The Dystopian Promise of Neo-Liberalism

September 6, 2016 § 3 Comments

I spent late last week laid up with the flu. This means I read. A lot. I don’t have the patience for TV when I’m sick, unless it’s hockey. And since it’s late August, that didn’t happen. While laid up, I finished Jonathan Lethem’s early career Amnesia Moon, and also ploughed through Owen Hatherley’s The Ministry of Nostalgia. On the surface, these two books don’t have anything in common. The former is a novel set in a dystopic American future, whilst the latter is a polemic against austerity and the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom.

But both point to a golden era past. In the case of Amnesia Moon, obviously, given its dystopic future setting. And Hatherley is perplexed over the British right’s ability to control a public discourse of British history and memory.

In Amnesia Moon, the protagonist, a man named Chaos in some situations and Everett Moon in others, finds himself in Vacaville, which is actually a real place, about halfway between Sacramento and San Francisco in North Central California. In Vacaville, the residents are kept unstable by the central state: they are forced to move residences every Wednesday and Sunday. The majority of the residents work mind-numbing jobs, including Chaos’ love interest, Edie. The society is run by the gorgeous, who are featured on TV every night, parading about in an early version of reality TV. The people of Vacaville love and worship them. All of pop culture in Vacaville has been re-written to venerate the president and the ruling class. But most insidious, everything in Vacaville, for all residents, is based on ‘luck,’ a state-sponsored system based on a test administered by bureaucrats. Not surprisingly, those with the best luck are in the ruling classes. And then everyone else is organized and assigned their place in society based on their luck. Not surprisingly, our Edie has bad luck: her ex-husband has lost his mind, so she is a single mother with two children. She is also kept in place by a desperate government official, Ian Cooley, who is in love with her.

Compare this to Hatherley’s view of the United Kingdom in 2016:

We find ourselves in an increasingly nightmarish situation where an entirely twenty-first century society — constantly wired up to smartphones and the internet, living via complicated systems of derivatives, credit and unstable property investments, inherently and deeply insecure — appears to console itself with the iconography of a completely different and highly unlikely era, to which it is linked solely through the liberal use of the ‘A’ [i.e.: austerity] word.

See the similarities?

The Problem with France’s Burkini Ban UPDATED!

August 25, 2016 § 8 Comments

135_C

So 16 towns and cities in France, all on the Mediterranean Coast, have banned the so-called burkini, a body-covering garment that allows devout Muslim women to enjoy the beach and summer weather. France, of course, has been positively rocked by Islamist violence in the past 18 months or so. So you had to expect a backlash. But this is just downright stupid.

There is a historical context here (read this whole post before lambasting me, please). French society believes in laïcité, a result of the French Revolution of 1789 and the declericisation of French society and culture in the aftermath. To this end, French culture and the French state are both secularised. Religious symbols are not welcome in public, nor are the French all that comfortable with religious practice in public. Now, this makes perfect sense to me, coming as I do from Quebec, which in the 1960s, during our Revolution tranquille, also underwent a process of declericisation. Quebec adopted the French model of a secular state.

But, in Quebec as in France, not all secularism is equal. Catholic symbols still exist all over France as a product of French history, to say nothing of the grand cathedrals and more humble churches that dot the landscape. But other religious symbols, they’re not quite as welcome, meric.

Nonetheless, it is in the context of this laïcité that the burkini ban arises.

But in practice, it is something else entirely. This is racism. This is ethnocentrism. And this is stupid. Just plain stupid. French Prime Minister Manuel Valis claims that the burkini is a symbol of the ‘enslavement of women.’ The mayor of Cannes claims that the burkini is the uniform of Muslim extremism. It is neither. And the burkini bans are not about ‘liberating’ Muslim women in France. They are not about a lay, secular society. They are designed to target and marginalize Muslim women for their basic existence in France.

In the New York Times this week, Asma T. Uddin notes the problem with these bans when it comes to the European Court of Human Rights and symbols of Islam. Back in 2001, the Court found that a Swiss school teacher wearing a head scarf in the classroom was ‘coercive’ in that it would work to proselytize young Swiss children. I kid you not. And, as Uddin reports, since that 2001 decision, the Court has continually upheld European nations’ attempts to limit the rights of Muslims, especially Muslim women, when it comes to dress.

