Nothing Says Cluelessness Quite Like Joking About Gentrification

November 30, 2017 § 4 Comments

Gentrification is a topic I have written a lot about here (for example, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and, finally, here). And, of course, I wrote a book about Griffintown, Montreal. In other words, I think about gentrification a lot, occasionally curious about it, occasionally appalled by it.

Last week, a Denver coffee chain found itself in the midst of a firestorm over a really stupid sandwich board sign outside of its outlet in Five Points neighbourhood. Of course, the name Five Points carries with it various derogatory ideas, largely connected to the original Five Points in Manhattan, so the gentrifiers of Denver’s Five Points have re-christened it RiNo (or, River North Arts District). The Five Points ink! coffee shop placed this sandwich board outside its shop:

Ok, then. A few things to note. First, the sign is on dirt/gravel, next to what looks like a new(-ish) sidewalk). So clearly, gentrification is apace here. Second, Five Points is historically home to pretty much the entirety of Denver’s African American population. And, as anyone who knows anything about urban history will tell you, this also means that the congregation of the black population of the city here was not entirely always by choice. And, of course, who loses in the gentrification of traditionally African American neighbourhoods? African Americans, of course.

Third, the gentrifiers want this neighbourhood to be a centre for the arts. Not surprisingly, the arts that are native to Five Points are not all that welcome in the newly re-imagined RiNo. Why? Because hip hop is still seen as a black art form, and that makes a lot of white people uneasy, even today after hip hop has gone global.

And while the people at ink!’s Five Points shop may have thought they were being edgy and funny, they were not. They were being stupid. And offensive. Yes, gentrification usually means you can get good coffee in your neighbourhood, but at what cost? And who benefits from gentrification in the US? The answer to the latter question is predominately white, young, urbanites with well-paying jobs.

And that means that those who lose from gentrification are people who do not look like them, these urban explorers. Gentrification is, I think, as close to an inevitable process as we have. But, that doesn’t mean that it needs to be brainless and lead to the displacement of the residents, and it doesn’t need to mean a whitewashing of neighbourhoods traditionally of colour.

And to joke about this whitewashing? Well, that’s frankly offensive and stupid. And Keith Herbert, the founder of ink!, comes across as especially daft in his Twitter statement, but at least he’s trying. That’s something, I guess:

The True North Strong and Free

November 6, 2017 § 2 Comments

Last week, Canadian Governor General Julie Payette gave a speech at what the Canadian Broadcast Corporation calls ‘a science conference‘ in Ottawa. There, she expressed incredulity in creationism and climate change denial, and called for a greater acceptance of scientific fact in Canada. Payette is a former astronaut, holds an MSc in computer engineering, and has worked in the field of Artificial Intelligence. In other words, when she speaks on this matter, we should listen.

Her comments ignited a storm of controversy in Canada. Some people are upset at her comments. Some people are upset the Governor General has an opinion on something. With respect to the first, Payette spoke to scientific fact. Full stop. Not opinion. Fact. With respect to the second, Governors General and opinions, I will point out that our former Governor General, David Johnston, also freely expressed his opinions. But, oddly, this did not lead to massive controversy. What is the difference between Payette and Johnston? I’ll let one of my tweeps, author Shireen Jeejeebhoy answer:

But then I found a particularly interesting tweet. The tweet claimed that for the very reason that Canada has the monarchy, the country cannot have democratic elections.

Um, what? There is no logic to this tweet. I asked the author of the tweet what he meant. In between a series of insults, he said that he thinks the Governor General, which he mistakenly called an ‘important position,’ should be an elected post. That gives some clarity to his original post, but he’s still wrong.

Canada is a democracy, full stop. Elections in Canada are democratic, full stop.

Canada is a constitutional monarchy. Queen Elizabeth II is the Head of State. The Governor General is her representative in Canada (each province also has a Lieutenant-Governor, the Queen’s representatives in the provincial capitals). The Queen does appoint the GG (and Lt-Govs), but she does so after the prime minister (or provincial premiers) tell her who is going to be appointed. In other words, Payette has her position because Prime Minister Justin Trudeau selected her.

