Harm Reduction in Drug Addiction

August 4, 2017 § Leave a comment

The opioid crisis that has taken root across North America exposes several ugly truths. The first is racial. The use of drugs is treated differently in the United States, depending on the race of the victims of addiction. When they are African American and/or Latinx, they are criminalized. But when it is white people using drugs, it becomes a crisis. To a degree. The important disclaimer here is class. When poor white people are using, it remains a criminal issue. But when middle- or upper- class white people are using, it becomes a public health issue. Thus, this is the second truth: class.

I think of all the jokes I have heard about ‘white trash’ and meth labs in trailer homes since I moved to the South. But, on the flip side, there is the criminalization and demonization of poor white people, and nearly all African American and Latinx drug addicts. Addiction, I remind, is a public health issue. Addiction is a question of psychology. It is not a matter of criminality.

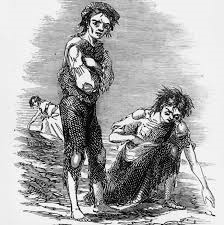

Addiction is something very real in my world. It is something I grew up with in my family. When I was a university student in Vancouver in the early-to-mid-90s, the city was in the midst of a heroin epidemic. Walking through the fringes of the Downtown Eastside one afternoon, I passed the back alley on Carrall St., between East Hastings and East Pender, and saw a young woman, around my age, with a needle in her arm, foaming at the mouth and her fingertips going blue. There was no one around. And she was dying. I went into the alley, she was unresponsive, and her pulse was very faint. There was no one around. No police, no other pedestrians on Carrall St. All the doors in the back alley were closed, some of them barred from the outside. There was no one looking out the windows onto the alley. She was completely alone. And then she died. I don’t know how many people died in Vancouver of heroin overdoses in 1997. But I know she was someone’s daughter, sister, grand-daughter, girlfriend. I did find a police patrol on East Pender about two blocks away, and I told them. I told them everything I saw. I was very shaken, of course. I went home, they went to the back alley to deal with her body.

Vancouver is the site of a long-term heroin crisis. This crisis has been made worse by the addition of fetanyl to nearly every drug on the market on the West Coast. My mother is an addictions counsellor in Vancouver. Every time I talk to her, she says that her recovery centre has lost 2, 3, 4, 5, or more, guys in the past week or however long it has been since I last talked to her. Nonetheless, at least Vancouver has engaged in harm-reduction, which at the very least, makes it safer for heroin addicts, in terms of needle exchanges and safe-places for injection.

Vancouver is home to the only heroin-injection clinic in North America. It has been in operation for eight years now, operates at capacity (130 people, only a fraction of the addicts on the streets of the Downtown Eastside of the city), and is controversial, not surprisingly. In 2013, the then-Health Minister, Rona Ambrose, tried to shut it down, claiming that it enabled addicts. But it survived.

In Gloucester, Massachusetts, a sea-side town about an hour north of Boston, police there decided to begin treating the opioid crisis as a public health issue in May 2015. Police Chief Leonard Campanello notes, as many others have, that there has been a failure to stem the flow of illegal drugs into the country (be it Canada or the US), and that, ultimately, we have lost the war on drugs. Campanello thinks, rather, that it’s a war on addiction.

The important thing to note in both Vancouver and Gloucester is that the police and other agencies there treat addicts as human beings in crisis. And they treat all addicts as such, class and race are not part of the calculus. And Vancouver and Gloucester are just two examples of many across both the United States and Canada where jurisdictions have sought to treat addiction as a public health issue in order to engage in harm reduction.

Last month, in Philadelphia, news broke that the staff at the public library branch on McPherson Square in the Kensington neighbourhood had become first-line responders to heroin overdoses in the park. Several times a day, librarians were rushing out to administer Narcan to people overdosing. Volunteers scoured the park daily for used needles and other paraphernalia of addiction. Librarians referred to the addicts out in the park as ‘drug tourists,’ as Philadelphia, as a port city, has a particularly pure form of heroin on its streets.

But, within a couple of weeks, McPherson Square was nearly devoid of addicts. The police had descended onto the park and pushed them away. Thus, the addicts were back in the shadows, living and shooting up in abandoned homes, in back alleys, hiding in the dark corners of the city. And while some community organizations continued their work of trying to help the addicts, it appears that the police in Philadelphia have not turned to a new model, but, rather, to the old model of scaring off drug addicts, criminalizing them and sending them into the shadows.

