Irish Slums

December 5, 2013 § 4 Comments

Last month, I met Michael Patrick MacDonald at an Irish Studies conference in Rhode Island. He was the keynote speaker. I didn’t know much about him beforehand, other than he wrote All Souls about growing up in South Boston in the 70s and 80s. I knew All Souls was a story about heartbreak, drugs, and the devastation suffered by his family. But MacDonald’s talk was one of the best I’d ever heard, he spoke of Whitey Bulger, drugs, Southie, his work in non-violence and intervention, and he talked about gentrification. He was eloquent and fierce at the same time. He is, of course, an ageing punk. He was also pretty cool to talk to over beers in the hotel bar later that night.

I finally got around to reading All Souls last week. I’m glad I did. I was stunned that MacDonald and his siblings could survive what they’ve survived: three of their brothers dead due to gangs, drugs, and violence. One of their sisters permanently damaged by a traumatic brain injury brought about due to drugs. And another brother falsely accused of murder. It was a heartbreaking read, at least to a point. I know how the story ends, obviously.

It was also interesting to read another version of Southie than the one in the mainstream here in Boston. The mainstream is that Southie was an Irish white trash ghetto, run by Whitey Bulger, terrorised by Whitey Bulger, but all those Irish were racists, as evidenced by the busing crisis in 1974. And while MacDonald tried to revise that narrative, both in his talk and in All Souls, pertaining to the busing crisis, it is hard to argue that racism wasn’t the underlying cause of the explosion of protesting and violence. But, MacDonald also offers both a personal and a sociological view of how Southie was terrorised and victimised by Bulger (and his protectors in the FBI and the Massachusetts State Senate). And, today, he talks about gentrification in a way that most mainstream commentators do not (something I’ve railed about in my extended series on Pointe-Saint-Charles, Montréal, his blog, Pt. 1, Pt. 2, Pt. 3, Pt. 4, and Pt. 5).

But something else also struck me in reading MacDonald’s take on Southie. I found that he echoed many of the oldtimers I’ve talked to in Griffintown and the Pointe in Montréal about their experiences growing up. Griff and the Pointe were the Montréal variant of Southie, downtrodden, desperately poor Irish neighbourhoods. And yet, there is humour to be found in the chaos and poverty, and there is something to be nostalgic for in looking back.

MacDonald writes:

I didn’t know if I loved or hated this place. All those beautiful dreams and nightmares of my life were competing in the narrow littered streets of Old Colony Project. Over there, on my old front stoop at 8 Patterson Way, were the eccentric mothers, throwing their arms around and telling wild stories. Standing on the corners were the natural born comedians making everyone laugh. Then there were the teenagers wearing their flashy clothes, their ‘pimp’ gear, as we called it. And little kids running in packs, having the time of their lives in a world that was all theirs.

This echoes something journalist Sharon Doyle Driedger wrote of Griffintown, where she grew up:

Griffintown had the atmosphere of an old black-and-white movie. Think The Bells of St. Mary’s,with nuns and priests and Irish brogue and choirs singing Latin hymns. Then throw in the Bowery Boys, the soft-hearted tough guys wisecracking on the corner.

The difference, of course, is that MacDonald’s ambivalence runs deep, he also sees the drug addicts and dealers, and the grinding poverty. Doyle Driedger didn’t. But, MacDonald is standing in Southie as an adult when he sees this scene, Doyle Dreidger is writing from memory.

Nostalgia is a funny thing, and it’s not something to be dismissed, as many academics and laypeople do. It is, in my books, an intellectually lazy and dishonest thing to do. Nostalgia is very real and is something that tinges all of our views of our personal histories.