Then there was the shameful display of the police in Nice this week, which saw four armed policemen harass a middle-aged Muslim woman on the beach. She was wearing a long-sleeved tunic and bathing in the sun. The police, however, issued her a ticket for not ‘wearing an outfit respecting good morals and secularism.’ Again, I kid you not.

Laïcité is supposed to be not just the separation of church and state, but also the equality of all French citizens. Remember the national motto of the French republic: ‘liberté, éqalité, et fraternité.’ These are lofty goals. But the attempts to ban the burkini and attack Muslim women for their attire is not the way one goes about attaining liberté, nor égalité nor fraternité. Rather, it creates tiered culture, it creates one group of French who are apart from the rest. It is discriminatory and childish. And let’s not get on the subject of former French president Nicolas Sarkozy, who wants to run again, and promises to ensure that Muslim and Jewish students in the lycées eat pork.

I understand France’s concerns and fears. But attacking Islam is not the way to defeat terrorists who claim to be Muslim. It only encourages them. It is time for France to live up to its own mottos and goals. And Western feminists (and pro-feminist men) need to speak up on this topic.

UPDATE!!!!!

News comes this evening that the Deputy Mayor of Nice, and President of the Regional Council of Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, has threatened to sue people who share images of the police attempting to enforce the burkini ban on social media. I kid you not. Christian Estrosi states that the images cause harm to the police (if that is true, that is not right, of course).

It is worth pointing out that it would be very difficult for Estrosi to find legal standing to launch a lawsuit, as French law allows citizens and media outlets to publish images and videos of the police and that, without a judicial order, French police cannot seize a photographer’s camera or phone.

Resuscitating Lyndon Baines Johnson

August 8, 2016 § 3 Comments

Last week, I finally got around to reading Stephen King’s 11/22/63. I hadn’t read a Stephen King novel since I was around 16 and I discovered his early horror work: Dead Zone, Christine, Carrie, The Stand, The Shining, and Cujo. I read and devoured them, then moved on to other things. But my buddy, J-S, raved about this book. So, I humoured him, bought it, and read it. It was pretty phenomenal. I’m not really a fan of either sci-fi or alt.history, but this book was both. Time travel and a re-imagined history of the world since 1958.

The basic synopsis is that a dying Maine restaurateur, Al Templeton, convinces 35-year old, and lonely, high school English teacher, Jake Epping, to go back in time. See, Templeton discovered a rabbit hole to 1958 in his stock room. He’s been buying the same ground beef since the 1980s to serve his customers, hence his ridiculously low-priced greasy fare. Templeton went back in time repeatedly, until it dawned on him he could prevent the assassination of JFK. Templeton figures if he prevents JFK from dying, he’ll prevent Lyndon Baines Johnson from becoming president. And thus, he will save all those American and Vietnamese lives. So he spent all this time shadowing Lee Harvey Oswald, and plotting how to stop him. But then he contracted lung cancer. His time was almost up. So, he got Epping involved.

After a couple of test runs, Epping agrees. So back to 1958 in Maine he goes again, spends five years in the Land of Ago, as he calls it, under the name George Amberson. I’ll spare you the details. But, he is, ultimately successful in preventing the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy in Dealey Plaza in Dallas on 22 November 1963.

But when he returns to Maine in 2011, he returns to a dystopian wasteland. Before entering the rabbit hole back to the future, Epping/Amberson talks to the gatekeeper, a rummy. The rummy explains that there are only so many strands that can be kept straight with each trip back and each re-setting of time.

Anyway. Read it. You won’t be disappointed. I cannot speak to the series on Hulu, though. Haven’t seen it.

I found myself fascinated with this idea of preventing LBJ from becoming president. See, I’m one of the few people who think that LBJ wasn’t a total waste as president. This is not to excuse his massive blunder in Vietnam. Over 1,300,000 Americans, Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians died in that war. And the war left a long hangover on the United States that only really went away in time for the Iraq War hangover we’re currently living in.

