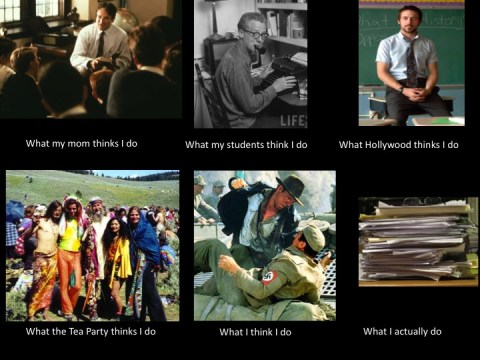

What Historians Do

February 19, 2012 § 2 Comments

Apparently there is a meme on Twitter about historians. I don’t actually pay much attention to these kinds of things, mostly because they multiply my procrastination ratio to places that I am uncomfortable being. Nonetheless, this tweet came through my timeline this morning, it originally comes from Waitman Boern, who is at Loyola, Chicago.

Bloody hilarious. I spent my Saturday yesterday doing just that, marking a stack of papers.

Remembering Zmievskaya Balka, Rostov-On-Don, Russia, 1942

February 15, 2012 § 2 Comments

My sister-in-law’s husband is spear-heading this campaign. Please circulate this widely. The actions of the Rostov-On-Don city council are disgusting and an attempt to erase history and are thinly veiled anti-Semitism. Let us ensure they cannot get away with this:

Please disseminate the following press release by the committee organizing the 70th Anniversary Commemoration of Zmievskaya Balka – “Russia’s Babi Yar.” Scheduled events will commemorate a series of mass executions by Nazis just outside the city of Rostov, Russia between 1942 and 1943. While grassroots commemorative initiatives have taken place since the early 1990s by Rostov’s small Jewish community, 2012 marks the first major effort to commemorate the Holocaust in Rostov publicly.

The planning process takes place amidst conflict over the recent decision by Rostov government officials to take down a memorial plaque that was erected in 2004, identifying most of the 27,000 Zmievskaya Balka victims as Jewish. The replacement plaque does not mention Jews, but rather the “peaceful citizens of Rostov-on-Don and Soviet prisoners-of-war.” Having struggled for decades to battle exclusionary nationalism and anti-Semitism in the construction of public memory of the events at Zmievskaya Balka, Rostov’s Jewish community and the diaspora it has yielded have been spurred to action and are seeking support as well as information, donations of artifacts and broad participation in the commemorative activities.

70th Anniversary Commemoration of Zmievskaya Balka – “Russia’s Babi Yar”

Rostov on Don, Russia, August 12-14, 2012

Organizing Committee Announcement

August 2012 marks the 70th anniversary of the beginning of mass executions of Jews by the Nazis in Rostov on Don, Russia, in the Zmievskaya “balka” – a huge ravine on the edge of this southern Russian city of over one million residents. Here more than 20,000 people were killed. The greatest number of victims, including poisoned children, died on August 11 and 12, 1942. For Russia, this place holds the symbolic importance of Ukraine’s Babi Yar. There is no place in Russia where a greater number of Holocaust victims lost their lives. Others were also killed here: Soviet citizens of other nationalities, prisoners of war, resisters, psychiatric hospital patients, and others.

In 1975, a memorial was erected at the Rostov “Zmievskaya Balka” and a small museum was built there.

This anniversary of the Rostov tragedy, dedicated to the memory of the victims, deserves attention on an international level, as this place has relevance for many famous people connected with the history of the Holocaust. Among those executed here was world-renowned psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein (about whom several feature films have been made). Both before and after the war Alexander Pechersky lived in Rostov. Pechersky was the organizer of the only successful mass escape from a Nazi death camp — the escape from Sobibor. A British film about his exploits was well received.

Two other prominent Jewish leaders are connected to Rostov: Fedor Mikhalchenko, rescued in Buchenwald as a child and later to become Chief Rabbi of Israel, and Meir Lau, present day chairman of the Board of the museum “Yad Vashem.” Meir Lau, who is planning to attend the rememberance events, will be one of the honored guests. Government delegations, including the U.S. and Israel, are being invited.

Please note that August 11, 2012 falls on a Saturday (the Sabbath), which means that no memorial services will be held on this day.

August 12-14, 2012

Planned memorial /educational activities in Rostov-on-Don include the following:

– A memorial evening in one of the city’s largest halls on August 12th ;

– A ceremony at the Zmievskaya Balka on the morning of 13th August;

– Opening of a new exhibit at the Museum of the “Zmievskaya Balka” (August 13);

– International conference in memory of Sabina Spielrein on the “Fate of Scientists during the Holocaust” (August 12th -13th );

– A seminar for teachers of Russia, CIS and the Rostov Region, “Lessons of the Holocaust – the path to tolerance” (12th -14th August);

– A Holocaust Film Festival to feature both documentary and feature films;

We are seeking support from colleagues and interested parties across the globe.

How You Can Help:

– Join the organizing committee.

– Donate money to help us hire organizers and researchers.

– If you have any information about the victims of Zmievskaya Balka or their relatives or descendants, please contact us.

– Do you read Russian? When searching for the names of the dead, we found the miraculously-preserved records of the Rostov synagogue circa 1850-1921. Please help us translate these records, as well as other research articles on the events at Rostov, from Russian into English so that they may be more widely disseminated.

– Contribute to memorial books or consider donating to the exhibit.

– Spread the word: disseminate this press release widely.

Please contact us for more information.