Canada, unlike the United States, did not gain ‘independence’ in one fell swoop. In 1848, Queen Victoria granted the United Province of Canada, then a colony, responsible government. This gave it (present-day Ontario and Québec) control over its internal affairs. All legislation passed by the colonial assembly would gain royal assent via the Governor General. Following Confederation in 1867, the new Dominion of Canada enjoyed responsible government (which the other colonies that became Canada also had). But Canada did not control its external affairs, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and (Northern) Ireland did. In 1931, the British Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster, which granted control over foreign affairs to the Dominions (Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand). In 1947, Canadian citizenship was created. Prior to that, Canadians were subjects of the monarchy. In 1949, the Supreme Court of Canada became the highest court in the land. Prior to that, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London was. In 1982, the Canadian Constitution, which had been an act of the London Parliament (the British North America Act, 1867) was patriated and became an act of the Parliament in Ottawa. So, choosing when Canada became independent is dicey. You can pick anyone of 1848, 1931, 1947, 1949, or 1982 and be correct, at least in part. We tend to celebrate 1867, our national holiday, July 1, marks the day the BNA Act came into affect. That is the day Canada became a nation, but it is not the date of independence.

Either way, Canada is an independent nation. Lamarche’s claim that, because we are a constitutional monarchy, we do not have free elections is ridiculous. The role of the monarchy in Canada is entirely symbolic. The Queen (or the Governor General or Lieutenants Governors) have absolutely no policy input. They have no role in Canadian government beyond the symbolic. None.

I’m not even sure how someone could come to this conclusion other than through sheer ignorance.

A History of Globalization

October 31, 2017 § Leave a comment

I read Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others last week. For some reason, Sontag has always loomed on the fringes of my cultural radar, but I had never read anything by her, other than a few essays or excerpts over the years. In some ways, I found her glib and in others, profound. But I also found her presentist.

At the start of the second chapter, she quotes Gustave Moynier, who in 1899, wrote that “We know what happens every day throughout the whole world,” as he goes onto discuss the news of war and calamity and chaos in the newspapers of the day. Sontag takes issue with this: “[I]t was obviously an exaggeration, in 1899, to say that one knew what happened ‘every day throughout the whole world.'”

We like to think globalization is a new phenomenon, that it was invented in the past 30 years or so and sped up with the advent of the internet and, especially social media, as we began to wear clothes made in China, rather than the US or Canada or Europe. Balderdash. Globalization has been underway since approximately forever. Europeans in the Ancient World had a fascination with the Far East, and trade goods slowly made their way across the Eurasian landmass from China to Italy and Greece. Similarly, the Chinese knew vaguely of the faraway Europeans. In the Americas, archaeological evidence shows that trade goods made their way from what is now Canada to South America, and vice versa. Homer describes a United Nations amassing to fight for the Persian Empire against the Greeks.

Trade has always existed, it has always shrunk the world. Even the manner in which we think of globalization today, based on the trade of goods and ideas, became common place by the 18th century through the great European empires (meanwhile, in Asia, this process had long been underway, given the cultural connections between China and all the smaller nations around it from Japan to Vietnam).

For Sontag, though, her issue is with photographs. Throughout Regarding the Pain of Others, she keeps returning to photographs. She is, of course, one of the foremost thinkers when it comes to photographs, her landmark On Photography (1977) is still highly regarded. In many ways, Sontag seems to believe in the credo ‘pics or it didn’t happen.’

Thus, we return to Moynier and his claim to know what was going on in the four corners of the world in 1899. Sontag, besides taking issue with the lack of photographs, also calls on the fact that ‘the world’ Moynier spoke of, or we see in the news today, is a curated world. No kidding. But that doesn’t make Moynier’s claim any less valid than the New York Times’ claim to ‘print all the news that’s fit to print.’ That is also a carefully curated news source.

In Moynier’s era, Europeans and North Americans, at least the literate class, did know what was happening throughout the world. The columns of newspapers were full of international, national, and local news, just like today. And certainly, this news was curated. And certainly, the news tended to be from the great European empires. And that news about war tended to be about war between the great European empires and the colonized peoples, or occasionally between those great European empires. But that doesn’t make Moynier’s claim any less valid. He did know what was going on around the world. He just didn’t know all that was going on. Nor do I today in 2017, despite the multitude of news sources available for me. The totality of goings on world wide is unknowable.

And Sontag’s issue with Moynier is both a strawman and hair-splitting.