But what I find more interesting here are the congruencies between what MacDonald and Doyle Driedger writes, between what MacDonald says in All Souls and what he said in his talk last month in Rhode Island, and what the old-timers from Griff and the Pointe told me whenever I talked to them. There was always this nostalgia, there was always this black humour in looking back. I also just read Roddy Doyle’s Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, about a kid growing up in Dublin’s Barrytown, a fictional inner-city neighbourhood. Through Paddy Clarke, Doyle constructs an idyllic world for a boy to grow up in, as he and his mates owned the neighbourhood, running around in packs, just like the kids in Southie MacDonald describes, and just as MacDonald and his friends did when they were kids.

I don’t know if this is something particular to Irish inner-city slums or not. But I do see this tendency as occurring any time I talk to someone who grew up in such a neighbourhood, or read stories, whether fiction or non-fiction, to say nothing of the music of the Dropkick Murphys (I’m thinking, in particular, of almost the entirety of their first album, Do Or Die, or the track “Famous for Nothing,” on their 2007 album, The Meanest of Times), I’m not one for stereotyping the Irish, or any other group for that matter, I don’t think there’s anything “inherent” to the Irish, whether comedy, fighting, or alcoholism. But there is something about this view of Irish slums.

Bono Vox, Corporate Stooge

June 26, 2013 § 2 Comments

In today’s Guardian, Terry Eagleton gets his hatchet out on Ireland’s most famous son, Paul Hewson, better known as Bono, the ubiquitous frontman of Irish megastars/corporate behemoth, U2. Eagleton is ostensibly reviewing a book, Harry Browne’s, Frontman: Bono (In the Name of Power), which sounds like a good read. Eagleton’s review, though, is a surprisingly daft read by a very intelligent man, one of my intellectual heroes.

He takes Bono to task for being a stooge of the neo-cons. For Bono sucking up to every neo-con politician from Paul Wolfowitz to Tony Blair and every dirty, smelly corporate board in the world in the line of his charity work. Eagleton even takes a particularly stupid quote from Ali Hewson, Bono’s wife, about her fashion line, to make his case. Now, just to be clear, I think Bono is a wanker. I love U2, they were once my favourite band, and The Joshua Tree is in my top 3 albums of all-time. But Bono is a tosser. He can’t help it, though, he’s like Jessica Rabbit, he was just made that way. Eagleton, for his part, essentialises the Irish in a rather stupid manner as an internationalist, messianic people, and says, basically, Bono and his predecessor as Irish celebrity charity worker, Bob Geldof, were destined to be such. Whatever.

I’m more interested in Eagleton’s critique of Bono as a corporate/neo-con stooge. It’s a valid argument. Bono has coozied up to some dangerous and scary men and women in his crusades to raise consciousness and money for African poverty and health crises. But, I see something else at work. A couple of years ago, there was news of a charity organisation seeking to use Coca-Cola’s distribution network in the developing world to get medicine out there. I thought it a brilliant idea, but, perhaps predictably, there was blowback. Critics complained that this would then give Coca-Cola Ltd. positive publicity and that it did nothing to stunt Coca-Cola’s distribution, blah blah blah. Sure, that’s all true, but perhaps it would be a good thing if needed medicines were distributed through Coke’s network, especially since Coca-Cola Ltd. was more than willing to help out? Maybe the end result justified the means?

And so, reading Eagleton on Bono today, I thought of Cola Life (the charity working with Coke). And I thought, it’s certainly true that Bono has worked with some skeezy folk. But, if the end result is worth it, what’s the problem? If working with the likes of Tony Blair (hey, remember when everyone loved Tony Blair?!?) and Paul Wolfowitz and Jeffery Sachs actually can lead to positive developments for Africa and other parts of the developing world, is it not worth giving it a try? Or is it better to sit on our moral high grounds in the developed world and frown and shake our heads at the likes of Cola Life and Bono for actually trying to work at the system from within for positive change?