Ilya Altman: +79169064998, altman@holofond.ru

Yuri Dombrovskiy: +79037553043, yuri.domb@gmail.com

Web links:

Constructing Landscapes

February 8, 2012 § 1 Comment

[note: I originally wrote this article nearly 4 years ago for a site that no longer exists; as the ideas contained in this piece are still of interest to me, I am re-publishing it now, mostly for my own purposes going forward. I have updated parts of this article that were dated.]

I read a fascinating post at Geoff Manaugh’s BLDG Blog about a new video game from LucasArts that allows the player to modify the game’s battlespace through various (fictive?) technologies. And while that in an of itself is interesting, what struck me most was Manaugh’s reference to historian David Blackbourn’s book, The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany.

Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, 1740-86

Blackbourn argues that modern Prussia (a pre-cursor state to today’s Germany) was literally “made,” or at least its coastline was, during the reign of the Frederick the Great, who ruled Prussia from 1740-86. During this period, dykes were built, bogs and marshes were drained, land along the shoreline was created, moulded, and so on. Vegetation was imported and shifted from one locale to another along Prussia’s coastline. Frederick’s imperial projects in Prussia were not, in fact, unlike the works the Dutch did along their coastline to make the Netherlands both more productive and more liveable.

Blackbourn’s argument is an interesting one, to be sure: that modern Prussia (and therefore, today’s Germany) was literally made in the shape that Frederick desired; the land was sculpted. This was done not to give him more land to rule over, as Manaugh suggests, but to increase Prussia’s wealth. In the pre-Adam Smith era, the wealth of nations was measured in agricultural production. Indeed, this was a pretty common Enlightenment argument, popularised by François Quesnay and his colleagues in France, the Physiocrats.

Frederick was keenly interested in Enlightenment theories, and corresponded with many leading thinkers of the era. He even hosted the idiosyncratic French thinker Voltaire at his palace at Sans Souci for a while, until their particular personalities led to conflict. Adam Smith, for his part, was a colleague and correspondent of Quesnay and the Physiocrats, and developed his own theories on the wealth of nations, in part from this correspondence.

What’s of interest here is Blackbourn’s argument. Germany isn’t the only nation to be literally made from the ground up. All modern, industrialised, militarised Western nations are so-made. Many former colonial territories, such as India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, also fall into this category. Our landscape is, all around us, “made”, both in the physical and intellectual sense. Our landscape is only as it is because we – as a culture, a society, as individuals – see it in a certain way.

More than this, the landscapes of these industrialised, Western nations (and their former colonies) are man-made in many ways. Germany and the Netherlands are but two examples. England, also, is crisscrossed by canals, constructed by re-shaping the landscape of the nation to transport goods and commodities during its Industrial Revolution. Indeed, England is a good example of the forging, or of a landscape, as it has been largely deforested in order to create the fuel for industrialisation, and the landscape for industrialisation.

More than this, the landscapes of these industrialised, Western nations (and their former colonies) are man-made in many ways. Germany and the Netherlands are but two examples. England, also, is crisscrossed by canals, constructed by re-shaping the landscape of the nation to transport goods and commodities during its Industrial Revolution. Indeed, England is a good example of the forging, or of a landscape, as it has been largely deforested in order to create the fuel for industrialisation, and the landscape for industrialisation.

There’s more. All countries are made, or manufactured, in the sense Blackbourn means. In some cases, this is a natural phenomenon, such as the erosion of sea shores and river banks and coastlinesIn others, it’s man-made. Take, for example, the Gulf Coast of the United States and, in particular, New Orleans. We saw how much of that coast was devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. While the hurricane was devastating enough, what failed in the case of New Orleans were man-made defences around the city, located as it is on the delta of the Mississippi River, and on the shores of Lac Pontchartrain.

New Orleans after Katrina

Close to 49% of the New Orleans’s geographic footprint is below sea level, and large parts of the city are sinking. New Orleans averages out at 0.5 metres below sea level, with some parts reaching 5 metres below sea level; but the city has been made a viable location for settlement, industrialisation, and economic activity due to mitigating works being built on the Mississippi and Lac Pontchartrain. All of this economic and industrial activity in New Orleans and along the Gulf Coast has also meant the destruction of nearly 5,000 square kilometres of coastline in Louisiana alone in the twentieth century, including many off-shore islands, all of which used to protect New Orleans and the Mississippi delta.

Thus, when Katrina hit 6 ½ years ago, on 28 August 2005, there were few natural defences left to protect New Orleans. The man-made “improvements” to New Orleans and the surrounding area were simply insufficient to deal with a hurricane the force of Katrina, which was classified as a Class 1 or 2 storm. The result was nearly 80 per cent of the city was flooded out, as well as massive social and economic dislocation. Today, New Orleans’s population is still only 60 per cent what it was prior to Katrina.

Getting back to Blackbourn’s argument: his arguments vis-à-vis the creation of modern Prussia can be transported across and around the industrialised Western world. Montréal (the population of Montréal’s metropolitan area is nearly four times the size of that of New Orleans), is the beneficiary of similar modern landscape engineering. The city is located on an island in the middle of the Saint-Lawrence River, and in a cold, northern climate. In the nineteenth century, each spring, during the spring run-off and thawing of the river, the low-lying portions of the city, located near the river bank on the flood plain, were swamped with water.

1886 Flood, Chaboillez Square, Griffintown, Montréal

In 1886, flood waters were over 3 metres deep. The flood led to mitigating works being constructed along the river, the bank was re-landscaped and engineered, dyking was constructed, and so on, all in order to prevent further flooding. This allowed Montréal’s industrial development to continue throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century . This allowed it go through an unprecedented growth cycle that only ended with the Depression of the 1930s, and enabled Montréal to solidify its position as Canada’s metropole (a role it has since lost to Toronto).