Staging the Civil War

October 26, 2017 § Leave a comment

‘Everyone is a literalist when it comes to photographs,’ Susan Sontag wrote in Regarding the Pain of Others. She has a point, sort of. We expect photographs to represent reality back to us. But they don’t, of course, or they don’t necessarily. For example, she discusses an exhibit of photographs of September 11, 2001, that opened in Manhattan in late September of that year, Here is New York. The exhibit was a wall of photographs showing the atrocity of that day. The organizers received thousands of submissions, and at least one photo from each was included. Visitors could chose and purchase a laser printed version of a photo, but only then did they learn whether it was a photo from a professional or an amateur hanging out their window as the atrocity occurred. Sontag talks about the fact that none of these photos required captions, the visitors will have known exactly what they depicted. But she also notes that one day, the photos will require captions. Because the cultural knowledge of that morning will disappear. 9/11 is already a historical event for today’s young adults.

So we return to the veracity of photos, our expectation of a documentary image of the past. For me, the first time I was seriously arrested by a photograph was in my Grade 12 history textbook, in the section on the Second World War. There was a photograph of an American soldier lying dead on a beach somewhere in the Pacific. I don’t remember where or which battle. I don’t remember the image all that well, actually, I don’t think the viewer could see the soldier’s face. I remember just a crumpled body, in black and white. And for the first time, I understood the devastating power of war and the fragility of the human body.

Later, in grad school, I read Ian McKay’s The Quest of the Folk, about how Nova Scotia’s Scottish history was carefully constructed and curated by folklorists at the turn of the 20th century. At the start of the book is a photograph of a family next to their cottage on a hard scrabble stretch of land on the Cape Breton coast. McKay plays around with captions of the photo, both the official one in the Nova Scotia archives in Halifax, and alternative ones. I realized that photographs are not really necessarily a true and authentic vision of the past.

And so, in reading Sontag’s words I opened this essay with, I thought of the fact that we do like to think of ourselves as literalists when it comes to photography, we expect a ‘picture to say a thousand words,’ and so on. Just prior to this comment, Sontag discussed Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War, a series of plates that weren’t published until several decades after Goya’s death. The disasters were the Napoléonic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 1808. These plates are vicious. And Goya narrates each, claiming each one is worse than the other, and so on. He also claims that this is the truth, he saw it. Of course, they aren’t the documentary truth, they instead represent the kinds of events that happened. That does not, however, lessen their power and brutality. But they are also not photographs.

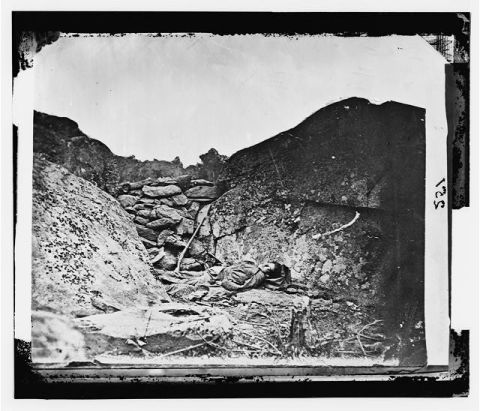

This led me to Alexander Gardner, the pre-eminint photographer of the US Civil War. In fact, war photography in general owes a huge debt to Gardner. Gardner worked for the more famous Mathew B. Brady, but it was Gardner who took the majority of the more famous photographer’s photos. Gardner shot some of the most iconic images of the Civil War, including the dead at Gettysburg. His most famous is this one:

Photo taken from the Library of Congress’s website

This photograph is staged. Gardner and his assistants dragged the body of this dead Confederate soldier from where he fell to this more photogenic locale. They also staged his body. And yet, given our insistence on literalism in photography, the viewing public took this photo for what it’s worth and accepted it as a literal representation of the Battle of Gettysburg.

It was over 100 years later, in 1975, when a historian, Willian Frassantino, realized that all was not as it seems. Of course, what Gardner, et al. did in staging the photos of the Civil War seems abhorrent to us, unethical, even. But it was not so in the mid-19th century at the literal birth of this new medium of representation.