I don’t think there is anything new or revelatory in what I’ve said here. Drug addiction is a public health crisis, first and foremost. Harm reduction in locations like Vancouver and Gloucester have made a difference, they have made positive changes in addicts’ lives, including saving lives and getting people off the streets. And harm reduction programmes have got addicts into rehab and off drugs entirely. The criminalization of drug addicts does not have such results.

More to the point, society’s response to drug addiction amongst marginal populations (poor white people) and ethnic and racial minorities (marginalized in their own ways) speaks to how we see some people as disposable. The morality of such a view is beyond my comprehension, it is something I just fundamentally do not understand.

Equalization Payments in Canada

July 31, 2017 § Leave a comment

Over the weekend on Twitter, I was caught up in a discussion with an Albertan who didn’t believe that the province, along with British Columbia, is forecast to lead Canada in economic growth.

She argued that the province is still hurting, that big American gas companies had pulled out, and that people were leaving Alberta. Indeed, in June, Alberta’s unemployment rate was 7.4%, but even then, that was an improvement of 0.4% from May. But, economic growth does not mean that one can necessarily see the signs of a booming economy. Alberta’s economy, however, shows signs of recovery, and this 2.9% economic growth, as well as a decline in unemployment rates, shows that.

She also expressed a pretty common bitterness from Albertans about Equalization payments in Canada. These payments might be the most mis-understood aspect of Canadian federalism. The common belief in Alberta, which is usually a ‘have’ province (meaning it doesn’t receive equalization payments), is that its money, from oil and gas and everything else, is taken from it and given to the ‘have-not’ provinces (those who receive equalization payments). This is made all the more galling to Albertans because Quebec is the greatest recipient of equalization payments.

This argument, though, is based on a fundamental mis-understanding of how equalization payments work in Canada. Equalization payments date back to Canadian Confederation in 1867, as most taxation powers accrued to the federal government. The formal system of equalization payments dates from 1957, largely to help the Atlantic provinces. At that time, the two wealthiest provinces, Ontario and British Columbia, were the only two ‘have’ provinces. And this formal system was enshrined in the Constitution in 1982. Section 36, subsection (2) of the Constitution Act reads:

Parliament and the government of Canada are committed to the principle of making equalization payments to ensure that provincial governments have sufficient revenues to provide reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation.

The general idea behind equalization payments is, of course, that there are economic disparities across the nation. There is any number of reasons for these disparities, which are calculated on a provincial level. These can include the geographic size of a province, population, the physical geography, or economic activity.

Quebec is a traditional ‘have not’, which seems incongruous with the size and economy of the province. Montreal, after a generation-long economic decline from the late 1960s to the mid 1990s, has more or less recovered. If Quebec were a nation of its own (as separatists desire), it would be the 44th largest economy in the world, just behind Norway. It contributes 19.65% of Canada’s GDP. But Quebec’s economy is marked by massive inequalities. This is true in terms of Montreal versus much of the rest of the province. But it is also true within Montreal itself. Montreal is home to both the richest neighbourhood in the nation, as well as two of the poorest. Westmount has a median family income of $220,578. But Downtown Montreal ($32,841) and Parc Ex ($34,211) are the fourth and fifth poorest, respectively, in Canada.

The formula by which equalization payments are made is based on averages across the country. Here, we’re talking about taxation rates and revenue-generation, based on the national averages of Canada. Provinces that fall below these averages are ‘have not’ provinces. Those who fall above it are ‘have’ provinces. The three wealthiest provinces are usually Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta. But all three of these provinces have fallen into ‘have not’ status at various points. In 2017-18, in order of amounts received, the have-nots are: Quebec, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Prince Edward Island. Quebec, it should be noted, will receive more than the other ‘have-nots’ combined. The ‘have’ provinces this year are Alberta, British Columbia, Newfoundland & Labrador, and Saskatchewan.

The equalization payments, though, are not a case of taking money from Alberta to pay for Quebec’s social programs. The funds are not based on how much one province pays for its health care system, or for a universal child care system, or cheap tuition at the province’s universities (Quebec has both universal child care and cheap tuition for in-province students). Rather, the funds come out of the same general revenue stream that Ottawa has to fund ALL of its programmes and services. And, each and every Canadian contributes to this revenue stream. Thus, the fine people of Westmount contribute more to equalization payments (and general revenue) than the middle-class residents of suburban Calgary, or a person in a lower income bracket in Saskatchewan. And, because there are more Quebecers than there are Albertans, Quebec actually contributes more to the equalization payment scheme.