This re-shaping of the environment, however, is not limited to the West. More recently, the insta-city of Dubai in the United Arab Emirates has followed suit. Dubai itself is a manufactured landscape, as all cities are to a degree, but in the case of Dubai, the landscape has been purposely re-appropriated for the construction of the city. A more specific example can be seen in the city’s golf courses, for example, the Tiger Woods Dubai golf resort and residences. Golf courses are, in fact, a perfect example of the re-engineering of the landscape, as grass and various other features such as sand traps and water hazards – to say nothing of surrounding vegetation – are imported and planted into foreign

The construction and maintenance (such as irrigation and pesticides) of Dubai’s golf courses, situated as they are in the desert, present us with a massive redevelopment of the landscape, the environmental consequences of which appear to be lost on Woods and his partners in the project. Dubai City itself is an example of environmental re-landscaping for human needs and settlement. Without the sorts of technologies created by the Dutch and the Prussians (to say nothing of the English, Americans, and Canadians), Dubai itself would not exist in its present, insta-city form.

Under London

February 7, 2012 § 5 Comments

I originally wrote this review for Current Intelligence, before I left the publication in the autumn of 2011, so it never saw the light of day there. I am publishing it here as a means of starting a discussion, or thread, concerning the underside of cities. And by that, I don’t mean the criminal underside or something like that, I mean the literal underground of the city. Peter Ackroyd here has written an history of the London underground (and no, not the Tube), an idea I wish other historians and writers would seize upon for other cities. There is an entire world located under our cities, not quite lost Atlantises, but at the very least, the ruins of previous civilisations. But wait! There’s more! The urban infrastructure is also below ground: the telecommunications and electrical wiring, sewers, subways, roadway tunnels and more. The underside is a topic of fascination and revulsion and something I am interested in as an urban historian. In short, I’ll be returning to this theme in coming weeks.

Peter Ackroyd. London Under. London: Chatto & Windus, 2011. 202pp. ISBN: 9780701169916 £12.99

Peter Ackroyd is one of the most prolific authors writing in the English language today, having churned out exactly fifty works of fiction, poetry, and non-fiction in the past forty years, to say nothing of another half-dozen TV shows. While his subjects have been diverse, a constant throughout his oeuvre has been London. Many of his novels have been set there and a decade years ago, he published London: The Biography, followed in 2003 by The Illustrated London and in 2007 by the biography of the great river that flows through the city, The Thames. His latest book, London Under is a product of these three books, as well as his 2009 book, Venice: Pure City. However, London Under reads as leftovers from London and Thames. It’s the story of what’s under London, from natural springs, to the ancient Roman settlement, raunchy sewers, and, of course, the Tube. Certainly a fascinating little book, whether or not London Under is successful is another matter.

What lies beneath the surface is a topic that has transfixed humans since we first evolved away from apes. For the Greeks, the dead went to the great Hades Hall under the world. Grave yards and the undead were a staple of Victorian ghost stories. What lies beneath the sea is still a topic that makes my skin crawl. But there is also an entire underworld that lies beneath our cities. In Roman times, the city’s catacombs provided shelter for the Christians. The Catacombs of Paris have held an eery hold over pop culture since the days of Edgar Allen Poe. Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk has his characters running through the old Byzantine city underneath Istanbul in his novel, The Black Book. And London’s myriad underground tunnels were said to be the home of thieves, street urchins, mobsters, and slavers.

More than just the terror, though, there is a duality to the underground, which Ackroyd acknowledges; it can be both a site of safety and a site of evil and terror. On the bright side, he cites the protection afforded the Christians under ancient Rome. On the dark side, he points to the medieval prison, which was oftentimes a pit in the ground, or the depths of the Tower of London. Indeed, under London are some nasty little places, such as the House of Detention, which was a dank, terrifying prison. But it was during the nineteenth century that the underground began to take on its truly nefarious tone in London, as it was seen as the den of criminals and smugglers who only came out at night. Then there’s what creeps and crawls through the underground: rats, eels, snakes, and other such creepy creatures. Rats, in particular, spark fear in humans, no doubt due to their role in causing the Great Plague in the fourteenth century (to be fair, it wasn’t the rats, it was their fleas, but who’s counting?).

After a general introduction, we are transported back to the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1666 and the discovery of what lay beneath the ruins of the torched city. Ackroyd introduces us to Sir Christopher Wren, the great architect, and his excavations of St. Paul’s Cathedral after the fire. He was surprised to discover, amongst other things, Anglo-Saxon graves, on top of Saxons, on top of Britons, on top of Romans. Along with the Roman remains, he found pavement from Londonium (as it was called during the Roman era) and below that, sand and seashells. London had once lay under the ocean. As for the bodies, Ludgate Hill, the site of St. Paul’s, had long been a sacred burial ground, and was the site of a temple to Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt. After a catalogue of all the neat and not-quite-so-neat things that have bubbled up to the surface of London over the past five or so centuries, we move onto more conceptual and sequential chapters.