Nonetheless, what is the lesson from Gardner’s photograph? Do we dismiss it for its staginess? Do we thus conclude that the photos of the Civil War are fake? Of course not. Gardner’s photos, like Goya’s Disasters of War, are representations of what happened. They are signifiers that things like this happened (I am paraphrasing Sontag here). It does not make these representations any less valuable. Young men did die by the thousands in the Civil War. They died at places like Gettysburg, and they died like the staged body of this unfortunate soul. The horrors of war remain intact in our minds. We have a representation of what happened, and this one in particular (like Goya’s Disasters) has been replicated countless times since 1863, we have seen countless other images like this, including for me, the one in my Grade 12 history textbook when I was all of 17 years of age. The image is still real.

#MeToo: A Public Service Announcement

October 17, 2017 § Leave a comment

Since around Sunday afternoon, women have been posting on social media that they have been victims of sexual assault and/or sexual harassment. My Twitter and Facebook feeds are full of these brave posts, with the hashtag #MeToo. But, almost immediately, the backlash came. From men.

Yes, men are the victims of sexual assault, too. Around 10% of rape victims are male, and around 3% of men in the United States have been sexually assaulted. This is a very real problem. And the sexual assault of men does not get much coverage in our world. To be a male survivor of sexual assault is alienating and lonely. In fact, many of the same things women experience, men experience in the aftermath of being sexually assaulted.

But. This male backlash to #MeToo smacks of an attempt to deny women their experiences. It also smacks of ‘All Lives Matter.’

A couple of years ago, at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, white conservatives began the counterpoint: All Lives Matter. Well, duh. Of course all lives matter. That was never open for debate. No one ever said that because Black Lives Matter, other lives don’t. But the simple fact was that the discussion was about black lives, which were much more likely to be terminated at the hands of the police than other types of lives.

In effect, saying ‘All Lives Matter’ was an attempt to equate the African American experience with the white American experience, and to say they were both equal. They’re not. This nation was founded upon exploiting the labour and bodies of African Americans, and even though slavery ended 152 years ago, the cost for black bodies has not ended. And even though the Civil Rights Era was half a century ago, the cost for black bodies has not ended. To suggest the white and black experience is the same is a false equivalence.

Not all men who are speaking out right now are attempting to deny women’s experiences. They are speaking out of of the same, or similar place. But, this is already being used to silence women. Some men are using these men’s experiences to claim an equivalence of the male and female experience. This is already being used to deny the experience of women. A few years ago, during another heightened consciousness over the experience of women, #YesAllWomen was a social media activist campaign. Because almost all women have experienced this. So, to claim that the male and female experience of sexual violence is the same is wrong. It is not. It is a false equivalence.

Double Standards and False Equivalencies

October 12, 2017 § 1 Comment

Harvey Weinstein is disgusting. At the very least, he is guilty of being a lecherous, disgusting man. At the worst, he’s a rapist. His defence of coming-of-age in the licentious 1960s and 70s is bullshit. Many men came of age then, and they don’t commit sexual assault. Nor is Weinstein alone, I’m sure. As my friend Matthew Friedman noted, he is certainly not the only Hollywood mogul who used his power to bully young women into places they didn’t want to go, to use his power to sexually abuse them. Think of the long-standing and endless jokes about casting couches and the like. Weinstein just got caught. After 40 years. In many ways, Weinstein is like the president, who, of course, boasted on tape for Access Hollywood, how he commits sexual assault. As Marina Fung noted in the Huffington Post, the Weinstein tape is the sequel to the Trump tape. And, of course, let us not forget last year’s scandal in Canada, where Jian Ghomeshi was accused of similar things as Weinstein and walked. And then, of course, there is Bill Cosby.

Make no mistake, Weinstein, Trump, Ghomeshi, and Cosby are just the tip of the iceberg. And thus far, there have been no criminal consequences for any of these men. Hell, Donald Trump was elected president. Weinsten, Ghomeshi, and Cosby have lost their good reputations, so there’s that. But that doesn’t really amount to much.

Republicans, of course, are having a field day with Weinstein, especially because he is such a huge donor to Democratic Party causes. And he donated to Hillary Clinton’s campaign last year (and Barack Obama’s in 2008 and 2012, and John Kerry’s in 2004, and Al Gore’s in 2000, and Bill Clinton’s in 1992 and 1996, and so on). A lot of conservatives are calling Hillary Clinton to account for Weinstein (and her husband, and Anthony Weiner). And even some progressives are calling on her to account for Weinstein (and her husband and Anthony Weiner, and Donald Trump).