It is not just angry Albertans who believe they are getting hosed by the federal government. Many Quebecers will rail against their province’s funding priorities and point to the province’s status as a ‘have not’ as to why it should not have these programmes. Both positions are factually wrong, and based on a fundamental misunderstanding of Canada’s equalization payments.

Mis-Remembering the Civil War

May 15, 2017 § Leave a comment

While it is easy to forget foreign wars, it is not so easy to forget wars fought on one’s own territory. Reminders are everywhere — those statues, those memorials, those museums, those weapons, those graveyards, those slogans. While one may not remember history, one cannot avoid its reminder. — Viet Than Nguyen.

Nguyen wrote this about Vietnam, and how reminders of the Vietnam War are all over the Vietnamese landscape. But this is true of any war-marked landscape, any territory haunted by war. It is true of the landscape I live in, the American South.

Driving to Chattanooga last week, I saw, but didn’t see, the half dozen or so Civil War memorials that dot the landscape off I-24. I saw, but didn’t see, the National Monument atop Lookout Mountain just outside of the city (from here, Union artillery bombarded Confederate-held Chattanooga). I am sure I’m not the only one who experiences this. We historians like to talk about memorials, about their power and all of that, but most memorials are simply part of the landscape, no longer worth remarking upon.

Most of the Civil War memorials were erected in the half century or so following the war, and thus, have had another century or so to blend into the background. My personal favourite of these memorials is one that lies within a chainlink face, on the side of a hill, above a hollow, hard up against the interstate.

The Civil War was obviously fought on Southern territory, as it was the Confederacy that tried to leave the Union. And it remains the most mis-remembered of all American conflagrations, of which there have been many. Americans in the North and the West think the Union went to war to end slavery. And many Americans in the South (by no means all, or, even a majority, I don’t think) think that the war was fought for some abstract ideal, like states’ rights. Both are wrong. The Confederacy seceded due to slavery, as the Southern states felt the ‘peculiar institution’ to be under attack by Northerners. But this is not why the North went to war in 1861; the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t come about until 1862, enacted on New Year’s Day 1863. Prior to that, the Union was fighting for, well, the union.

To return to the landscape of the South, with its battlefields, its many monuments, and to the parts of the landscape still physically scarred by the war, over 150 years ago, there is this constant reminder. This, I would like to humbly suggest, is why the Civil War has remained such a bugaboo for the South.

I oftentimes get the feeling that the larger country would like to just forget the Civil War ever happened, to move on from it. Maybe this is not true for all Americans, particularly African Americans (given slavery ended with the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865). But, it is certainly a trope I notice in my adopted country. But for the South, it couldn’t forget the war even if it wanted to.

Both the Union and Confederate armies marched up and down Tennessee, between Nashville and Chattanooga, along the railway that runs between the two cities. That railway runs next to I-24 for much of that stretch, at most a few miles apart. There are a series of battlefields between the two cities and, of course, the fall of Chattanooga in Autumn 1863 is what allowed the Union Army of General Sherman to march into Georgia and towards Atlanta.

It is hard to forget and move on from a war when there are reminders of it in almost every direction. And mis-remembering the Civil War also serves a purpose beyond the macro political. For one, it removes the nasty part of the rationale for the war on the part of the Confederate States: slavery (this also, obviously, has a macro-political impact). This allows some Southerners to mis-remember the Civil War in order to claim their ancestors who fought in it, to celebrate those that came before them for defending their homes, family, and so on.

Nevermind the inconvenience of slavery, or the fact that these very ancestors in the Confederate Army were deeply resentful of being the cannon fodder for the small minority of the Confederate States of America who actually owned slaves. Nevermind that these ancestors recognized they were the pawns in a disagreement between rich men. Nevermind the fact that these ancestors didn’t own slaves. In fact, that makes it easier to claim and sanitize these men. They were innocent of the great crime of the Confederacy.