From Chapter 3 “Holy Water,” onwards, it’s a whirlwind tour of what lies beneath London. Water, not surprisingly, is the focus of much of the book, a total of five chapters are devoted to water in some form or another, including sewers, pipes, and the buried River Fleet, “the most powerful of all London’s buried rivers.” [p. 52]. Powerful, maybe, but the Fleet was more of an open sewer when it still flowed above ground. Thus, after the Great Fire, Wren sought to re-create the Fleet as a majestic, Venetian-type river that flowed through the City down to the Thames. To this end, he constructed a canal. But this did not turn out so well; by the 1720s, Alexander Pope was using the Fleet as the backdrop to the corruption of Britain in The Dunciad. As commercial activity closed in on the Fleet, it became silted up, and was eventually built over and that’s how we get Fleet street today.

The chapters leading up to that on pipes (Ch. 8), however, read like they were picked up off the cutting room floor from when Ackroyd was writing London and Thames. Perhaps it’s a testament to Ackroyd’s skill as a writer, but these chapters feel effortless, and not in a good way, as if he just rather sneezed them out. They contain a lot of interesting information, but not much more in terms of analysis and organisation.

It is only when we get to the eighth of thirteen chapters that London Under hits its stride. “The Mole Men” tells the story of the men who built the tunnels that lie under the city. The Thames Tunnel is the star of the chapter. Its construction is a fascinating study in engineering, ingenuity, and the sheer terror induced by water. Having grown up in cities that have made great hullaballoo about tunnels under great rivers for transportation purposes, perhaps the story of the Thames Tunnel resonates with me more than most. While the harrowing stories of the gasses under the ground that burst into flame are enough, it is the horror conveyed in the voices of the long-dead workmen on the tunnel when the river broke through: “The Thames is in! The Thames is in!” When it was finally complete in the 1840s, the Thames Tunnel was a financial disaster, costing nearly £500,000 to construct. It was eventually absorbed into the nascent railway system before becoming part of the Underground and, today, the London Overground.

The next several chapters are dominated by the Tube. In particular, I was taken by the chapter on the disused Underground stations that dot the system. The London Underground is enough to boggle the mind at the best of times, servicing some 270 stations (though this is a far site fewer than the 468 served by the New York Subway). In addition to the disused Tube stations, there are “dead tunnels”, empty, abandoned tunnels that run to nowhere off the main lines. (There is a website dedicated to the abandoned Tube stations, entitled, appropriately enough, London’s Abandoned Tube Stations). Being fascinated by underground subway systems and the abandoned and empty tunnels we can see out the windows of the train as we hurtle below the city, I found this chapter to be the most entertaining and rewarding.

On the whole, London Under reads as though it is the B-side to London and Thames double A-Side single. It is breezily written, one can easily sit down to read it in the morning with coffee and finish it by the point it’s time to put dinner on. This has both its virtues and its vices. At its best, London Under is a rollicking tour through subterranean London, well worth the read. At its worst, though, it is as if Ackroyd sneezed it out, with little thought to narrative or analysis, or to even tying it all together, it’s a long recitation of fact. At all times, though, Ackroyd is informative and interesting.

Rural Palimpsests; Or, the Changing Rural Landscape

February 3, 2012 § 9 Comments

About 18 months ago, I wrote this piece about the old Town Commons in Hawley, Massachusetts. I was struck by the history of what could no longer be seen in Hawley at the Town Commons where, in the mid-19th century, there was a vibrant townsite. Hawley also stirred up my own memories of having lived in a ghost town as a teenager, on the old town site of Ioco, British Columbia, now a part of Port Moody, BC. But Ioco, which will eventually become condos, I’m sure, was a (sub)urban townsite. Hawley is a town a few miles west of the Middle of Nowhere.

In urban centres, we see the ruins of past civilisations all around us, whether they are palimpsests of old advertisements on the sides of buildings, or the ruins of buildings, still dotting the landscape. Indeed, I wrote my doctoral dissertation and a book on a neighbourhood that was, at least when I started writing, a ruin: Griffintown, Montréal. A decade ago, the landscape of Griffintown was an urban ruin, the foundations of the old Irish-Catholic Church, St. Ann’s, poking through the grass of Parc St. Ann/Griffintown; the rectory of the French Catholic Church, Ste-Hélène still stands, but the church is long gone, just a few corner stones and the remains of an iron fence are left. But this is a city, and cities, we are constantly reminded by scholars, poets, novelists, film-makers, etc., are living organisms, built to be rebuilt, constantly evolving and changing. By definition, then, the rural landscape is unchanging and constant.

In urban centres, we see the ruins of past civilisations all around us, whether they are palimpsests of old advertisements on the sides of buildings, or the ruins of buildings, still dotting the landscape. Indeed, I wrote my doctoral dissertation and a book on a neighbourhood that was, at least when I started writing, a ruin: Griffintown, Montréal. A decade ago, the landscape of Griffintown was an urban ruin, the foundations of the old Irish-Catholic Church, St. Ann’s, poking through the grass of Parc St. Ann/Griffintown; the rectory of the French Catholic Church, Ste-Hélène still stands, but the church is long gone, just a few corner stones and the remains of an iron fence are left. But this is a city, and cities, we are constantly reminded by scholars, poets, novelists, film-makers, etc., are living organisms, built to be rebuilt, constantly evolving and changing. By definition, then, the rural landscape is unchanging and constant.

Don’t believe me? Spend a bit of time reading literature set in the countryside. Or watch movies. Read poems. The landscape of the country side is eternal and unchanging. Entire nations have been built on the mythology of the countryside (I’m looking at you, Ireland!). Here in Québec, Maria Chapdelaine, a major novel of the early 20th century nationalist school explicitly tied the virtue of the nation to the land. The anti-modernists of a century ago celebrated the unchanging “natural” landscape of the countryside as a tonic for the frayed nerves of modern man. In Canada, the Group of Seven built their entire careers/legends on representing Ontario’s mid-North back to us as the nation. Watch a Molson Canadian ad these days, and you’ll learn that Canada has more square miles of “awesomeness” than any other country on Earth. And all that awesomeness is somewhere in the wheat fields of Saskatchewan. But the rural landscape DOES change and evolve, as the Old Hawley Town Commons will tell you.