I’ve always been struck by a Leonard Cohen lyric, the first line of “First We Take Manhattan”: “They sentenced me to twenty years of boredom/For trying to change the system from within.” Cohen there summed it up, working within the system for change and revolution is boring, it’s not glamorous, it’s not glorious. But my experience has taught me that it works, and more positive change can be affected through pushing from within the system than from without it. It doesn’t mean it’s always all that ethically clean, either, sometimes you have to get dirty to do a wider good, and I think that’s what Cola Life and Bono are doing on a much bigger, grander, and more impressive scale. And I think the Terry Eagleton’s of the world are living in the past, with their moralistic tut-tutting, all the whilst sitting on their hands and doing little to actually do something to bring about positive change.

Ten Thousand Saints and the Nostalgia of the Record Store

March 12, 2013 § 2 Comments

Last week I read Eleanor Henderson‘s excellent début novel, Ten Thousand Saints. This was a book I randomly came across, and, like most books I randomly come across, I was lucky. Ten Thousand Saints tells the story of Jude, a disaffected teenager in Burlington, Vermont (disguised as Lintonburg, for reasons I don’t quite understand since the rest of Vermont gets to keep its names), a sad sack little city about two hours from Montréal on Lake Champlain. Jude, I should also point out, is about a year older than I am. His best friend, Teddy, dies of an overdose on New Year’s Eve 1987, after he and Jude huff pretty much everything, including freon from an air conditioner, but Teddy also did coke for the first time, introduced to him by Eliza, Jude’s step-sister, who’s in town for a few hours from NYC. Teddy’s older brother, Johnny, also lives in NYC.

The novel then follows Jude, Johnny, and Eliza through the hardcore scene in the NYC underground in the late 80s (looking at Henderson’s picture on her website, she does not look the sort who would). Jude transforms from a pothead huffing high school dropout in Burlington to a straight-edge hardcore punk in NYC, frontman of his own band, the Green Mountain Boys (a clever play on their Vermont roots and Ethan Allen during the War of Independence). Henderson does a great job of illuminating the culture of the hardcore scene of the late 80s, both in NYC and around the rest of the East Coast, as well as issues of gentrification on the Lower Eastside of Manhattan, especially around Tompkins Park in Alphabet City, where Johnny lives, and around St. Mark’s Place, where Jude sometimes lives with his father.

Ten Thousand Saints made me nostalgic. At the other end of the continent, in Vancouver, I was starting to get into some of this music, if not yet the scene. Many of the bands Henderson references were in my cassette collection by 1989-90, a couple of years after Jude and Johnny were rocking out in the Green Mountain Boys. Though I cannot, for the life of me, figure out why the standard bearers of the straight edge scene in the late 80s, Fugazi, are not mentioned, though Ian McKaye’s earlier band, Minor Threat, are the gods of Jude, Johnny, and their crowd. What made me nostalgic was record stores. This is how Jude got into the scene in NYC in the first place, hanging around the record stores of the Lower East Side.

As I mentioned in my last piece here, on the Minutemen, Track Records in Vancouver was where I began to discover all these punk and hardcore bands in my late teens. Track stood on Seymour Street, between Pender and Dunsmuir, and as you went up the block, there was an A&A Records and Tapes, then Track, then A&B Sound, and then Sam the Record Man. Two indies and two corporate stores. And between the four of them, you could find anything you wanted and at a reasonable price. Zulu Records also stood on West 4th Avenue in Kitsilano, a short bus ride from downtown on the Number 4 bus. Of those stores, only Zulu remains. I’m in Vancouver right now, and I think I’m going to make my way over there today.

But it was in record stores that kids like me learned about this entire universe of punk and alternative music in the late 80s. In places like Track and Zulu, we heard the likes of Fugazi and the Minutemen, as well as the Wonderstuff and Pop Will Eat Itself and the Stone Roses playing on the hi-fi. This is where we could find the alternative press and zines, I found out about all these British bands from the NME and Melody Maker. You’d talk to the guys working in the stores (and it was almost always guys, rarely were there women working in these stores), you’d talk to the older guys browsing the record collections about what was good. Some of these guys were assholes and too cool to impart their wisdom, but most of them weren’t. And then you’d rush home to the suburbs and listen to the new music, reading the liner notes and the lyrics as you did.