This is also bullshit. It is also creating a false equivalence. Hillary Clinton has nothing to account for when it comes to Weinstein, nor do Democrats in general. What Weinstein did is downright reprehensible, as I’ve made clear. But he is one (formerly powerful) man. She has nothing to do with what he did. Nor does she have anything to do with what Anthony Weiner did.

We can start with the hypocrisy of conservatives demanding Hillary Clinton account for Weiner when they refuse to for Donald Trump. But we can go further. Calling out Hillary Clinton is just further proof of the sexism and misogyny in our culture. It is further proof of the way in which our culture (and I mean the totality of our culture, progressives, centrists, and conservatives) holds women to a double standard.

It is bad enough that Harvey Weinstein violated countless young women. It is worse that our culture expects the female Democratic Party candidate for President in 2016 to account for this disgustingness.

Harm Reduction in Drug Addiction

August 4, 2017 § Leave a comment

The opioid crisis that has taken root across North America exposes several ugly truths. The first is racial. The use of drugs is treated differently in the United States, depending on the race of the victims of addiction. When they are African American and/or Latinx, they are criminalized. But when it is white people using drugs, it becomes a crisis. To a degree. The important disclaimer here is class. When poor white people are using, it remains a criminal issue. But when middle- or upper- class white people are using, it becomes a public health issue. Thus, this is the second truth: class.

I think of all the jokes I have heard about ‘white trash’ and meth labs in trailer homes since I moved to the South. But, on the flip side, there is the criminalization and demonization of poor white people, and nearly all African American and Latinx drug addicts. Addiction, I remind, is a public health issue. Addiction is a question of psychology. It is not a matter of criminality.

Addiction is something very real in my world. It is something I grew up with in my family. When I was a university student in Vancouver in the early-to-mid-90s, the city was in the midst of a heroin epidemic. Walking through the fringes of the Downtown Eastside one afternoon, I passed the back alley on Carrall St., between East Hastings and East Pender, and saw a young woman, around my age, with a needle in her arm, foaming at the mouth and her fingertips going blue. There was no one around. And she was dying. I went into the alley, she was unresponsive, and her pulse was very faint. There was no one around. No police, no other pedestrians on Carrall St. All the doors in the back alley were closed, some of them barred from the outside. There was no one looking out the windows onto the alley. She was completely alone. And then she died. I don’t know how many people died in Vancouver of heroin overdoses in 1997. But I know she was someone’s daughter, sister, grand-daughter, girlfriend. I did find a police patrol on East Pender about two blocks away, and I told them. I told them everything I saw. I was very shaken, of course. I went home, they went to the back alley to deal with her body.

Vancouver is the site of a long-term heroin crisis. This crisis has been made worse by the addition of fetanyl to nearly every drug on the market on the West Coast. My mother is an addictions counsellor in Vancouver. Every time I talk to her, she says that her recovery centre has lost 2, 3, 4, 5, or more, guys in the past week or however long it has been since I last talked to her. Nonetheless, at least Vancouver has engaged in harm-reduction, which at the very least, makes it safer for heroin addicts, in terms of needle exchanges and safe-places for injection.

Vancouver is home to the only heroin-injection clinic in North America. It has been in operation for eight years now, operates at capacity (130 people, only a fraction of the addicts on the streets of the Downtown Eastside of the city), and is controversial, not surprisingly. In 2013, the then-Health Minister, Rona Ambrose, tried to shut it down, claiming that it enabled addicts. But it survived.

In Gloucester, Massachusetts, a sea-side town about an hour north of Boston, police there decided to begin treating the opioid crisis as a public health issue in May 2015. Police Chief Leonard Campanello notes, as many others have, that there has been a failure to stem the flow of illegal drugs into the country (be it Canada or the US), and that, ultimately, we have lost the war on drugs. Campanello thinks, rather, that it’s a war on addiction.

The important thing to note in both Vancouver and Gloucester is that the police and other agencies there treat addicts as human beings in crisis. And they treat all addicts as such, class and race are not part of the calculus. And Vancouver and Gloucester are just two examples of many across both the United States and Canada where jurisdictions have sought to treat addiction as a public health issue in order to engage in harm reduction.