But. LBJ wasn’t a total disaster. Domestically, he was a rather good president. He was, of course, the brain behind The Great Society. LBJ wanted to eliminate racial injustice and poverty in the United States. This led to the rush of legislation to set the record straight on these issues. We got the Civil Rights Act, Medicare, Medicaid, and a whole host of other initiatives in the fight against poverty in inner cities and rural areas. We got the birth of public television that ultimately led to the birth of PBS in 1970. Borrowing some from JFK’s Frontier ideas, the Great Society was envisioned as nothing less than a total re-making of American society. In short, LBJ was of the opinion that no American should be left behind due to discrimination. It was a lofty goal.

LBJ’s Great Society, moreover, was incorporated into the presidencies of his Republican successors, Richard Nixon and Gerald R. Ford. In other words, the Great Society met with approval from both Republicans and Democrats, to a degree anyway.

Of course, the Great Society failed. In part it failed because LBJ’s other pet project, the Vietnam War, took so much money from it. It did cause massive change, but not enough. In many ways, the rise of Donald Trump as the GOP nominee can be seen as long-term response to the Great Society. Trump has the most support from non-college-educated white people, the ones who feel they’ve been victimized by the liberal agenda. And, as the New York Times pointed out this week, Trump is really the benefactor of this alienation and anger, not the cause of it.

Nevertheless, I do take exception to the dismissal of LBJ as a horrible president based on the one glaring item on his resumé. No president is perfect, every president has massive blemishes on his record. Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed an executive order for Japanese Internment. Abraham Lincoln only slowly came to the realization that slavery had to end, and he did not really believe in the equality between black and white. I could go on.

King also makes an interesting point in 11/22/63: when Epping/Amberson returns to 2011 after preventing JFK’s assassination, he learns that the Vietnam War still happened. JFK, after all, was the first president to escalate American involvement in great numbers. And worse, the Great Society did not happen. There was no Civil Rights Act, no War on Poverty, etc. JFK, as King notes, was not exactly a champion of equal and civil rights.

Thus, as maligned as the Big Texan is by historians and commentators in general, I think it is at least partially unfair. LBJ had ideas, at least. And he was a visionary.

On Experts & Anti-Intellectualism

July 5, 2016 § 5 Comments

Nancy Isenberg‘s new book, White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, is attracting a lot of attention. No doubt this is, in part, due to the catchy title. White trash is a derogatory and insulting term, usually applied to poor white people in the South, the descendants of the Scots-Irish who settled down here prior to the Civil War, the men who picked up their guns and fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. (Oddly, the term is not really applied all that often to poor white people in the North).

I am also deeply suspicious of books that promise to tell me the “untold” or “true” story of anything. And certainly, if you asked American historians if class was an “untold story”, they’d laugh you right out of their office. But no doubt the title is due to Viking’s marketing department, not Isenbeg.

Nonetheless, I bought the book, but as I was doing so, I read some of the reviews on Amazon.The negative ones caught my eye. Most of the negative reviews were either misogynistic or anti-Semitic. But, one, by someone calling themselves Ralphe Wiggins, caught my eye:

This book purports to be a history of white trash in America. It is not. It is a series of recounting of what others have said about the lower white classes over the past 400 years. In most cases the author’s summarizations are a simple assertions of her opinion.

…

The book is 55% text, 35% references and 10% index. The “Epilog” is a mishmash of generalizations of Isenberg’s earlier generalizations.

Let us now parse Wiggins’ commentary. First, Wiggins complains that Isenberg simply summarizes “her opinion” and then generalizes her generalizations. Clearly, Wiggins does not understand how historians go about their craft. Sure, we have opinions and politics. But we are also meticulous researchers, and skilled in the art of critical thinking. The argument Isenberg makes in White Trash are not simply her “opinion,” they’re based on years of research and critical thinking.

Second, Wiggins complains that the book is 35% references and 10% index. Of course it is, it’s an academic work. The arguments Isenberg makes are based on her readings of primary and secondary sources, which are then noted in her references so the interested reader can go read these sources themselves to see what they make of them. Revealing our sources is also part of the openness of scholarship.