And thus, it is easy to take this mis-remembered vision of one’s ancestors fighting in the Civil War for the Confederacy. It is easy to forget that war is terrifying, and to forget the fact that these ancestors, like any soldier today, spent most of their time in interminable boredom, and only a bit of time in abject terror in battle. It is easy to forget all of this, and thus, it is easy to mis-remember the essential reason why this war happened: slavery.

History & Memory and Abraham Lincoln

March 27, 2017 § 12 Comments

Lincoln’s birthday came and went in February, largely ignored in Tennessee and other Southern states. In the wake of his birthday, this image came floating through my Twitter feed. This is an interesting take on the question of history and memory of the Civil War. It fascinates me on both levels.

Factually, there is not much in this that is true. And the interpretation presented in this poster is, well, wrong. The part on top, with the spelling and grammatical mistakes, was tacked onto the Wanted poster by someone as it travelled through the right wing, Confederate social media world. I don’t know who did it.

Note how the unknown commentator claims that Lincoln waged an unholy war against the South. The Civil War, of course, was begun by the Confederacy, when it attacked Fort Sumter, in the harbour of Charleston, SC, on 11 April 1865. Thus, the war is not the fault of the Union. Fort Sumter was a fort held by the United States military, constructed in the wake of the War of 1812. There are no ‘hard facts’ that can be presented to deny this historical truth.

But, of course, fact and memory are not the same thing. And this is why the question of history and memory fascinates me. It’s not simply a matter of how we remember history as individuals, as our own individual memories are a function of society as well, but it’s also a question of how all of our individual memories work in concert with each other to form cultural memory.

Certainly, in the South, the Civil War is remembered differently from the North. And it is not always remembered in a cartoonish, neo-Confederate manner as this. On a more basic level, many Southerners can express distaste for the actual causes of the war and the war aims of the Confederacy and a deep pride in their ancestors’ gallantry in battle against the North. Hence the romance and popularity of Civil War re-enactors and their romance of the Confederacy. And, of course, there is a careful parsing of the larger context of the Confederacy and its reasons for fighting the war in the first place.

Slavery is the first or second thing mentioned in every single Confederate state’s articles of secession. It was central to the war aims of the Confederacy. It was not, however, central to the war aims of the Union, despite what many Northerners believe. It was not until the Emancipation Proclamation came into effect on 1 January 1863, nearly two years into the war, that the end of slavery became a Northern war aim. In short, then, the Civil War happened, from the perspective of the Confederacy, over slavery. Not states’ rights (had it been, the fight over the entry of new states to the Union and whether they’d be slave states or not, would not have happened).

And clearly, Lincoln is remembered differently on either side of the Mason-Dixon line. But there is also a question of history. When the Republican Party tweeted a fake quote from Lincoln for Lincoln’s Birthday (in a tweet that has since been deleted), it wasn’t the fake quote that amused me, it was the GOP’s statement. Lincoln certainly did not bring the nation together. His election was the excuse the Confederacy used to justify secession.

But at any rate, to return to the original issue here of the differing memories of the Civil War and un-reconstructed Southerners: One could indeed argue that Lincoln violated the Constitution. Many people have made this argument, including respected historians and constitutional scholars. Lincoln was very aware of his expansionist reading of the Constitution and reminded his opponents that they could question him, through the ballot box and via the court system. Ultimately, however, his expansion of the Constitution has been recognized by scholars as an historical fact, more or less.

But there is also the question of other means of bending the Constitution. In the case of habeus corpus, Art. I. Sec. 9, cl. 2 of the Constitution reads:

The Privilege of the Writ of Habeus Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public safety may require it.

However, Article I of the Constitution lays out the powers of Congress, not the Executive (that’s Article II). However, Congress can delegate authorities to the Executive, and has (for example, during World War I, the Food and Fuel Control Act of 1917). But, Congress had not delegated this power to Lincoln. Thus, in ex parte Merryman, a federal court decision in 1861, Justice Roger Taney, who was the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, but sitting as a federal court justice, found Lincoln’s suspension of habeus corpus and his delegating of this power to United States Army officers to be beyond the law, that the suspension of habeus corpus was limited to Congress, which could, of course, delegate this power. Merryman, however, was ignored by Lincoln on the grounds of necessity due to the unusual circumstances of the war. He argued that the Civil War was exactly situation noted in the Constitution, a case of rebellion. And, furthermore, he argued that the President has had to act many times when Congress was not in session. Indeed, this is true, dating back at least Jefferson’s era. In these cases, the President is expected to seek post facto permission for his actions from Congress. Indeed, in 1863, Congress passed An Act relating to Habeas Corpus, and regulating Judicial Proceedings in Certain Cases.