Last month, in Philadelphia, news broke that the staff at the public library branch on McPherson Square in the Kensington neighbourhood had become first-line responders to heroin overdoses in the park. Several times a day, librarians were rushing out to administer Narcan to people overdosing. Volunteers scoured the park daily for used needles and other paraphernalia of addiction. Librarians referred to the addicts out in the park as ‘drug tourists,’ as Philadelphia, as a port city, has a particularly pure form of heroin on its streets.

But, within a couple of weeks, McPherson Square was nearly devoid of addicts. The police had descended onto the park and pushed them away. Thus, the addicts were back in the shadows, living and shooting up in abandoned homes, in back alleys, hiding in the dark corners of the city. And while some community organizations continued their work of trying to help the addicts, it appears that the police in Philadelphia have not turned to a new model, but, rather, to the old model of scaring off drug addicts, criminalizing them and sending them into the shadows.

I don’t think there is anything new or revelatory in what I’ve said here. Drug addiction is a public health crisis, first and foremost. Harm reduction in locations like Vancouver and Gloucester have made a difference, they have made positive changes in addicts’ lives, including saving lives and getting people off the streets. And harm reduction programmes have got addicts into rehab and off drugs entirely. The criminalization of drug addicts does not have such results.

More to the point, society’s response to drug addiction amongst marginal populations (poor white people) and ethnic and racial minorities (marginalized in their own ways) speaks to how we see some people as disposable. The morality of such a view is beyond my comprehension, it is something I just fundamentally do not understand.

On Photography and Filtering

October 24, 2017 § 5 Comments

A few weeks ago, I posted this picture on Instagram. Immediately, my more smart-arsed friends began to chatter. I used the hashtag #nofilter, meaning that I did not use an Instagram filter. Not good enough for the commentariat, though. They commented on the mental filters, frame filters, and so on as I framed the photo and so on. They’re not wrong. (The photo, if you are wondering, is of a creek about a mile from my home in Western Massachusetts).

Of course this photo was filtered, from the way the creek caught my eye as I walked the dogs, to the way I framed the photo as I took it, choosing what to get into the photo and what to leave out. All photos are filtered and framed. Duh. I’ve been mulling over this since.

Then I saw the obligatory article in the Washington Post about where to go to see fall foliage colours. The first photograph in the article is from another locale in New England, Albany, NH. It’s a stunning photo of rushing water and brilliant reds. Meanwhile, my friend Matthew Friedman has been running around New York and New Jersey with a real camera of late, taking some absolutely stunning photos that he develops himself, as he is a man of many skills. Taken together with my apparent addiction to Instagram, a lightbulb went off in my head when I posted this picture in my feed:

This is a heavily filtered and edited photo showing the brilliant autumn colours on my street. But notice how the oranges and yellows and greens, and the auburn of the dead leaves, pop in this photo. Not unlike the reds of the leaves and the white of the rushing waters in the photo from Albany, NH, in the Post article.

The differences between the heavily edited and filtered photo I posted and the original are striking, I think.

This is still a beautiful shot, I think. But the colours aren’t as gripping, they don’t pop. And the lighting is much darker than in my Instagram post. So what did the original of the Albany, NH, photo in The Post look like? I presume Jim Cole, the AP photographer, shot it with a digital camera and ended up with an original that looks like mine. But then he edited it with editing software until the reds and yellows of the leaves and the white of the rushing water and the blacks of the stones in the river popped like that. The photo is glossy. And it’s beautiful. It’s an arresting image, and it is no surprise it is the lead photo in the article.

Photography as we think about it is filtered and edited, oftentimes heavily. It is often also staged. Or consider the fact that Robert Doisneau’s famous photos of lovers kissing outside Hôtel de Ville in Paris was staged. This is one of the most iconic photos of all-time, and has been used for any range of purposes, almost all of which have to deal with the romanticization of Paris. But these were not two lovers. They were two models Doisneau hired for the day. Does that lessen the impact of the photo? No. It doesn’t. In fact, Doinseau was unapologetic, noting that he did not photograph life as it is, but as we wish it to be.

So, yes. Almost ALL photos are filtered, beyond the mental filters and the framing of the photo. They are filtered via the production process, whether in a darkroom as Doisneau and Friedman work, or digitally, as Cole and I have done.

Kind of obvious, no?