This was brought all the closer to me in late November, when I travelled out to Saint-Sylvestre, Québec, which is located about 70km south of Québec City, in the Appalachian foothills. I was there because a long time ago, I wrote my MA thesis on the Corrigan Affair, which erupted in Saint-Sylvestre on 17 October 1855 when Robert Corrigan, an Irish-Protestant bully, was beaten to death by a gang of his Irish-Catholic neighbours. The mid-1850s saw the height of sectarianism in Canada and a murder case involving the two groups of Irish proved to be too much for many Anglo-Protestant Canadians to take and a national crisis broke out. By the time the Affair was over in 1858, not only had Corrigan’s murderers been acquitted of all charges, the McNab-Taché coalition government had fallen. All these years later, I had it in my mind that it was time to do something with the Corrigan Affair. I had done my best to avoid it after I finished my MA, I did attempt to write an academic article, but it seemed to me to be too good a story to be wasted in a journal article that no one would ever read. So I have decided to write a book that no one will ever read, but at least a book is a physical thing, something to offer tribute to this rather amazing story that erupted onto the front pages of newspapers across British North America from a rural backwater. So it was out to Saint-Sylvestre to meet Steve Cameron, a local man who has a deep interest in the Corrigan Affair and the history of the Saint-Sylvestre region in general.

Steve offered to give me the grand tour of the landscape, where the Corrigan Affair took place. I don’t really know what I expected, but I certainly didn’t expect what I saw: the entire landscape of Saint-Sylvestre and the landscape of the Corrigan Affair is gone, completely changed in the 155 years since Corrigan’s death. He was beaten on the county fair grounds; the site where he was beaten is completely non-descript today, just a corner of a farmer’s field. Corrigan’s homestead is covered with scrub and a random cross someone threw up sometime in the past century. Where the farm of Corrigan’s friend, Hugh Russell was once located there is nothing but high tension electrical wires, forest, and a dirt road passing by in front. There is no evidence of human habitation ever having stood there. Where the Protestants had their burial ground here in the backwoods of Saint-Sylvestre/Saint-Gilles, there is nothing left but a stone wall, though the grave yard has been carefully and lovingly restored by Steve’s organisation, Coirneal Cealteach.

In short, the rural landscape is just as dynamic of that of the city. In Saint-Sylvestre, the mostly Irish-Catholic farmers were settled on poor farming land in a harsh and unforgiving landscape; their descendants left. And in their stead, nature reclaimed its place. When I first began studying Griffintown a decade ago, Talking Heads’ song “Nothing But Flowers” kept creeping into my head as I pondered the ruins of the churches, the trees growing in vacant lots and the vegetation in the cracks of the concrete. But “Nothing But Flowers” applies just as much to Hawley or Saint-Sylvestre or countless other rural landscapes once settled by humans who have long since moved on.

The End of History? Or, Maybe Fukuyama was Right After All?

August 22, 2011 § 1 Comment

I have always thought Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man to have been an elaborate joke Fukuyama pulled on all of us. How else to explain that Fukuyama still has a career and is still taken seriously? But, maybe he was right, in a sense anyway. I recently read Doug Saunders’ Arrival City back-to-back with Mike Davis’ Planet of Slums. Both books are instructive and informative, both have fundamental problems. Saunders is way too optimistic and Pollyana-ish, and Davis is far too much of a Debbie Downer.

Saunders thinks cities are just about the greatest things ever and that they’ll lead to the liberation of humanity across the globe, the poor will rise out of their ghettos and slums, they will become middle class, and we’ll all live happily ever after. I exaggerate his argument, of course. But one thing about the book that really annoyed me was this on-going sense that slum-dwellers should have expected to have been consulted about the construction of housing projects in Western Europe and North America. It’s a fine sentiment, but it’s so ahistorical it made me spit out my coffee when I read it (and I do not spit out my coffee lightly!).

The reason why Saunders could honestly think this hit me while reading a review of Leif Jerram’s fascinating-sounding new book, Streetlife: The Untold Story of Europe’s Twentieth Century: we have reached the end of history in the West. I don’t know why it took me so long to figure it out, given the rhetoric that has emerged from the mouths of Barrack Obama, Stephen Harper, Angela Merkel, and David Cameron during the Arab Spring and Summer, or what Dubya had to say about Iraq and Afghanistan, and what our politicians say about pretty much every tinpot dictator the world over.

We are all liberals (even the conservatives), we believe in democracy, free markets, and capitalism. We have so deeply internalised these ideas we can no longer see outside of them, or even around them. We are losing out historical consciousness. And so Saunders, who is an intelligent, thoughtful columnist for the Globe & Mail can, in all seriousness, write the phrase that made me spit out my coffee. He can’t see around liberalism. And no surprise.

So maybe we have indeed reached the end of history after all, despite the last decade of terrorism and jihadism. Maybe Fukuyama was right after all.

On Irish Historiography, Revisionism, and the Troubles

August 22, 2011 § 3 Comments

Last month, at the Annual Conference of the Canadian Association of Irish Studies at my alma-mater, Concordia University, I was witness to an interesting discussion about revisionism in Irish historiography. The discussion centred around issues of identity in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. In particular, the issue of binaries, in that one was either Protestant or Catholic and the twain never met.