For the longest time, I held out against digital music. I liked the physical artefact of music. I liked the sleeve, the liner notes and the record/cassette/cd. In part, I liked it because of the act of buying it, of going into the record store, even the corporate ones, listening to what was playing in the store, looking around and finding something. There’s not many record stores left. The big Canadian chains are all dead and gone. Same with the big American ones. In Boston, the great indie chain, Newbury Comics, isn’t really a record store anymore. The flagship store on Newbury St. has more clothes, books, movies, and just general knick knacks than music. Montréal had a bunch of underground stores up rues Saint-Denis and Mont-Royal, but they’re slowly dying, too. And here in Vancouver, the only one I know of is Zulu (though I’m sure there’s more on the east side, on Main, Broadway or Commercial).

I miss the community of music, it just doesn’t exist anymore. I suppose if I wanted to, I could find it online, discussion groups and the like. But it’s not the same. There’s no physical artefact to compare and share. There’s just iTunes or Amazon.

“We Jam Econo” D Boon and the Minutemen

February 8, 2013 § 1 Comment

While laid up sick this week, I finally got to see “We Jam Econo: The Story of the Minutemen,” about the iconic punk band, the Minutemen. The Minutemen came to an untimely end on 22 December 1985 when frontman and guitarist, D Boon, was killed in a car accident just outside Tucson, Arizona, as he and his girlfriend made their way to visit her family for Christmas. The other two members of the Minutemen, bassist Mike Watt and drummer George Hurley, were devastated, of course. To this day, everything Watt produces is dedicated to D boon’s memory.

I first got into the Minutemen a few years later, around 1990 or so when I got my hands on fIREHOSE’s 1989 album, fROMOHIO. This was the band that Watt and Hurley formed in the aftermath of D. Boon’s death with Ed Crawford. I was drawn to the mixture of Crawford’s jazzy guitar, combined with Watt’s amazing bass sounds. But, what attracted me the most was Hurley’s drumming. I honestly don’t think there’s another drummer I’ve ever heard that touched Hurley, except for maybe Jimmy Chamberlin in the Smashing Pumpkins. But as I obsessed about fIREHOSE, I was directed towards the Minutemen by one of the guys who worked at the old Track Records on Seymour Street in downtown Vancouver.

I first got into the Minutemen a few years later, around 1990 or so when I got my hands on fIREHOSE’s 1989 album, fROMOHIO. This was the band that Watt and Hurley formed in the aftermath of D. Boon’s death with Ed Crawford. I was drawn to the mixture of Crawford’s jazzy guitar, combined with Watt’s amazing bass sounds. But, what attracted me the most was Hurley’s drumming. I honestly don’t think there’s another drummer I’ve ever heard that touched Hurley, except for maybe Jimmy Chamberlin in the Smashing Pumpkins. But as I obsessed about fIREHOSE, I was directed towards the Minutemen by one of the guys who worked at the old Track Records on Seymour Street in downtown Vancouver.

The Minutemen blew my mind. D. Boon’s was already legendary. Vancouver had been central to the development of North American punk in the late 70s, and the city’s biggest band, DOA, had shared several bills with the Minutemen down in California. Track Records even had a Minutemen poster on the wall. I quickly became obsessed with the Minutemen’s 1984 double album, Double Nickels on the Dime. I loved Watt’s explanation of how this title came about; it was a response to Sammy Hagar’s complaint that he couldn’t drive 55. Apparently ‘double nickels” means 55mph, the speed limit in those days.

