On Experts & Anti-Intellectualism

July 5, 2016 § 5 Comments

Nancy Isenberg‘s new book, White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, is attracting a lot of attention. No doubt this is, in part, due to the catchy title. White trash is a derogatory and insulting term, usually applied to poor white people in the South, the descendants of the Scots-Irish who settled down here prior to the Civil War, the men who picked up their guns and fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. (Oddly, the term is not really applied all that often to poor white people in the North).

I am also deeply suspicious of books that promise to tell me the “untold” or “true” story of anything. And certainly, if you asked American historians if class was an “untold story”, they’d laugh you right out of their office. But no doubt the title is due to Viking’s marketing department, not Isenbeg.

Nonetheless, I bought the book, but as I was doing so, I read some of the reviews on Amazon.The negative ones caught my eye. Most of the negative reviews were either misogynistic or anti-Semitic. But, one, by someone calling themselves Ralphe Wiggins, caught my eye:

This book purports to be a history of white trash in America. It is not. It is a series of recounting of what others have said about the lower white classes over the past 400 years. In most cases the author’s summarizations are a simple assertions of her opinion.

…

The book is 55% text, 35% references and 10% index. The “Epilog” is a mishmash of generalizations of Isenberg’s earlier generalizations.

Let us now parse Wiggins’ commentary. First, Wiggins complains that Isenberg simply summarizes “her opinion” and then generalizes her generalizations. Clearly, Wiggins does not understand how historians go about their craft. Sure, we have opinions and politics. But we are also meticulous researchers, and skilled in the art of critical thinking. The argument Isenberg makes in White Trash are not simply her “opinion,” they’re based on years of research and critical thinking.

Second, Wiggins complains that the book is 35% references and 10% index. Of course it is, it’s an academic work. The arguments Isenberg makes are based on her readings of primary and secondary sources, which are then noted in her references so the interested reader can go read these sources themselves to see what they make of them. Revealing our sources is also part of the openness of scholarship.

Wiggins’ review reminds me of Reza Aslan’s famous turn on FoxNews, where he was accused by the host of not being able to write a history of Jesus because he’s a Muslim. Aslan patiently explained to her over and over again that he was a trained academic, and had spent twenty years researching and pondering the life and times of Jesus. That was what made him qualified to write Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth.

But all of this, Wiggins’ review, Aslan’s turn on FoxNews is symptomatic of a bigger problem: the turning away from expertise. In the wake of the Brexit vote, the satirical news site “News Thump” announced that all experts would be replaced by Simon Kettering, a local at the neighbourhood pub:

Williams knows absolutely everything about any subject and is unafraid to hold forth against the received wisdom of 400 years of the scientific method, especially after four pints of Strongbow.

Amongst his many accomplishments Simon is remarkably well-informed about optimal football formations, the effects of political events on international capital and bond markets, and the best way to pleasure a woman – possibly his favourite subject.

His breadth of knowledge is all the more impressive as he doesn’t even need to bother spending ten seconds fact-checking on Google before issuing a firm statement.

As my good friend, Michael Innes, noted in response:

Yep. Personally, I’m looking forward to all the medical and public health experts at my local surgery being fired and replaced with Simon. Not to mention the car mechanics at my local garage. I’m sure with a little creative thinking (no research!!!) we can dig deeper and weed out yet more of the rot, too.

See, experts can be useful now and then. And Nancy Isenberg is certainly one, given that she is T. Harry Williams Professor of History at Louisiana State University.

Stupid Memes, Lies, and Ahistoricism

June 27, 2016 § 4 Comments

There is a meme going around the interwebs in the wake of last Thursday’s Brexit referendum and decision. This meme is American and has appeared on the FB and Twitter feeds of pretty much every conservative I know. And, like nearly all memes, it is stupid. And ahistorical.

I watched an argument unfold on a friend’s FB wall over the weekend, where one of the discussants, in response of someone trying to historicize and contextualize the EU, said that “History is irrelevant.” He also noted that history is just used to scare people. OK, then.

