm’s Social Bandits and Primitive Rebels, which, despite Hobsbawm being primarily thought of as a Marxist, was deeply indebted to the annalistes, and to Braudel in particular.

But, as Braudel goes on and on about the freedom of the mountains, I kept thinking about hillbilly culture, about the Hatfields and the McCoys, about hillbilly culture, and so on. And it occurred to me that the mountains are no longer this mythical place beyond the reach of modern society. The coercive power of the state has caught up to the mountains.

And then I thought of my favourite Steve Earle song, “Copperhead Road.” In this song, Earle sings of three generations of a family who live in the ‘holler’ down Copperhead Road. In the American Civil War era, copperheads were northern Democrats who opposed the Civil War and called upon President Lincoln to immediately come to peace with the Confederacy. Braudel argues that

The mountain dweller is apt to be the laughing stock of the superior inhabitants of the towns and plains. He is suspected, feared, and mocked…The lowland peasant had nothing but sarcasm for the rude fellow from the highlands, and marriages between their families were rare.

At any rate, Earle sings of John Lee Pettimore III, named after his “daddy and his daddy before.” Granddaddy John Lee made moonshine down Copperhead Road. Daddy John Lee ran whiskey in a big black Dodge, which he bought at an auction. Meanwhile, John Lee III is a Vietnam vet growing marijuana in the holler down Copperhead Road. He signs the song in a good ol’ boy twang, and sings of white trash.

Granddaddy John Lee hid out down Copperhead Road, only came to town twice yearly for supplies, and successfully dealt with a “revenue man” from the government. Daddy John Lee was doing alright for himself before he crashed that big, black Dodge and the whiskey he was running burst into flames, killing him, on the weekly trip down to Knoxville. Meanwhile, John Lee III wakes up in the middle of the night with the DEA and its choppers in the air above his land.

In other words, as we move through the 20th century, from Granddaddy in the 1940s to John Lee III in the 1980s, we see the mountains lose their allure and mystique. What was once the badlands is now under the control of the government. In the early 21st century, it is even more so.

Memory and the Music of U2

September 15, 2014 § 2 Comments

[We now return to regular programming here, after a busy summer spent finishing a book manuscript]

So U2 have a new album out, they kind of snuck up on us and dropped “Songs of Innocence” into our inboxes without us paying much attention. Responses to the new album have ranged from ecstatic to boredom, but I’ve been particularly interested in how the album got distributed: Apple paid U2 some king’s ransom to give it to us for free. Pitchfork says that we were subjected to the album without consent, a lame attempt to appropriate the words of the ant-rape movement to an album.

As for me, I’m still not entirely sure what I think of “Songs of Innocence.” I think it’ll ultimately be disposable for me, though it’s certainly better than their output last decade, but not as good as the surprising “No Line on the Horizon” which, obviously was not up to the standard of their heyday in the 80s and 90s. And I’m not sure about Bono’s Vox as he ages, it’s starting to sound too high pitched and thin for my tastes, whereas it used to be so warm and rich.

Anyway. iTunes is now offering U2’s back catalogue on the cheap. I lost most of my U2 cd’s in a basement flood a few years ago, so I took a look. But looking at the album covers, I was struck by the flood of memories that came to me. For a long time, U2 were one of my favourite bands, and “The Joshua Tree” has long been in the Top 3 of my Top 5. But, just how deeply U2’s music is embedded in my memories was surprising. For example, looking at the cover of “The Unforgettable Fire,” I am immediately transported back in time, to two places. First, I’m 11 or 12, in suburban Vancouver, listening to “Pride (In the Name Of Love)” for the first time, on C-FOX, 99.3 in Vancouver. Secondly, I’m on a train to Montreal, from Ottawa, in the fall of 1991, listening to “A Sort of Homecoming” as I head back to my hometown for the first time in a long time.

Anyway. iTunes is now offering U2’s back catalogue on the cheap. I lost most of my U2 cd’s in a basement flood a few years ago, so I took a look. But looking at the album covers, I was struck by the flood of memories that came to me. For a long time, U2 were one of my favourite bands, and “The Joshua Tree” has long been in the Top 3 of my Top 5. But, just how deeply U2’s music is embedded in my memories was surprising. For example, looking at the cover of “The Unforgettable Fire,” I am immediately transported back in time, to two places. First, I’m 11 or 12, in suburban Vancouver, listening to “Pride (In the Name Of Love)” for the first time, on C-FOX, 99.3 in Vancouver. Secondly, I’m on a train to Montreal, from Ottawa, in the fall of 1991, listening to “A Sort of Homecoming” as I head back to my hometown for the first time in a long time.

The cover of “Zooropa” takes me back to the summer of 1993, riding around Vancouver in the MikeMobile, the ubiquitous automobile of my best friend, Mike. That summer, “Zooropa” alternated with the Smashing Pumpkins’ “Siamese Twins” in the cd player, which was a discman plugged into the tape deck of the 1982 Mercury Lynx. US and the Pumpkins were occasionally swapped out for everything from Soundgarden and Fugazi to the Doughboys and Mazzy Star, but those two albums were the core.