I have long had problems with revisionist history (in the historiographical sense, let me be clear), in that it seeks to normalise, which means it plays down the unusual, the anachronisms, and so on. In some ways, this is a good thing. In the case of Ireland, there is some good which has come out of revisionism, most notably, we are free to focus less on the stereotypical tragic history of a “famished land, who fortune could not save” (to quote the Pogues). In short, Ireland is free to become (to borrow from revisionism in Québec historiography) “une nation comme les autres.” Revisionism also leads us to post-structuralism and allows us to get past the binaries in many ways: Catholic v. Protestant, man v. woman, city v. rural, North v. South, Ireland v. England, etc. We can see the greys now, a process begun with the muddying of the playing field by the great revisionists of the 20th century: T.W. Moody and Robert Dudley Edwards, as well as the great troubadour of revisionism of our era: Roy Foster.

But, this becomes problematic when taken too far. When we become too focussed on seeing past the binaries, to see all the ways Catholics and Protestants got along in Belfast, in Derry, and across the North, we run a new risk. And that is to trivialise the Troubles. The Troubles was, ultimately, a civil war between nationalists and unionists in Northern Ireland. For the most part, we have long used “nationalist” and “Catholic” and “Protestant” and “unionist” as synonyms. And it is good to see across the lines, to see the attempts at peace-building and community-making in the midst of the terror and devastation of the Troubles. But if we push this impulse too far, then we are blind to the Troubles (or any other conflict that relies on binaries). There is a reason that those two sets of words were/are seen synonymously. It remains that over 3,500 people are dead, countless lives were torn asunder, and the two cities of Northern Ireland, Belfast and Derry, still bear the scars of the Troubles on their landscapes.

We, as historians can try all we like to see past the binaries here, but the simple fact remains that this binary was a pretty fundamental one, it resonated with people, it caused them to fight, sometimes to the death, for what they believed in. It caused them to engage in terrorism. It tore families and communities apart. We cannot lose sight of that.

On Hatred and Continuums: DeSean Jackson and GK Chesterton

July 11, 2011 § Leave a comment

Apparently Philadelphia Eagles’ wide receiver, DeSean Jackson, said something stupid on satellite radio last week, using homophobic slurs to shut down a caller. He later apologised on Twitter, but followed that up with a stupid comment about himself being the victim of people trying to take him down, though he has since deleted that tweet and replaced it with more apologies. Big deal, right? Well, sort of. See, Jackson has done a lot of good work in the world on behalf of bullied children, and bullying a belligerent caller makes him, well, a bully and therefore a hypocrite.

But the larger issue is the gay slur. Dan Graziano of ESPN comments that this hardly makes Jackson a homophobe, it just makes him stupid. “Gay” is a multi-faceted term, and is often used as a putdown or a dismissal in much the same way “sucks” is. That doesn’t make it right, however. In fact, it makes it offensive. For sure, Jackson wasn’t thinking of the deeper significance of the slur when he used it, but the very fact that “gay” is used in a negative connotation to note something sucks is problematic. “Gay” is a negative term in this sense, and that, I would argue, connects it to homophobia, even though it might not actually be homophobic. Either way, there is a continuum here.

I read all of this this morning after having read the most recent issue of the Times Literary Supplement I have received, due to the Canada Post strike. It’s dated 10 June. Anyway, the feature review is a discussion of two recent works on G.K. Chesterton (it’s behind the Times’ paywall, so I haven’t linked it here). I am no expert on Chesterton, in fact, I have never read him, nor am I all that likely to do so in the future, so take this for what it’s worth.

In discussing Ian Ker’s new biography of Chesterton, G.K. Chesterton: A Biography, reviewer Bernard Manzo discusses the charges of anti-Semitism against Chesterton. First, let it be clear that Chesterton lived during a time when anti-Semitism was fashionable in the European and North American world. Second, anti-Semitism is anti-Semitism is anti-Semitism. Both Ker and Manzo attempt to downplay Chesterton’s anti-Semitism, to qualify it. I’m not so sure.

Both Manzo and Ker point out that Chesterton did not believe Jews to be capable of being Italian, English, French, etc., due to the simple fact that they were Jews, and that “Jews should be represented by Jews and ruled by Jews” and that they should have their own homeland. Indeed, Chesterton argued that all Christians should be Zionist, though, ironically, he also argued that no Christian should be an anti-Semite. Ironic because he was one.

Chesterton also argued that those Jews who lived in other countries should be sent to homelands, not unlike that imagined by Michael Chabon in his novel, The Yiddish Policeman’s Union. Or perhaps, more to the point, not unlike the “homelands” for black South Africans during the Apartheid era, or reserves for aboriginals in Canada, or, ghettos for Jews in Nazi Europe. But Ker (and Manzo) think that this could not have been the logical outcome for Chesterton, who was “perfectly sincere” in his suggestion that Jews be excluded from mainstream society.

Both Ker and Manzo play down this anti-Semitism, arguing that it needs to be cast in light of Chesterton’s deep abhorrence of Nazism and its vicious anti-Semitism in the years before his death in 1936. I remain unconvinced. Certainly, Chesterton’s anti-Semitism did not advocate the extreme ends of Hitler and the Nazis. But that doesn’t make it ok. It doesn’t mean that Chesterton was not an anti-Semite. Qualifications such as that made by Ker and Manzo are problematic, in that they simply point to complications of character.