But this is where history does matter. The European Union is a lot of things, but it is not “a political union run by unaccountable rulers in a foreign land.” Rather, the EU is a democracy. All the member states joined willingly. There is a European Parliament in Brussels to which member states elect members directly. Leadership of the EU rotates around the member states.

And, the 13 Colonies, which rose up against the British Empire in 1774, leading to the creation of the United States following the War of Independence, were just that: colonies. The United Kingdom is not and was not a colony of Europe.

The two situations are not analogous. At all. In other words, this is just another stupid meme. #FAIL

The Sartorial Fail of the Modern Football Coach

January 13, 2016 § 2 Comments

As you may have heard, the University of Alabama Crimson Tide won the college football championship Monday night, defeating Clemson 45-40. This has led to all kinds of discussion down here in ‘Bama about whether or not Coach Nick Saban is the greatest coach of all time. See, the greatest coach of all time, at least in Alabama, is Paul “Bear” Bryant, the legendary ‘Bama coach from 1957 until 1982.

Bear won 6 national titles (though, it is worth noting the claim of Alabama to some of these titles is tenuous, to say the least). Saban has now won 5 (only 4 at Alabama, he won in 2003 at LSU). I don’t particularly give a flying football about this argument, frankly. But as I was watching the game on Monday night, everytime I saw Nick Saban, I just felt sad.

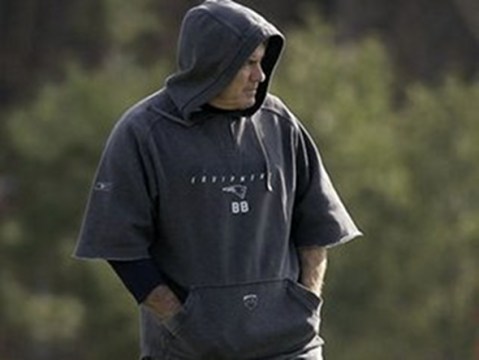

Nick Saban is a reasonably well-dressed football coach, so there is that. But, he looks like he should be playing golf. Poorly-fitting pants and and a team-issued windbreaker. He could be worse, he could be Bill Bellichk of the New England Patriots, who tends to look homeless on the sidelines.

Nick Saban is a reasonably well-dressed football coach, so there is that. But, he looks like he should be playing golf. Poorly-fitting pants and and a team-issued windbreaker. He could be worse, he could be Bill Bellichk of the New England Patriots, who tends to look homeless on the sidelines. But that’s not saying much, is it?

But that’s not saying much, is it?

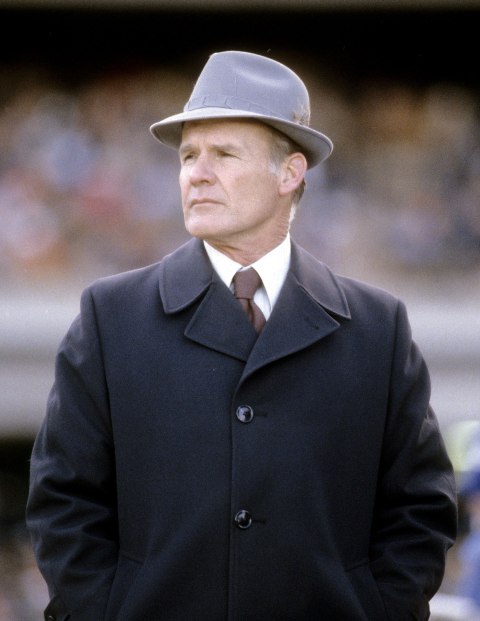

Saban and Bellichick are a far cry from Bear Bryant and Tom Landry, the legendary Dallas Cowboys coach. Bryant and Landry both wore suits on the side lines. Bryant did have an unfortunate taste for houndstooth, of course. But Landry stood tall in his suit and fedora.

There’s something to be said for looking sharp on the sidelines. I miss these well-dressed coaches.