Every time I listen to the Minutemen these days, I just get incredibly sad. D Boon has been dead for longer than he was alive by this point, he was 27 when he died 28 years ago. Watt has aged, he still makes incredible music. But, simply put, and as trite as it sounds, D Boon never got a chance to age. His music always had a sneer in it, but what I loved most was always his political bent. He was a good working class boy (as were Hurley and Watt), and the politics of the working classes pervade his music. I was always drawn to this as a working class kid myself. In fact, this is what drew me to punk in the first place, it was a working-class movement. D Boon sang about how the working classes got screwed, his music reflected his own values of hard work, something instilled in him by his mother, who had died young herself, in 1978. More than that, D Boon was articulate, he didn’t look like a dumb punk trying to find big words when he spoke, he sounded like a smart working class dude. I liked that most about him. Too many other working class punks sounded like stupid mooks when they spoke (I’m looking at you, Hank Rollins).

But the Minutemen weren’t just anger. Their music was smart, a mixture of punk, funk and jazz, anchored by the incredible skill of Hurley. This jazz and funk influence (especially through Watt’s bass) added a level of fun and bounce to the music that other punks lacked. And Watt and D Boon were also just as influenced by The Who and Credence as anything else. These influences made them probably the most musically and technically proficient punk band of the era. They also mellowed as they got older, as both D Boon and Watt grew into their talent. This is what makes Double Nickel so sad for me (to say nothing of Three Way Tie (For Last), their last album, which came out a week or two before D Boon died). The Minutemen were evolving away from punk, they still sounded so unlike anything else out there. They weren’t becoming a basic rock band, they were far too smart for that.

Watt carries this spirit on in everything he does. His bass guitar was instrumental to the Minutemen’s sound. This is precisely what makes it all so sad, I always imagine what Watt would sound like if he and D Boon and George Hurley were still making music together. The Rolling Stone review of Three Way Tie (For Last) prophecies that “You can bet that in ten years there’ll be groups who sound like the Minutemen — maybe they’ll even cover their songs.” In 1996, no one sounded like the Minutemen. In 2006, no one sounded like the Minutemen. And in 2016, no one will sound like the Minutemen. They were a unique, one of a kind band.

This last clip comes from an interview the Minutemen did in the early fall 1985, just a few months before D Boon checked out.

Le Reigne Elizabeth

October 19, 2012 § Leave a comment

The Queen Elizabeth Hotel on blvd. René-Lévesque has fascinated me ever since I was a kid. Structurally and aesthetically, it is one of the ugliest buildings in the downtown core of Montréal. Built in a neo-brutalist style usually reserved for university campuses, the Queen Elizabeth is nonetheless the swishest hotel in Montréal. It is also the largest hotel in Montréal and Québec, with over 1,000 rooms. The other thing that has fascinated me since the mid-70s is the name of the hotel. How does a hotel in the middle of Montréal, the metropole of Québec, end up being named after the Queen? Better yet, what’s with the incongruity of the name in French, Le Reigne Elizabeth, with the masculine article there before the feminine monarch?

When the hotel was first proposed back in 1952, there was an upsurge of love for the monarch in English Canada. Queen Elizabeth II had just ascended the throne, and around the former British Empire, people were gaga over the queen, somewhat like people are currently in a tizzy over the former Kate Middleton. However, the 1950s also saw the rumblings that led to the eruption of the Quiet Revolution in Québec in 1960. There was an upsurge of québécois nationalism in the city and province as well. Indeed, nationalists argued that the Canadian National Railways should name the new hotel after the founder of Montréal, Paul de Chomedy, sieur de Maisonneuve. Nonsense, responded the CNR’s president, Donald Gordon: Canada is a Commonwealth nation, and the head of the Commonwealth is Queen Elizabeth II. Since he was the one building the hotel, he won the debate.

As for the masculine article in the hotel’s French name, well, it turns out that refers to the implied ‘hotel’ in the name, and hotel is masculine. There you have it.

The Queen Elizabeth Hotel, of course, has lived up to its reputation. The Queen herself has rested her head on its pillows four times, and her son, Prince Charles, has also visited. The NHL entry draft was held there pretty much every year until 1979. But, of course, the most famous event to have occurred in the Queen Elizabeth is the “bed-in” of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, 26 May-2 June 1969. Lennon and Ono had been denied entry to the United States, because Lennon had a cannabis conviction from 1968. A bed-in was planned for New York City. So now the plan had to be changed, and so Lennon and Ono bedded down in the Queen Elizabeth for their second Bed In for Peace (the first had been in Amsterdam 25-31 March). During the Montreal bed-in, the anthem “Give Peace a Chance” was recorded by André Perry.