The cover of “Zooropa” takes me back to the summer of 1993, riding around Vancouver in the MikeMobile, the ubiquitous automobile of my best friend, Mike. That summer, “Zooropa” alternated with the Smashing Pumpkins’ “Siamese Twins” in the cd player, which was a discman plugged into the tape deck of the 1982 Mercury Lynx. US and the Pumpkins were occasionally swapped out for everything from Soundgarden and Fugazi to the Doughboys and Mazzy Star, but those two albums were the core.

“Boy” takes me back to being a teenager, too, my younger sister, Valerie, was also a big U2 fan back in the day, and she really liked this album, so we’re listening to it on her pink cassette player (why we’re not next door, in my room, listening on my much more powerful stereo, I don’t kn0w). She went on to become obsessed with the Pet Shop Boys’ horrid, evil, and wrong cover of “Where the Streets Have No Name” (and the PSB were generally so brilliant!), to the point where she once played the song 56 times in a row on her pink cassette player, playing, rewinding, and playing the cassette single over and over.

“Boy” takes me back to being a teenager, too, my younger sister, Valerie, was also a big U2 fan back in the day, and she really liked this album, so we’re listening to it on her pink cassette player (why we’re not next door, in my room, listening on my much more powerful stereo, I don’t kn0w). She went on to become obsessed with the Pet Shop Boys’ horrid, evil, and wrong cover of “Where the Streets Have No Name” (and the PSB were generally so brilliant!), to the point where she once played the song 56 times in a row on her pink cassette player, playing, rewinding, and playing the cassette single over and over.

Obviously the soundtrack of our lives (or The Soundtrack Of Our Lives, a brilliant Swedish rock band last decade) is deeply embedded in our memories, much the same way that scents can transport us back in place and time. But I was more than a little surprised how deep U2 is in my mind, how just seeing an album cover can take me back in time across decades, and in place, across thousands upon thousands of kilometres.

The Suburbanisation of Punk and Hip Hop

April 23, 2014 § Leave a comment

Questlove, the drummer and musical director of the hip hop band, The Roots (and frankly, if you don’t know just who in the hell The Roots are by now, I’m not sure there’s any hope for you), is writing a six-part series of essays on hip hop, its past, present, and future at Vulture. Not surprisingly, Questlove makes an eloquent argument in part one about the ubiquity of hip hop culture and the dangers that poses to Black America in the sense that if the powers that be wish to quash it, the ubiquity of it is all-encompassing and a quashing would be similarly so. But he also points out the dangers of the all-encompassing nature of hip hop culture.

I like Questlove’s point about the ubiquity of hip hop culture, which means that it’s no longer visible, it’s just everywhere. He also notes that it’s really the only music form that is seen to have this massive cultural phenomenon attached to it: food, fashion, etc. He says that this applies to pretty much anything black people in America do (he also wonders what the hell “hip hop architecture” is, as do I). But I think this goes beyond black America, such is the power of hip hop and the culture that follows it.

There is a relatively long tradition of white rappers, from 3rd Bass and the Beastie Boys up to Eminem and others, and the vast majority of white rappers have deeply respected the culture. More than that, as a white kid growing up in the suburbs in the late 80s, I was totally into hip hop, as were all my friends. This could get stupid, as when guys I knew pretended that life in Port Moody was akin to Compton, but, still. My point is that hip hop music, fashion, and culture has permeated the wider culture of North America entirely (something I don’t think Questlove would disagree with, but it’s irrelevant to his argument).

The only other form of music that has an ethos and culture that follows it, really, is punk. Punk and hip hop are spiritual brother movements, both arise from dispossessed working class cultures. Both originally emerged in anger (think of the spitting anger of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five in “The Message” or the Sex Pistols in “Anarchy in the UK”) and were heavily political and/or documented life on the downside. But, both also went viral, both exploded out of their original confines and went suburban and affluent.

Punk and hip hop are the two musical forms that informed me as a young man, they continue to do so as I hit middle age. But punk and hip hop are both deeply compromised by sinking into the affluent culture of middle class suburbia. The anger is blunted, the social message is reduced, and it becomes about “bitches and bling,” whether in hip hop (pretty much any song by Jay-Z) or punk (pretty much any song by The Offspring, Avril Lavigne, Blink-182, or any pop-punk band you hear on the radio). And then these counter-culture voices become the culture, and, as Questlove notes, they become invisible in their ubiquity. But more than that, the ethos they bring is divorced from their origins.