Indeed, in my copy of Richard Beeman’s Penguin Guide to the United States Constitution, which I assign every semester, as it annotates the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, Beeman merely states the following:

On at least a few occasions American presidents have suspended while either suppressing rebellion or protecting public safety.

Beeman then uses President Lincoln and the Civil War and President George W. Bush in the wake of 9/11 as examples. That’s all. In other words, this is a recognized power of the president, though Beeman does note that Bush based his actions on the USA Patriot Act, which is obviously an act of Congress.

As for the treason claimed in the Wanted post, I’m not sure where this comes from, given that the attempted secession by the Confederacy was, by definition, a treasonous act. Treason is an attempt to overthrow or betray one’s country. Certainly, the Confederates felt that the American government had overstepped its bounds and was attempting to claim the right to rebel, as the Founding Fathers had in the Declaration of Independence.

Nor did Lincoln imprison 40,000 Northerners in military prisons during the war. I’m not even certain where such a number would come from.

As for the question of the plight of Southerners under Union occupation, that is another thing entirely. Certainly, federal troops did commandeer supplies and property. They did rape Southern women. But, the argument about the loss of civil rights, well, the Confederacy did start the war. There was no official declaration of war, given that the Union refused to recognize the Confederacy, nonetheless, there was most certainly a war And the war was fought in Southern territories. Thus, the suspension of civil liberties in a territory of open rebellion should not be surprising.

Nonetheless, while I would not state that the vision of Abraham Lincoln in this Wanted poster is a common one in the South, there is a small fringe that does view him in this manner. And I also do not find this surprising, given the romanticization of the Civil War in the minds of many (and not just in the South). Lincoln was the enemy, obviously. And so it should not be surprising that someone, thinking it clever, created this Wanted poster (though I cannot speak to the editorialization attached to it).

In this romanticized version of the Civil War I have seen up close, at County Fairs and the like in Alabama and Tennessee, something interesting happens to the Civil War. Race is removed from it, in that the Sons of the Confederacy, the ones who dress up and Civil War garb and re-enact the war, insist they have no racial malice and that there is no racial malice behind their play-acting nor flying of the Confederate Battle Flag (whether or not this is true is a matter for another blog post). Rather, they claim, they are celebrating the gallantry of their ancestors against the Northern incursion (and, of course, the reasons for that incursion are elided).

And this brings me to what I see as the greatest irony of the lionizing of the Confederacy. I had a student who wrote an MA thesis on the Confederate soldiers between the Battle of Shiloh in southwestern Tennessee in April 1862 and the Battle of Mobile Bay in southern Alabama in August 1864. She used soldiers’ diaries as a major primary source. Shiloh was their first battle and many of these men responded much as you’d expect: abject terror at the actual grizzly face of mid-19th century war. And almost overnight, these young men went from being keen to be battle-tested to bitter. They were bitter at their inadequate supplies and medical care and leadership. But they were also bitter that they were being compelled to fight for the right of rich men to own slaves. As they marched South, chased by the Union Army through Mississippi and Alabama to Mobile Bay, they became increasingly angry and bitter. Those that survived did fight, against insane odds. And generally lost in this theatre of war, which was very different than the one commanded by Robert E. Lee in Virginia. In Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi, they were outgunned, outmanned, and victim to poor leadership. But even the soldiers in Lee’s Army of Virginia were well aware of the irony that they, too poor to own slaves, were laying their lives on the line for the rich slave owners.

It’s certainly a historical truism that poor men are the cannon fodder for the rich. Even today, the US Armed Forces tend to draw their recruits from the poorer areas of the South. So that the poor white men of the South found themselves in grey uniforms and fighting the US Army should not be surprising. So, in many ways, this is what these men, the Civil War Confederate re-enactors are interested in: the plight of poor men. And celebrating their ancestors. But, their ancestors were on the wrong side of history. And the wrong side of the Civil War.