The Queen Elizabeth Hotel, of course, has lived up to its reputation. The Queen herself has rested her head on its pillows four times, and her son, Prince Charles, has also visited. The NHL entry draft was held there pretty much every year until 1979. But, of course, the most famous event to have occurred in the Queen Elizabeth is the “bed-in” of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, 26 May-2 June 1969. Lennon and Ono had been denied entry to the United States, because Lennon had a cannabis conviction from 1968. A bed-in was planned for New York City. So now the plan had to be changed, and so Lennon and Ono bedded down in the Queen Elizabeth for their second Bed In for Peace (the first had been in Amsterdam 25-31 March). During the Montreal bed-in, the anthem “Give Peace a Chance” was recorded by André Perry.

Les Expos, Nos Amours: Gone, but not Forgotten

April 25, 2011 § Leave a comment

Last October, as the Expos should have been winning the World Series, I wrote a piece at the National Council on Public History‘s blog, Off the Wall, about the strange marketing after life of Nos Amours. This provoked a steady stream of comments, both on that site and into my inbox, as well, to a lesser degree, here at Spatialities. One of my readers, Sarah, pointed out Montréal rapper Magnum .357′s track “Expos Fitted.

It seems that rap has emerged as a key component to remembering our long gone baseball team here in Montréal. Aside from Mag .357, Anakkin Slayd, who is more famous right now for his viral hit, “MTL Stand UP”, also wrote a song about the Expos, “Remember”.

The Real and True Story of the Birth of Rap Music

April 2, 2011 § Leave a comment

First, I have been MIA for a bit from here @ Spatialities and from my duties over @ Current Intelligence. I have been off on medical leave from work since February. Regular programming here and @ CI will resume shortly. In the meantime, I am spending a lot of my time recovering reading. I have been ploughing through books, taking advantage of all of this free time to read. I’ve been reading all kinds of things, both fiction and non-fiction, everything from paperback novels to philosophical ones, from philosophy to history and current affairs. The fruits of my labours will soon be appearing on my CI blog, “Advance Copy.”

Anyway.

I teach Western Civ every semester. Teaching the same course over and over again, well, I need to find ways to make it interesting. And for the students, too, they are forced to take the course, it’s a requirement in the Social Sciences programme at John Abbott College. So, we all need coping mechanisms. One is obviously humour. When we get to the Reformation, we get to that great anti-Semite, Martin Luther (who my students inevitably confuse with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King). And whilst explaining how the Lutheran Reformation came to be, I discuss the protection Luther received from Frederick of Saxony, who gave Luther shelter against the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. As an aside, Frederick was actually the pope’s choice to become the next Holy Roman Emperor in 1519. Turns out it was a good thing he didn’t become Holy Roman Emperor, since Frederick was instrumental in the Lutheran Reformation.

Back to the main point: there is this great picture of Luther and a bunch of other men standing behind Frederick, a rather large, portly man, who is standing in what can only be described as his b-boy stance, wearing some heavy gold jewellery around his neck (see picture below), with his posse (Luther is the sour-faced dude at Frederick’s right shoulder). I explain to my students that Frederick was actually the first gangsta rapper in history.

It turns out, however, I was wrong. Frederick was not the first gangsta rapper in history. Moreover, rap was not, as has long been thought, invented in the Boogie Down Bronx in the 1970s. Nope, rather, rap was invented in the early 7th century Before Common Era by the Assyrian emperor, Sennacherib, following his defeat of the Elamites in 691 BCE.

Sennacherib had his court historian record the events of the war, from the emperor’s point of view. The account of the war is pure braggadocio, hype, and chest-thumping, not unlike early hip hop. See, for example, KRS-One’s video for “Outta Here” from 1993.