Wiggins’ review reminds me of Reza Aslan’s famous turn on FoxNews, where he was accused by the host of not being able to write a history of Jesus because he’s a Muslim. Aslan patiently explained to her over and over again that he was a trained academic, and had spent twenty years researching and pondering the life and times of Jesus. That was what made him qualified to write Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth.

But all of this, Wiggins’ review, Aslan’s turn on FoxNews is symptomatic of a bigger problem: the turning away from expertise. In the wake of the Brexit vote, the satirical news site “News Thump” announced that all experts would be replaced by Simon Kettering, a local at the neighbourhood pub:

Williams knows absolutely everything about any subject and is unafraid to hold forth against the received wisdom of 400 years of the scientific method, especially after four pints of Strongbow.

Amongst his many accomplishments Simon is remarkably well-informed about optimal football formations, the effects of political events on international capital and bond markets, and the best way to pleasure a woman – possibly his favourite subject.

His breadth of knowledge is all the more impressive as he doesn’t even need to bother spending ten seconds fact-checking on Google before issuing a firm statement.

As my good friend, Michael Innes, noted in response:

Yep. Personally, I’m looking forward to all the medical and public health experts at my local surgery being fired and replaced with Simon. Not to mention the car mechanics at my local garage. I’m sure with a little creative thinking (no research!!!) we can dig deeper and weed out yet more of the rot, too.

See, experts can be useful now and then. And Nancy Isenberg is certainly one, given that she is T. Harry Williams Professor of History at Louisiana State University.

Stupid Memes, Lies, and Ahistoricism

June 27, 2016 § 4 Comments

There is a meme going around the interwebs in the wake of last Thursday’s Brexit referendum and decision. This meme is American and has appeared on the FB and Twitter feeds of pretty much every conservative I know. And, like nearly all memes, it is stupid. And ahistorical.

I watched an argument unfold on a friend’s FB wall over the weekend, where one of the discussants, in response of someone trying to historicize and contextualize the EU, said that “History is irrelevant.” He also noted that history is just used to scare people. OK, then.

But this is where history does matter. The European Union is a lot of things, but it is not “a political union run by unaccountable rulers in a foreign land.” Rather, the EU is a democracy. All the member states joined willingly. There is a European Parliament in Brussels to which member states elect members directly. Leadership of the EU rotates around the member states.

And, the 13 Colonies, which rose up against the British Empire in 1774, leading to the creation of the United States following the War of Independence, were just that: colonies. The United Kingdom is not and was not a colony of Europe.

The two situations are not analogous. At all. In other words, this is just another stupid meme. #FAIL

The Five Foot Assassin

March 24, 2016 § Leave a comment

Phife Dawg, also known as Malik Taylor, died a couple of days ago. He was only 45. Phife is a hip hop legend, one of my favourite MCs of all-time. His music as a member of A Tribe Called Quest and his single solo album from 2000 have long been part of the soundtrack of my life. The Five-Foot Assassin was a perfect foil to Q-Tip’s smooth delivery, with his guttural growl and ability to drop a patois. He also wrote wicked rhymes, tougher and more menacing than Tip.

Tip was the unquestioned leader of Tribe. And eventually, egos got in the way of old friends. Phife always said that he felt especially excluded because both Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad, the DJ, had both converted to Islam and he had not. And he was largely absent from the 1996 album, Beats, Rhymes, and Life as Tip’s cousin, Consequence, was featured (why, I have no idea, he couldn’t hold a flame to Phife’s abilities). I remember buying Midnight Marauders in the fall of 1993 at Zulu Records on West 4th Avenue in Vancouver. I was with my friend, Tanya. It was one of the first CDs I ever bought. I still have it. The fall of 1993 was when I moved back to Vancouver from Ottawa, transferring to the University of British Columbia. I lived in the Mötördöme, with three other guys I didn’t know all that well. I worked with Steve at the Cactus Club (or the Carcass Club, as we called it) on Robson St. We also lived with Skippy, who had a law degree, but preferred to play in punk bands, and J., who was also in a punk band. That was the fall when I took the #22 bus to work on weekend mornings, I rode with Chi-Pig, legendary front-man of SNFU. Punk was the regular soundtrack at the Mötördöme; Fugazi and Jesus Lizard were our favourites. But we also played a lot of Fishbone and Faith No More. And when we were in reflective moods, we dropped some Tom Waits on. Skip, Steve, and J. were not fans of hip hop. But I insisted on playing Midnight Marauders as well. And when me and my main man Mike rode around Vancouver and its environs in the Mikemobile, a 1982 Mercury Lynx, Midnight Marauders was amongst the albums we rotated. I listened to the album on my long bus ride to UBC on the #9 Broadway bus.