And so they’re left with the uncomfortable problem of unsorting the simple fact of slavery and racism from their views of the Civil War. Hence the rise of the states’ rights claim. Or others. The simple fact is that they’re confronted with a double dose of difficult knowledge in confronting the Confederacy and the Civil War. First, the slavery issue. Second, their ancestors’ plight of fighting and dying for rich, slave-owning plantation owners. And perhaps this is their way out of the racial conundrum: these men and women, their ancestors weren’t the slave owners.

Left Wing Nut Jobs

February 20, 2017 § 8 Comments

We tend to live in ideological echo chambers these days. This is as true of the left as it is of the right and of the centre. But something has shifted in recent months that I find rather interesting. Until 2015, liberals and lefties could, and did, say with smug superiority that they dealt in facts and reality and too many people on the other did not (the latter is proved by the ‘alternative facts,’ or lies, that come out of Whitehall in London and the White House in DC, for example).

But since the autumn of 2016, I have been harangued on Twitter by leftists who trade in alternative facts and lies themselves. In October, I found myself in the cross-hairs of the anti-Hillary Clinton left. I had been having a discussion with one of my tweeps about President Bill Clinton’s attempts to introduce universal health care coverage in the United States in 1992-94. This push was led, to a large degree, by Hillary Clinton. It failed for a multitude of reasons, but the simple fact of the matter is that Mrs. Clinton and her husband attempted to introduce universal health care to the US.

During this discussion, I got attacked, in increasingly vicious language, by two leftists who apparently believed that Mrs. Clinton is the face of evil incarnate. They accused me of lying, and, of course, being a Clinton apologist, amongst other things. Not all that interested in this argument, I posted a link to the Wikipedia page explaining this (note that ‘Hillarycare’ also redirects to this page). Sure, it’s Wikipedia, but it gives a general idea of what happened. Not good enough for one of my accusers. She pointed out Wikipedia is ‘not a primary source.’ No, it’s not. But there is a whole bibliography leading to such sources. So, instead, she sent me links to heavily redacted documents and heavily edited YouTube videos of Mrs. Clinton’s speeches on the matter, including one video that showed her in four different outfits. None of this changes historical fact.

In December, it was British leftists who insisted that white people had been slaves in the United States. This isn’t really anything new, the Irish have been claiming they were brought here as ‘slaves,’ but now this was expanded to include the Scots, English, and Welsh. And they did not mean what people usually get confused, which is indentured servitude. They meant that white people were chattel slaves like Africans. In this case, though, they provided no sources, just their beliefs. And, as one pointed out to me, she was entitled to her opinion. Sure. She is. But she’s still wrong. And I have the realities of history behind me on that one.

And then, a couple of weeks ago, the subject was the Civil War in the US. The Republican Party tweeted a Happy Birthday to the first Republican President, Abraham Lincoln, claiming that Lincoln united the country. Whatever one thinks of Lincoln as president, and I consider him one of the best presidents all-time (and it’s not just me, as my new favourite Wikipedia page shows), he did not unite the country. Lincoln’s election was the excuse used for Southern secession. So, in the midst of a conversation with a tweep, also an historian on this matter, I got harangued by a lefty.

He insisted that slave owners ‘were killing in the name of slavery from 1856 on.’ He wasn’t wrong. And I could point to events such as Bleeding Kansas in 1854. But, that doesn’t change the simple historical fact that Secession began with Lincoln’s election.

In all three cases, my credentials as an historian were challenged. I have been called a ‘Professor of Bullshit,’ a ‘Doctor of Horseshit.’ I have been called a fascist, and a genocidal apologist (of what genocide, I’m not sure, I’m presuming she meant the genocide of white people sold as slaves in the 18th and 19th century). In all three cases, lefties have based ‘arguments’ on ‘alternative facts,’ or, what I would call bullshit. But all the weight of historical reality meant nothing to them. They didn’t like the facts, so they decided they weren’t true.

This is deeply disturbing.

Writing the History of the Trump Era

February 14, 2017 § 4 Comments

A couple of weeks ago, I was asked how future historians will be able to tell our history? We live in what is allegedly a post-fact era. First things first, whatever you want to call it, post-fact, post-truth, alternative facts, these are all just lies. I have already commented on this. Nonetheless, whether this is just a re-labelling of lying, we are still in this cultural moment. Every day the Trump administration deals in what White House Counsel KellyAnne Conway calls ‘alternative facts.’ What is the truth now, my interlocutor wanted to know?