Certainly, we are complicated creatures, we have internal contradictions and ambiguities, that’s what makes us human. But it should not let Chesterton off the hook anymore than noting that he lived in an era when anti-Semitism was fashionable. Daniel Jonah Goldhagen has argued that Nazism was the logical outcome of this pan-Atlantic world anti-Semitism (he is less successful in arguing Germans were complicit in the Holocaust). If this is indeed the case, then Chesterton belongs on the continuum of Atlantic world anti-Semitism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And attempts to discount it like those of Ker and Manzo are simply intellectual gymnastics and reek of intellectual dishonesty.

Globalised Montréal

May 12, 2011 § Leave a comment

In the past few years, there’s been a new trend in Montréal History and historiography that has seen us seek to place the city within a global context. This is a welcome change from our usual navel-gazing, as we sought to explain developments in Canada solely within a Canadian context. Certainly, the local context is important, but Canada did not develop in solitude. It was always a colony and nation tied into global political and economic currents, closely related to goings-on in Paris, London, and Washington. Indeed, scholars of Canadian foreign policy have long framed Canada within the North Atlantic Triangle, along with the UK and USA.

But, culturally and socially, while historians have noted the impact of British and/or American ideas in Canada, we have gone onto explain and analyse the Canadian context separate from the global. In Québec, though, perhaps due to political exigencies. Back in undergrad at UBC, Alan Greer’s masterful book, The Patriots and the People was the first study I ever read that attempted to internationalise Canadian history. In it, Greer re-cast the 1837 Patriote rebellions in Lower Canada within the revolutionary fervour that had swept Europe and the United States since the late 18th century. Seen in this light, the Parti Patriote wasn’t just a nationalist French Canadian political party, but part of an international of liberal revolutionaries that had corollaries in England, Ireland, France, the German territories, the Italian countries, the United States, and so on.

Greer’s book fit into the larger work of the revisionist Québec historians, who often sought to put Québec into a global context, both to explain the colony/province/nation’s development, as well as to give credence to Québec’s claims to nationhood. The goal was to present Québec as a nation commes les autres. Perhaps the book that had the greatest impact on me in this sense was Gérard Bouchard’s 2000 monograph, Genèse des nations et cultures du Nouveau Monde: Essai d’histoire comparée, in which Bouchard examines the development of Québec in relation to other “new world” cultures in Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. Put this way, Québec’s (and Canada’s) development from the moment of European settlement is globalised and we realise that Canada (and Québec) is not really all that unique.

This tendency to internationalise Québec seems to be continuing with a younger generation of historians. My friend and colleague, Simon Jolivet, has just published his new book, Le vert et le bleu: Identité québécoise et identité irlandaise au tournant du XXe siècle. Simon and I did our PhDs together at Concordia, and in 2006, the School of Canadian Irish Studies there hosted a roundtable discussion that looked at connections between Ireland and Québec, in large part this grew out of the work our PhD supervisor, Ronald Rudin had done early in the decade. It was probably the most dynamic and informative conference I’ve been at, as ideas flew around the table. Both Simon and I gained a lot from that conference and it is clear in both of our work.

For my part, I am interested in the Irish in Griffintown, Montréal, over the course of the 20th century. What I look at is, of course, identity, but I’m interested in the shaping of a diasporic identity amongst the Montréal Irish, one that situates the Irish of the city within the global context of the Irish around the world, as well as the links (such as they were) with Ireland itself. To do so, I make use of post-colonial theory, which seems particularly à-propos for the Irish, descendents of a colonial culture in Ireland, living in Montréal, the largest city of the French diaspora and thus necessarily a post-colonial location.

And this is what Sean Mills picks up in his brilliant new book, The Empire Within: Postcolonial Thought and Political Activism in Sixties Montreal. Mills situates Montréal within that postcolonial framework, and examines the ideas of decolonisation and colonialism within activist circles in Montréal in the 60s. The activists were heavily influenced by what was going on in the world around them, in de-colonial movements in Algeria, Tunisia, and, especially, Cuba, as well as the Caribbean in the 50s and 60s. Certainly, they were well aware of their skin colour and Canada’s place as a first-world nation. But the ambivalence of Montréal (still the economic centre of Canada in the 60s) is something Mills excels at drawing out. As the decade went on, American activists, in particular African American activists like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, became influential in the de-colonial struggle of the French Canadian majority of the city. This was further complicated by Montréal’s own black population, which also identified itself with the ideas coming out of the United States and the Caribbean. And as Montréal became a more complicated city, ethnically-speaking, to say nothing of the actions of the FLQ in October 1970, ideas of decolonisation lost their appeal.

Nonetheless, what is clear is that Montréal is a global city, one that takes its cue from its global connections as much as its local ones. Indeed, this is the basis of my next project about layers of diaspora on the urban landscape of the city. In the meantime, it also gives me a way to situate my own work on the Irish of Montréal in a larger global context.

Community in Pointe-Saint-Charles

April 29, 2011 § 3 Comments

Pointe-Saint-Charles has historically been an inner-city working-class neighbourhood. And a forgotten one, hemmed in by the industrial nature of the Lachine Canal and the Canadian National Railway tracks and train yards. The inhabitants toiled away for long hours for low wages, often without security of tenure at work. And then deindustrialisation hit the Pointe hard in the 70s and 80s. Suddenly, all the people who worked long hours for low wages couldn’t work anymore for any wages. And the Pointe’s unemployment rate shot up, reaching something like 33% by 1990. Even today, with creeping gentrification, the Pointe still has shocking pockets of poverty, high unemployment, and high reliance on social services. Each week, the food bank at St. Gabriel’s Church across the street from my flat has a long line outside it. The Mission du Grand Berger on rue Centre and the charity shop in the back of the towering Église Saint-Charles are going concerns. As is the pawn shop and the dollar stores on Centre. Wellington, the former commercial hub of the Pointe, looks like a ghost town.