Everytime I listen to that album, I am immediately dropped back into Vancouver in 1993. Similarly, their last album, 1998’s The Love Movement came out the year Christine and I moved to Ottawa, so she could begin law school. I had just graduated from Simon Fraser with my MA in History and would soon begin a long run at Public History Inc., which launched me back into academia. I got to Ottawa a month earlier than her. And in a small flat, in a very hot Ottawa summer, I listened to The Love Movement almost obsessively. It’s generally not regarded as Tribe’s best, but Phife’s rhymes, especially on “Find A Way” and “Da Booty,” made the album.

I got backstage at a couple of Tribe shows back in the day. I got to meet them. Phife was unfailingly the nicest, most polite dude you could imagine. He was just a genuinely nice guy. He was always humble, he also seemed kind of surprised he was a big deal.

I am listening to Midnight Marauders right now. Hip hop has lost one of the greatest MCs of all-time. And he was too young to go.

The Sartorial Fail of the Modern Football Coach

January 13, 2016 § 2 Comments

As you may have heard, the University of Alabama Crimson Tide won the college football championship Monday night, defeating Clemson 45-40. This has led to all kinds of discussion down here in ‘Bama about whether or not Coach Nick Saban is the greatest coach of all time. See, the greatest coach of all time, at least in Alabama, is Paul “Bear” Bryant, the legendary ‘Bama coach from 1957 until 1982.

Bear won 6 national titles (though, it is worth noting the claim of Alabama to some of these titles is tenuous, to say the least). Saban has now won 5 (only 4 at Alabama, he won in 2003 at LSU). I don’t particularly give a flying football about this argument, frankly. But as I was watching the game on Monday night, everytime I saw Nick Saban, I just felt sad.

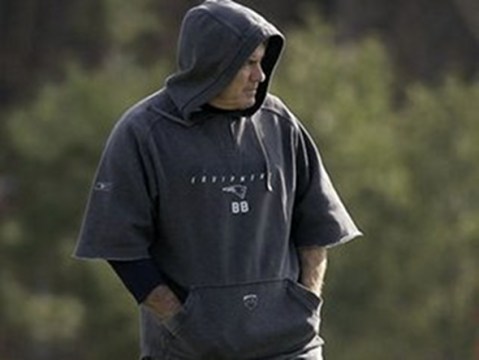

Nick Saban is a reasonably well-dressed football coach, so there is that. But, he looks like he should be playing golf. Poorly-fitting pants and and a team-issued windbreaker. He could be worse, he could be Bill Bellichk of the New England Patriots, who tends to look homeless on the sidelines.

Nick Saban is a reasonably well-dressed football coach, so there is that. But, he looks like he should be playing golf. Poorly-fitting pants and and a team-issued windbreaker. He could be worse, he could be Bill Bellichk of the New England Patriots, who tends to look homeless on the sidelines. But that’s not saying much, is it?

But that’s not saying much, is it?

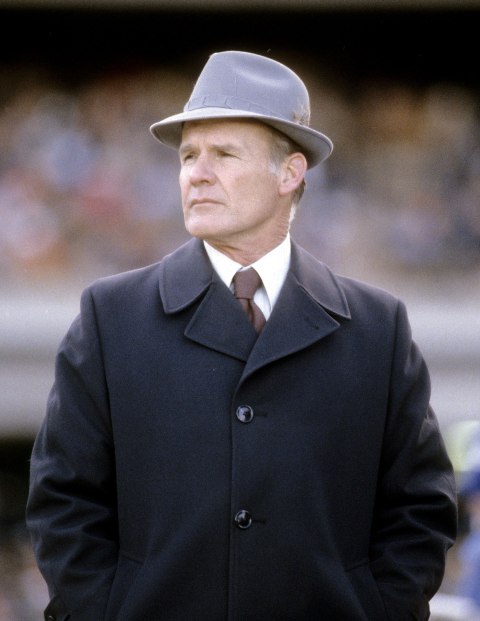

Saban and Bellichick are a far cry from Bear Bryant and Tom Landry, the legendary Dallas Cowboys coach. Bryant and Landry both wore suits on the side lines. Bryant did have an unfortunate taste for houndstooth, of course. But Landry stood tall in his suit and fedora.