I have been asked this question in a variety of ways in the past year and it is a real challenge we face. But we don’t face in terms of future historians, academics and journalists are already facing the problem. Michael A. Innes, a good friend of mine, has been thinking about this of late too. He notes that

Media outlets come in all shapes and sizes. Some are loud and boisterous, while others are more stoic. “Newspapers of record” are a recognized form of the latter. Some try to report what happened, while others try to convince readers why and how they happened. Media output, in other words, can serve more than one purpose, and only one of them is to provide researchers and analysts with a source of evidence needed to determine the factual basis of past events: what happened, when it happened, who was involved, what they said about what happened and so on. Reconstructing past events is a tricky business, and some media environments are so highly politicized – the rhetoric so overheated and contentious – that verifiable facts are almost impossible to discern from the collection of color and misdirection in which they’re embedded.

Indeed. The reconstruction of the past is indeed a tricky bit and I will go further than Innes and argue that it is an inherently political act. This is true whether it’s on the minor scale, such as I did in reconstructing a version of the history of Griffintown, Montreal (and yes, I am enjoying linking my own book). But it’s also what societies and cultures do anyway.

When we reconstruct the past, we do so from a variety of sources, including printed records, including government documents, diaries, published work, literature. We also use film, TV shows, documentaries, and music. We use oral sources, both those already collected and ones we collect. And we also make use of the digital: Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, blogs, etc. We have to make decisions in what gets included in our reconstructed histories.

Historians, we tend to go further than journalists. Innes notes that some media outlets report on what happened, whilst others focus on why and how they happened. And quite often the latter try to convince you of the version of events they are pushing. This is the difference between, say, The New York Times and Breitbart, or the CBC and FoxNews. The Times and the CBC deal in facts in reporting the news, and editorials are clearly labelled. In the case of Breitbart and FoxNews, there is a blurring of ‘news’ and editorials.

When I teach, I always remind my students that we are more interested in the how and the why of history, we need to move beyond facts and into interpretation. How do we do that? Logic and reasoning. We use other scholars as guides. We read what other historians have written on the subject, or an analogous subject. We consider their interpretations based on the evidence. We agree or disagree. Or we agree and see another possibility. And so on.

Back in Grade 2 or thereabouts, my teacher introduced us to the who, what, when, where, why and how? The key questions for all situations. So in writing history, we begin with the who, what, when, and where. We establish the facts. And we establish these from our sources. Even in this post-fact era, there are still facts. They still get reported, they’re still plain to find in doing research. And from there, we ascertain the why and the how.

So how do we source that in the post-truth world? Innes notes the guerrilla archiving of data, creating an archive of truth and records of the real world to counter the post-factual. But there are other, more simpler ways we do this through the ‘reading’ of our sources, whether they are government documents, newspapers, novels, films, music, Twitter, and so on. When we read these sources, we do so within a cultural context, of course. And we do tend to have strong bullshit detectors.

My MA thesis tells the story of the Corrigan Affair, which erupted in Sainte-Sylvestre, Quebec, in late 1855 when neighbourhood bully, an apostate, Robert Corrigan, was beaten to death by a gang of his Irish-Catholic neighbours at the county fair. When his murderers evaded capture for the next six months, all hell broke loose in a highly sectarian Canada. Anglo-Protestant politicians and newspapers were beside themselves over the fact that these Irish-Catholic ‘hooligans’ managed to evade the state’s attempts to bring them to justice. They did so through the help of their neighbours and an intimate knowledge of geography of the Appalachian foothills of southern Quebec.

The local Anglican priest in Saint-Sylvestre, Rev. William King, was ground zero for the ‘alternative facts’ of the Corrigan Affair. In daily dispatches to government ministers and the Quebec City press, Rev. King constructed an alternate reality where the Irish-Catholics of Sainte-Sylvestre were parading around openly armed and threatening Anglo-Protestant, beating them nearly to death for fun. He told of marauding gangs of Irish-Catholics breaking into homes in the middle of the night and tearing homes to pieces and beating the men and boys of the house. Rev. King’s invented reality was accepted verbatim by government ministers and the Quebec City press.