In short, the Pointe is a classic, inner-city, downtrodden neighbourhood. And yet, it has one of the strongest senses of community I have ever seen in a city. And it is an inclusive community, one that welcomes all: French, English, working class, yuppies, immigrants. The lingering tension that hangs over the sud-ouest of Montréal between French and English doesn’t exist here. The tensions surrounding gentrification is also more or less absent. The block I live on is a dividing line between the yuppies and the working classes. I live on the north side, the yuppified side. And yet, everyone is friendly. This is seriously a place where you go into the dépanneur and end up having a 20-minute conversation with the shopkeeper and customers about the Habs. Where you know your neighbours.

The sense of community is deeply-rooted in the Pointe. One of the focal points is the Clinique communitaire de Pointe-Saint-Charles on rue Ash in the southern end of the neighbourhood. The Clinic was founded back in 1968 when a bunch of radical medical students from McGill came down here and were appalled by what they saw in terms of public health. My favourite story involved a young girl who said that when she went to the bathroom at home, she had to pound the floor with her shoes so that the rats didn’t bite her. So they did something. They weren’t entirely welcomed by the people of the Pointe, it must be noted. Instead of picking up their marbles and going home, instead they invited the community to get involved. The Clinic was a radical organisation, grassroots in nature, and the medical staff there made the connection between poverty, ill health, and mental health. The Clinic has had a psychiatrist on staff since 1970.

The Pointe Clinic predates Québec’s innovative CLSC (Centre local des services communitaire) system, a sort of front-line centre for health and other social services in the communities of the province. In fact, the Pointe Clinic was a model for Robert Bourassa’s Liberals when they created the CLSC system in 1974. The Pointe Clinic demanded that it’s autonomy be respected and the government left it outside of the CLSC system. Five years later, the Parti Québécois of René Lévesque was in power, and the government attempted to bring the Pointe Clinic into the CLSC system. Bad move, as the community mobilised and protested against the government’s decision. The government had no choice but to back down. Indeed, the Health Minister said: “Compte tenu de votre existence antérieure à l’implantation des CLSC, le ministère des affaires sociales a confirmé son intention de ne pas vous assimiler à ce type d’établissement mais bien de respecter la spécificité de votre organisme.”

And so the Clinic survived and thrived, as it continued to grow in terms of staff and importance in the community. Indeed, the Clinic is still run by members of the community, not the medical staff and certainly not the government. But this autonomy has not been easy to protect. Perhaps the greatest battle came in 1992, when Robert Bourassa and the Liberals were back in power. That year, the government proposed the Loi sur la santé et les services sociaux. As the Clinic explains on its website:

Le projet de loi C-120 menace la survie de la Clinique en la plaçant devant un choix qui n’en est pas un : soit la Clinique conserve sa charte d’organisme communautaire ‘privé’ et perd alors son permis de CLSC ainsi que le financement qui lui ai rattaché, soit elle devient un CLSC ‘public’ et renonce à sa charte et à son mode de fonctionnement communautaire.

Bad move, government. The community of Pointe-Saint-Charles mobilised on the streets. 600 people marched to protest the government’s plan. There was street theatre and delegations to the local and provincial politicians. Half of the adult population of the Pointe signed a petition protesting the government’s plans. The government had no choice but to back down.

A final battle in the middle of the last decade saw the Clinic brought within the larger system, but at the same time maintaining its autonomy. No one calls it the CLSC here in the Pointe. Instead, we all know it as the Clinique Communautaire de Pointe-Saint-Charles, or the Clinic.

A second branch was opened on rue Centre. One of the deepest ironies of a protest against the condofication of the neighbourhood came a couple of years ago when a condo development on Centre, next door to the CLSC went up in flames when it was still under construction. The developers returned, and rebuilt the condos. But those who suffered: the small drycleaner next door and the CLSC, which was closed for nearly a year as it attempted to recover.

The Clinic is a community centre in the Pointe, something for which the people here have every right to be proud. And because the people of the Pointe have been so successful in creating and protecting their clinic, the community here has been able to successfully protect itself from some forms of gentrification. I had the opportunity to spend a fair amount of time at the Clinic this winter due to some freaky health issues, and I was always blown away by the ways in which this community has mobilised to protect itself.

These days, the big issue is what is to become of the CNR yards at the southern end of the neighbourhood, the point for which Pointe-Saint-Charles is named. Rather than allow a bunch of condos be thrown up on the old rail yards , the Comité Action CN formed out of the Carrefour d’éducation populaire de Pointe-Saint-Charles on rue Centre to protect the community and to propose an alternative for the development of those lands. Last autumn, the Comité created a glossy publication, “Les terrains du CN de Pointe-Saint-Charles: Des proposition citoyennes.” Not wishing to be subject to expensive condos that will further alienate the residents of the neighbourhood and continue to put affordable housing out of reach, to say nothing of the pollution and noise caused by the construction condos on the site, the Comité proposes community gardens and a market, and to use the old buildings as a new community centre, as well as a housing co-operative. But before any of this happens, the Comité insists that the CN lands need to be decontaminated.

Too often I read of laments for community, or worse yet, the argument that community can only be forged by yuppies in their soul-less condos. Clearly, the Pointe says otherwise.