Place and Mobility

January 8, 2016 § 7 Comments

I’m reading a bit about theories of place right now. And I’m struck by geographers who bemoan the mobility of the world we live, as it degrades place in their eyes. It makes our connections to place inauthentic and not real. We spend all this time in what they call un-places: airports, highways, trains, cars, waiting rooms. And we move around, we travel, we relocate. All of this, they say, is degrading the idea of place, which is a location we are attached to and inhabit in an authentic manner.

I see where these kinds of geographers come from. I have spent a fair amount of my adult life in un-places. I have moved around a lot. In my adult life, I have lived in Vancouver, Ottawa, Vancouver again, Ottawa again, Montreal, Western Massachusetts, Boston, and now, Alabama. If I were to count the number of flats I have called home, I would probably get dizzy.

And yet, I have a strong connection to place. I am writing this in my living room, which is the room I occupy the most (at least whilst awake and conscious) in my home. It is my favourite room and it is carefully curated to make it a comfortable, inviting place for me. It is indeed a place. And yet, I have only lived here for six months. In fact, today is six months sine I moved into this house. I have a similar connection to the small college town I live in. And the same goes for my university campus.

So am I different than the people these geographers imagine flitting about the world in all these un-places, experiencing inauthentic connections to their locales? Am I fooled into an inauthentic connection to my places? I don’t think so. And I think I am like most people. Place can be a transferrable idea, it can be mobile. Our place is not necessarily sterile. It seems to me that a lot of these geographers are also overlooking the things that make a place a place: our belongings, our personal relationships to those who surround us, or own selves and our orientation to the world.

Sure, place is mobile in our world, but that does not mean that place is becoming irrelevant as these geographers seem to be saying. Rather, it means that place is mobile. Place is by nature a mutable space. Someone else called this house home before me. This house has been here since 1948. But that doesn’t mean that this is any less a place to me.

The Ethno-Centrism of Psychology

December 30, 2015 § 6 Comments

I’m reading Jared Diamond’s most recent book, The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies?. Diamond, of course, is best known for his 1999 magnum opus, Guns, Germs & Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, a magnificent study of what led the Western world to dominance in the past several centuries. Diamond also kick-started the cottage industry of studies in World History that sought to explain how it was that the World came to dominate, and, in most cases, predicting the West’s eventual downfall. Some of these were useful reads, such as Ian Morris’ Why The West Rules For Now, and others were, well, not, such as Niall Ferguson’s Civilization: The West and the Rest.

At any rate, in his Prologue, Diamond talks about, amongst other things, psychology. He reports that 96% of psychology articles in major peer-reviewed, academic journals in 2008 were from Western nations: Canada, the US, the countries of Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Israel. Of those, 68% dealt with Americans. But it gets better, the vast majority of those were articles based on research where participants were undergraduates in psychology courses.

This is somewhat disconcerting as it means that the vast majority of what we know about human psychology from the academy is based on an ethno-centric, largely Americanized point-of-view. But, perhaps more damning, the majority of this opus is based on 18-22 year olds at universities across the US. That means these participants are predominately wealthy (relatively), American, and young.

Interestingly, we also know enough about the human brain and psychology to know that they evolve as we age. It is also clear from fields as diverse as history, psychology, anthropology, sociology, etc., that people are not all the same across cultures. In other words, applying what we may know about one issue, based on research on American undergraduates in psychology classes, has absolutely no bearing on elderly German men and women. Or, for that matter, middle-aged Chinese women.

Partisanship and American Politics and History

October 28, 2015 § 4 Comments

I am reading Andrew Schocket’s fascinating new book, Fighting Over the Founders: How We Remember the American Revolution, for a directed reading I’m doing with a student on Public History. I’m only about 45 pages into the book, but so far, it is very compelling reading, and also re-confirms my decision to walk away from a planned research project into the far right of American politics and its view of the country’s history.

Schocket argues that since the 1970s, Americans and American life and culture have become more partisan. He points to the internet, the dissolution of the Big Three networks’ monopoly on the news, self-contained internet communities, and the rise of ideological political spending outside of the two main parties (i.e.: the result of SCOTUS’ incredibly wrong-headed Citizens United decision). He also notes gerrymandering, and the evidence that suggests Americans are moving into ideologically similar communities.