So how did I find out what happened in Saint-Sylvestre in the fall and winter of 1855-56? I reconstructed events through a mixture of sources, both government and official and vernacular. I relied on petitions from the Irish-Catholics of Saint-Sylvestre, who claimed to be brutalized by the Orange Order. I relied on the French Canadian press of Quebec, which watched both sides with bemusement. I read the depositions of the French Canadians of Saint-Sylvestre, who were similarly bemused by their neighbours’ actions. and from these varying sources, I reconstructed the events of the Corrigan Affair. I learned to tell fact from fiction, or at least something that looked more likely to have occurred than not.

And this is what historians will do when they tell the story of our time. They will look at the lies that are produced at the White House and then compare that to what other sources say about what is going on, including the media, but also our Twitter feeds, our Facebook posts, our Reddit commentary. Maybe even blogs like mine.

We will continue to examine history as we always have, sifting through varying and contradictory versions of events to reconstruct what actually did happen. And, of course, being a public historian first and foremost, I will be fascinated by the myth-making at the White House, and the puncturing of that myth by the rest of society, about the hows and whys we choose to remember this time.

Cranky White Men and Viola Desmond

December 14, 2016 § 4 Comments

Last week, the Canadian government announced a new face for the $10 bill. Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. MacDonald (1867-73; 1878-91), has long been featured on the $10, but Canada has sought to modernize our money and to introduce new faces to the $5 and $10 bills. A decision on the $5, which currently features our first French Canadian PM, Sir Wilfrid Laurier (1896-1911), will be made at a later date.

Viola Desmond will be the face of the $10 bill starting in 2018. Desmond is a central figure in Canadian history. On 8 November 1946, Desmond’s car broke down in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. Desmond was a cosemetician, trained in Montréal and New York, and operated her own beauty school in Halifax. And she was quite successful. So, stuck in New Glasgow over night, she went to see a movie to kill some time. She bought her ticket and took her seat. Desmond was near-sighted, so she sat in a floor seat. Problem is, she was black. And Nova Scotia was segregated; whites only on the floor, black people had the balcony. She was arrested. The next morning, she was tried and convicted of fraud. Not only were black people prohibited from sitting in the main bowl of the theatre, they also had to pay an extra cent tax on their tickets. Desmond had attempted to pay this tax, but apparently was refused by the theatre. So, she was fined $20 and made to pay $6 in court costs.

Desmond is often referred to as the ‘Canadian Rosa Parks,’ but truth be told, Rosa Parks is the American Viola Desmond. Unlike Parks, though, Desmond wasn’t a community organizer, she didn’t train for her moment of civil disobedience. But, Nova Scotia’s sizeable African Canadian community protested on her behalf. But, not surprisingly, they were ignored. She also left Nova Scotia, first moving to Montréal, where she enrolled in business college, before settling in New York, where she died on 7 February 1965 of a gastrointestinal hemorrhage at the age of 50.

I am on a listserv of a collection of Canadian academics and policy wonks. I have been for a long time, since the late 1990s. A discussion has broken out, not surprisingly, about Desmond being chosen as the new face of the $10. The government initially intended to put a woman on the bill. A collection of white, middle-aged men on this listserv are not pleased. They have erupted in typical white, middle-aged male rage.

One complains that the Trudeau government commits new outrages daily and he is upset that “they are going to remove John A. Macdonald from the ten dollar bill to replace him with some obscure woman from Nova Scotia whom hardly anyone has ever heard of.” He also charges that Trudeau’s government would never do this to Laurier (another Liberal), whereas Sir John A. was a Conservative. On that he’s dead wrong.

Another complains that:

Relative to John A., Viola Desmond is no doubt a morally superior human being. If we are to avoid generating our own version of Trumpism, we must be careful not to tear down symbols of our shared history by applying current, progressive criteria to determine who figures on the currency.

Imagine with what relish Trump would tear into his opponents if the US eliminated George Washington and Thomas Jefferson from their currency. Both were slave owners – presumably far worse crimes in present terms than John A’s alcoholism or casual attitude to bribery.

Seriously. All I can say to this is “Oh, brother.” But it gets worse. A third states that:

I have to agree with —–’s sentiment here. We have to stop doing nice, progressive things just because we can. There is a culture war, and we need to be careful about arming the other side.But I would say that having such things enacted by a government elected by a minority of Canadians doesn’t help. (Likely, the NDP and the Greens and even some Conservatives would have supported such a resolution, but) it does contribute to a sense of government acting illegitimately. It contributes to cynicism and outrage to have Trump as president-in-waiting with fewer votes than Clinton, for example.