Compare KRS-One’s lyrics with Sennacherib’s account, taken from a quote in John Keegan’s A History of Warfare, the quote itself taken from H. Saggs’ The Might That Was Assyria:

I cut their throats like sheep…My prancing steeds, trained to harness, plunged into their welling blood as into a river; the wheels of my battle chariots were bespattered with blood and filth. I filled the plain with the corpses of their warriors like herbage…[There were] chariots with their horses, whose riders had been slain as they came into the fierce battle, so that they were loose by themselves, those horses kept going back and forth all over [the battlefield]…As to the sheikhs of the Chaldaceans [Elamite allies], panic from my onslaught overwhelmed them like a demon. They abandoned their tents and fled for their lives, crushing the corpses of their troops as they went…[In their terror] they passed scalding urine and voided their excrement in their chariots.

Seriously, just throw a beat under that, and you’ve got a dope track. So, hip hop, it turns out, is approximately 2800 years older than we thought it was.

Magnum .357: “Expos Fitted”

October 23, 2010 § 1 Comment

A tip of the hat to Sarah, who posted a comment in response to Nos Amours (and check out the original post at NCPH’s Off The Wall), directing us to a video of Montréal rapper Magnum .357 and his début single/video, “Expos Fitted.” She posted the video in her comment, but I think it deserves wider exposure. I especially love the nostalgia of the Expos dressed up as gangsta rap.

Mag .357 is practically my neighbour, he hails from Montréal’s Anglo-Black neighbourhood, Little Burgundy, which is across the Lachine Canal from me here in Pointe-Saint-Charles. Burgundy is a curious neighbourhood, as it is home to both inner-city gang violence and yuppies who have gentrified the old worker’s cottages and triplexes that line the streets. It is also one of the oldest Black communities in Canada.

Burgundy also has a long history of being a centre of entertainment in Montréal. In the wake of Prohibition in the US and before the rise of Jean Drapeau as mayor of the city in 1960, Burgundy was home to various jazz clubs, most notably the legendary Rufus Rockhead’s Paradise. Oscar Peterson and his student Oliver Jones, the two greatest jazz musicians this country has ever produced, also grew up on the streets of Burgundy. In this sense, Mag .357 is carrying on the tradition.

I have to say, I love this track and I’ve been checking out his MySpace page. Enjoy.

The Apocalypse is Nigh

May 16, 2010 § Leave a comment

We interrupt regularly scheduled programming here on Spatialities to bring you the following developing news: this weekend, the Théâtre Corona, here in Montréal, held a 2-night tribute to Phil Collins: Dance into the Light: Le Meilleur de Phil Collins. The Phil Collins impersonator is Martin Levac, billed as “the best impersonator of Phil Collins” in the world, and his show spent last spring at Le Capitol in Québec before embarking on a 20-city European tour.

Yes. Phil Collins merits a tribute show. I always thought that in order to merit a tribute, an artist had to be, well, an artist. A Phil Collins tribute. WTF?!?

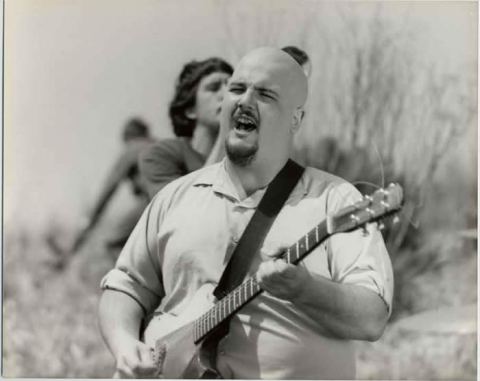

Punk Rawk, Maaaaan!

January 14, 2010 § Leave a comment

I managed to not sound entirely daft in an interview with the Halifax Commoner on the place of women in punk rock. That’s a goal in and of itself, no?