Questlove talks about the social contract we all subscribe to. He references three quotes that guide his series (and, I would guess, his life in general). The first comes from 16th century English religious reformer, John Bradford, who upon seeing another prisoner led to the gallows, commented, “There but for the graces of God goes John Bradford.” The second comes from Albert Einstein, “who disparagingly referred to quantum entanglement as ‘spooky action at a distance.'” Finally, Ice Cube, the main lyricist of N.W.A. (yes, there was once a time, kids, when Cube wasn’t a cartoon character), who, in the 1988 track “Gangsta Gangsta,” delivered this gem, “Life ain’t nothing but bitches and money.” Questlove also notes that Cube is talking about a world in which the social contract is frayed, “where everyone aspires to improve themselves and only themselves, thoughts of others be damned. What kind of world does that create?”

And herein lies the rub for me, at least insofar as the wider culture of hip hop and punk and their suburbanisation. If you take the politics and intelligence out of punk and hip hop, you’re left with the anger, and a dangerous form of nihilism. We’re left with Eminem fantasising about killing his wife and his mother. Charming stuff, really.

This is not to say there is no place for bangers in hip hop culture, nor is to say there’s no place for the Buzzcocks (the progenitors of pop-punk in the late 1970s), it just means that this is a many-edged sword.

Slave Narratives and the Carolina Chocolate Drops

March 31, 2014 § 6 Comments

Last night, we were up in Woodstock, VT, to see the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a string band from Durham, North Carolina. The band is comprised of three African-Americans and fronted by Rhiannon Giddens, who is of mixed white, black, and aboriginal descent, they play a mixture of traditional and modern folk/roots instruments. They’ve revived a number of songs from the slave era in the Deep South, most of which, according to Giddens, were set down in the 1850s, just before the onset of the Civil War. Most of these, however, come without lyrics, for perhaps obvious reasons. The band were incredibly talkative on the stage last night, which created an incredible community vibe inside this small theatre in small-town Vermont. Both Giddens and band mate Hubby Jenkins kept up a running monologue with the crowd, telling us about their songs, how they came to perform them, write them, play them, their traditional instruments, and so on.

Before one song, Giddens told us about her explorations of American history, specifically African-American history, and about a book she read that collated slave narratives, and analysed them collectively, as opposed to the usual individuated approach to slave narratives. However, Giddens also noted one story that stuck out for her, about a slave woman named Julie at the tail end of the Civil War, as the Union Army was coming over the crest of the hill towards the plantation that Julie lived on. Julie is standing with her Mistress, watching them approach in the song, “Julie.”

This video was shot last night, by someone sitting close by us, though I don’t know who shot it, I didn’t see it happening. This is one powerful song, and it got me thinking. I’m teaching the Civil War right now in my US History class, and as I cast about for sources I am intrigued by slavery apologists, then and now, who argue that the slaves were happy. But even more striking are the stories about slave owners who were shocked to their core when the war ended and their slaves took their leave quickly, looking to explore their freedom.

It seems that the slave owners had really convinced themselves that they and their slaves were “friends” and that their slaves loved them. That arrogance seems astounding to me in the early 21st century. But this song last night powerfully brought the story right back around.

When Selling Out Isn’t Selling Out

January 21, 2014 § 2 Comments

I was sitting on my couch watching football on Sunday and a Nike ad came on. The music was familiar. Then it hit me. It was one of my favourite bands, the Montrealers Suuns. It was their track “2020,” the second song on last year’s excellent album, Images du futur. I was a little stunned. Suuns are, for the most part, pretty obscure, even for a Montréal band, many of whom gained attention just due to the simple fact that they were from the same city as Arcade Fire.

I was a little stunned also because Suuns had sold their music to Nike, a multinational corporation, for advertising. Then I realised the massive generational difference at work here. When I was in my 20s, I would be sickened and appalled at any of my favourite alt.rock banks “selling out” to the adverstising industry. Nirvana wouldn’t have done this. Smashing Pumpkins wouldn’t have done this. But the Dandy Warhols did. In 2001, their track “Bohemian Like You” was used in a Vodafone ad. But, that was easy to discount, the Dandys never attempted to claim any alt.rock or indie rock purity. Life carried on.

But the Black Lips did the same thing with T-Mobile. I wasn’t sure what to think about this one, either.

Earlier this weekend, I was having a conversation with a friend on Facebook about the band Neutral Milk Hotel, and she was commenting how she wished music could still be as honest as this band was. We were also talking about the band makes us nostalgic for the 90s.

But still, it’s one thing for M.I.A. to sell her song to Nissan for a car ad, it’s another thing for Suuns to do it. But, of course, the times they are a-changing. For Suuns to sell their song to Nike only works to increase their exposure, to increase record sales. In her brilliant The Gentrification of the Mind, Sarah Schulman talks about this process. She cut her teeth as an artist on the fringe in New York City in the 80s. But today, she notes, artists are all tied into the matrix. For them, it’s not selling out, it’s just the way it is. Skrillex sells his music. So if The Black Lips and Suuns do so, does it make a difference?

I’m sure if I asked my nieces and nephews what they’d think if one of their favourite bands had sold their music for an ad, they’d shrug their shoulders and think I was out of touch. And so, I guess so. Bully for Suuns for selling “2020.”