There’s something to be said for looking sharp on the sidelines. I miss these well-dressed coaches.

Place and Mobility

January 8, 2016 § 7 Comments

I’m reading a bit about theories of place right now. And I’m struck by geographers who bemoan the mobility of the world we live, as it degrades place in their eyes. It makes our connections to place inauthentic and not real. We spend all this time in what they call un-places: airports, highways, trains, cars, waiting rooms. And we move around, we travel, we relocate. All of this, they say, is degrading the idea of place, which is a location we are attached to and inhabit in an authentic manner.

I see where these kinds of geographers come from. I have spent a fair amount of my adult life in un-places. I have moved around a lot. In my adult life, I have lived in Vancouver, Ottawa, Vancouver again, Ottawa again, Montreal, Western Massachusetts, Boston, and now, Alabama. If I were to count the number of flats I have called home, I would probably get dizzy.

And yet, I have a strong connection to place. I am writing this in my living room, which is the room I occupy the most (at least whilst awake and conscious) in my home. It is my favourite room and it is carefully curated to make it a comfortable, inviting place for me. It is indeed a place. And yet, I have only lived here for six months. In fact, today is six months sine I moved into this house. I have a similar connection to the small college town I live in. And the same goes for my university campus.

So am I different than the people these geographers imagine flitting about the world in all these un-places, experiencing inauthentic connections to their locales? Am I fooled into an inauthentic connection to my places? I don’t think so. And I think I am like most people. Place can be a transferrable idea, it can be mobile. Our place is not necessarily sterile. It seems to me that a lot of these geographers are also overlooking the things that make a place a place: our belongings, our personal relationships to those who surround us, or own selves and our orientation to the world.

Sure, place is mobile in our world, but that does not mean that place is becoming irrelevant as these geographers seem to be saying. Rather, it means that place is mobile. Place is by nature a mutable space. Someone else called this house home before me. This house has been here since 1948. But that doesn’t mean that this is any less a place to me.

How We Remember: Siblings and Memory

November 9, 2015 § 15 Comments

My wife and I are watching the BBC show Indian Summers. It’s about the British Raj in 1930s India and its summer retreat at Simla, in the foothills of the Himilayas. The show centres around Ralph Whelan, an orphan who has risen in the British civil service in India to become the Personal Secretary to the viceroy, as well as his sister, Alice who has mysteriously shown up in Simla, leaving behind some murkiness. Alice, you see, was married, and she claimed her husband is dead. However, it turns out he is not. I don’t know how this turns out yet, we’re only 5 episodes in.

But what interests me is the relationship between siblings. Ralph is the elder child, though it’s not entirely clear how big a difference in age there is between he and Alice. Nevertheless, it is big enough to make a huge difference in their upbringing. It’s also not clear when their parents died. Both Ralph and Alice were born in India, but Alice was sent back to England when she was 8, presumably when their parents died. She has only recently returned to the colony. Ralph, it appears, has spent most of his life in India.

The memories of Ralph and Alice of their childhood are radically different. In the first episode, Ralph manages to have dug out a rocking horse that Alice apparently loved as a child. She has no recollection of it. And this sets the pattern. Every time Ralph recalls something from their childhood, Alice responds with a blank look. At one point, she says “I didn’t have the same upbringing” as Ralph did.