I have never really bought this argument. This country’s entire political history has been based on political partisanship. Sure, the Big Three networks have lost their monopoly, but the bigger issue is the end of the FCC’s insistence on equal time for opposing viewpoints on the news. But even then, newspapers were little more than political organs in the 19th century. Self-contained communities in both the real world and the internet really only replace 19th and 20th century workplaces where people were likely to think similarly in terms of politics. True, Citizens United is a new wrinkle, but it doesn’t really change much in terms of partisanship.

We are talking about a country where the initial founding was controversial, as evidenced by the 20% of the population who were Loyalists during the Revolution. Then, during the first Adams administration, the Alien & Sedition Acts were passed for entirely partisan reasons. I’m not sure you can find an example in US history of a more partisan moment than one where those in power attempted to outlaw the political discourse of their rivals. This country also nearly came apart in the 1860s over what was, in part, a partisan divide between Democrats and Republicans. Republicans didn’t get elected in the South in the ante-bellum era. The South did not vote for Lincoln. Many Northern Democrats, the so-called copperheads, had Southern sympathies. Or there’s the tension between Democrats and Republicans in the early 20th century over the power of corporations. Or how about the battle over America’s place in the world after World War I? What about the McCarthyite era?

In short, while we live in an era of intense partisanship, this is nothing new for the United States. Partisanship is, in many ways, as American as baseball, apple pie, and Budweiser.

“War is Hell”: Public History?

September 16, 2015 § 2 Comments

This is Wesleyan Hall on the campus of the University of North Alabama. It is the oldest building on campus, dating back to 1855. Florence, the town in which the university is located, was over-run by both Union and Confederate troops during the Civil War. Parts of northern Alabama were actually pro-Union during the war and at least one town held a vote on seceding from the Confederate States of America. This was made all the more complicated by the fact that the CSA was actually created in Montgomery, Alabama’s capital, and the first capital of the CSA, before it moved to Richmond, Virginia.

Wesleyan allegedly is still marked by the war, with burn marks in the basement from when Confederate troops attempted to burn it down in 1864. A local told me this weekend that there is allegedly a tunnel out of the basement of Wesleyan that used to run down to the Tennessee River some 2 miles away.

The most famous occupant of Wesleyan Hall during the war was William Tecumseh Sherman. It is in this building that he is alleged to have said that “war is hell” for the first time. Of course, there are 18 other places where he is alleged to have said this. And herein lies the position of the public historian.

Personally, I think Sherman said “war is hell” multiple times over the course of the Civil War, and why wouldn’t he? From what I know of war, from literature, history, and friends who have seen action, war is indeed hell. But I am less interested in where he coined the phrase than I am in the multiple locales he may or may not have done so. What matters to me is not the veracity of the claim, but the reasons for the claim.

So why would people in at least 19 different locations claim that Sherman coined the phrase at that location? This, to me, seems pretty clear. It’s a means of connecting a location to a famous event, to a famous man, to raise a relatively obscure location (like, say, Florence, Alabama) to a larger scale, onto a larger stage. It ties the University of North Alabama to the Civil War. But more than that, since we already know the then LaGrange College was affected by the war, but the attempt to claim Sherman’s most famous utterance creates both fame for the university, and makes the claim that something significant connected to the war occurred on the campus. There are no major battlefields in the immediate vicinity of northern Alabama, so, failing that, we can claim Sherman declared that ‘war is hell’ in Wesleyan Hall.

Search Terms

August 28, 2015 § 3 Comments

Occasionally I look at the search terms that bring people to my blog. I did so yesterday. Amongst the usual searches that have to do with Ireland, Irish history, Montreal, Griffintown, etc., come two brilliant search terms: “somewhere a village idiot is missing its idiot” and “Stephen Harper inferiority complex.” I can’t help but think that those two searches were related.