I found myself thinking about the relationship between siblings and memory. Halbwachs notes the social aspect of memory, how we actually form our memories in society, not individually. In her acknowledgements to her graphic novel, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, Alison Bechdel provides a hint to the disparate memories of siblings when she thanks her family for not objecting to her publishing the book. In Fun Home, Bechdel ponders her father’s death against the discovery that he was closeted, all the while she figures out her own sexuality and comes out. Her memory of the events, and the way it is told, is carefully curated. She controls the entire story, obviously, as its her story. But, clearly, the hint is that her siblings (to say nothing of her mother) might remember things differently.

Even in my own family, largely due to the 5 1/2 years separating me from my younger sister and the 12 1/2 years between my brother and I, it often feels like we grew up in three different families. I remember things differently than my sister, and we both remember events differently than our brother does. Even events all three of us clearly remember, there are wide disparities in how we remember things go down.

As the experiences of the fictitious Whelan siblings, the real Bechdels, and me and my siblings, the existence and function of memory in a family counters Halbwachs’ claims about the formation of a collective memory. Indeed, given the strife that tends to exist in almost all families, it is clear that perhaps the formation of memories and narratives in families works differently tan in wider society.

The Myth of the ‘Founding Fathers’

November 2, 2015 § 1 Comment

Rand Paul got in trouble recently for making up quotations he attributed to the Founding Fathers. In other words, Paul is making a habit of lying to Americans, in attempting to get their votes, by claiming the Founding Fathers said something when, in fact, it’s his own policies he’s shilling. Never mind the fact that Paul says “it’s idiocy” to challenge him on this, he, in fact, is the idiot here.

The term “Founding Fathers” has always made me uncomfortable. Amongst the reasons why this is so is that the term flattens out history, into what Andrew Schocket’s calls ‘essentialism’ in his new book, Fighting over the Founders: How We Remember the American Revolution. (I wrote about this book last week, too). The term “Founding Fathers” presumes there was once a group of men, great men, and they founded this country. And they all agreed on things.

Reality is far from this. The American Revolution was an incredibly tumultuous time, as all revolutions are. Men and women, fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, brothers, sisters, disagreed fundamentally about a multitude of issues, not the least of which was whether or not independence was a good idea or not. Rarely taught in US history classes at the high school or university level, loyalists, at the end of the War of Independence, numbered around 15-20% of the population. And there is also the simple fact that less than a majority actively supported independence, around 40-45%. The remaining 35-45% of the population did its best to avoid the war or independence, for a variety of reasons.

The Constitutional Congress, then, did not speak for all the residents of the 13 Colonies, as many Americans seem to believe. The Articles of Confederation and the Constitution were fraught affairs, with many of the men involved in their drafting in staunch opposition to each other. Aside from ego, there were deep, fundamental differences in thought. In other words, the Constitution was a compromise. The generation of men (and the women who influenced them, like Abigail Adams) who created the United States were very far from a unified whole, whether in terms of the larger population, or even within the band of men who favoured and/or fought for independence.

Thus, the term “Founding Fathers” is completely inadequate in describing the history of this country between c. 1765-1814. But, then again, most Americans tend to look back on this period in time and presume a single ethnicity (British) and religion (Protestantism) amongst the majority of residents of the new country. In fact, it is much more complicated than that, and that’s not factoring in the question of slavery.

It’s not surprising that Americans would wish a simple narrative of a complex time. Complexity is confusing and it obfuscates even more than it shows. And clearly, for a nation looking at its founding myths, complexity (or what Schocket would call ‘organicism’) is useless. You cannot forge myths and legends out of a complicated debate about independence, government, class, gender, and race. It’s much simpler to create a band of men who looked the same, talked the same, and believed the same things.

But, such essentialism obscures just as much as complexity does when it comes time to examine the actual experience of the nascent US during the Revolution. The disagreements and arguments amongst the founders of the country are just as important as the agreements. The compromises necessary to create a new country are also central. I’m not really a big believer in historical “truths,” nor do I think facts speak for themselves, but we do ourselves a disfavour when we simplify history into neat story arcs and narratives. Unlike Schocket, I do think there is something to be gained from studying history, that there are lessons for our own times in history, at least to a degree: the past is not directly analogous to our times.

Of course, as a public historian, this is what I love to study: how and why we re-construct history to suit our own needs. So, perhaps I should applaud the continuing need for familiar tropes and storylines of the founding of the US.