Montréal: En construction

July 25, 2017 § 2 Comments

The running joke in Montreal is that a traffic cone should be our municipal symbol. From May to November or so annually, the streets of the metropole are a sea of traffic cones as workers frantically try to patch up roads thrashed by winter, and occasionally build something new. And annually, Montrealers kvetch about construction. As if it didn’t happen last summer and won’t happen next summer.

I was home last week, and it was the usual. Actually it’s beyond the usual. The city is awash in the orange beacons. Roads are dug up everywhere. But, something else occurred to me. This is not the status quo, this is not business as usual for my city. Instead, this is something new. This year, 2017, marks the 375th anniversary of the founding of the city in 1642. It is also Canada’s 150th anniversary since Confederation in 1867. This means that Montreal is seeing an infrastructural (re-)construction not seen since the late 1960s, in conjunction with Expo ’67, on Canada’s 100th anniversary. That boon saw the highway complex around the city built, as well as the Pont Champlain. Montreal also got its wonderful métro system out of that. But this infrastructural boom coincided with deindustrialization and the decline of the urban core of the city. Thus, what looked beautiful and shiny in 1967 had, by 2007, become decrepit and dodgy. There was no money for proper upkeep, so things were patched together.

Take, for example, the Turcot Interchange in the west end of the city. Chunks of concrete fell off it regularly, so there were these rather dodgy looking repair patches all over it. The Pont Champlain had outlived its expected lifespan of about 50 years. And the métro. Wow. While the trains still ran on time, more or less, and regularly, they were ancient.

The old Turcot Exchange. The different colourations of the concrete indicates patch work concrete, except, of course, for the rust and discolourations from water/ice.

But now, all this money is being showered on the city. The Turcot is being taken down and replaced with a level interchange. Work is on-going 24/7 on this. The old McGill University Health Centre (MUHC), which had been jerry rigged in a collection of century old buildings on avenue des Pins on the side of Mont-Royal, has a beautiful new campus on the location of the old Glen Rail Yards in NDG. The Pont Champlain is being replaced. Meanwhile, on the ride downtown on the Autoroute Bonaventure, on the A20 from the airport, one will find access to the downtown core blocked. The Bonaventure, a raised highway that bisects Griffintown (buy my book!) is being knocked down to be replaced with an urban boulevard. And while I am not entirely clear what the plans are for the Autoroute Ville-Marie under the downtown core, construction continues apace there. Meanwhile, the Société de transport de Montréal has new cars on the métro! At least on the Orange line. And, while they don’t actually feel air conditioned, they do have an effective air circulation system that, if you’ve ever experienced Montreal in the summer, you will appreciate.

Montreal’s new métro cars

So, for once, Montreal is not just being patched up. It is being rebuilt. For once, the powers-that-be have planned for the future of the city. And one day, who knows when, the city will be radically rebuilt and will have perhaps the most modern infrastructure in Canada, if not North America.

Go figure. No longer is my city a dilapidated, crumbling metropolis.

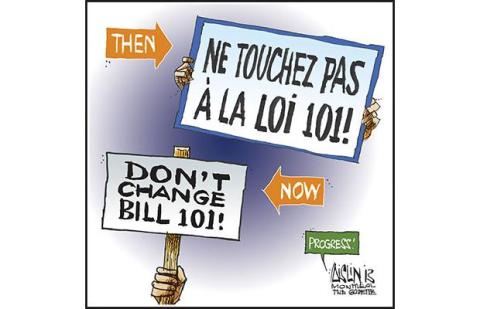

Bonne fête à la charte de la langue française!

May 31, 2017 § 1 Comment

Bill 101 is 40 years old this year. For those of you who don’t know, Bill 101 (or Loi 101, en français) is the Quebec language charter. It is officially known as La charte de la langue française (or French-Language Charter). It essentially establishes French as the lingua franca of Quebec. For the most part, the Bill was aimed at Montreal, the metropolis of Quebec. Just a bit under half of Quebec lives in Montreal and its surrounding areas, and this has been the case for much of Quebec’s modern history. Montreal is also where the Anglo population of Quebec has become concentrated.

When Bill 101 was passed by the Parti québécois government of René Levésque in 1977, there was a mass panic on the part of Anglophones, and they streamed out of Montreal and Quebec, primarily going up the 401 highway to Toronto. My family was part of this. But we ultimately carried on further, to the West Coast, ultimately settling in Vancouver. At one point in the 1980s, apparently Toronto was more like Anglo Montreal than Montreal.

Meanwhile, back in the metropole, nasty linguistic battles dominated the late 1980s. This included actual violence on the streets. But there were also a series of court decisions, many of which struck down key sections of Bill 101. This, in turn, emboldened a bunch of bigots within the larger Anglo community, who complained of everything, from claiming Quebec wasn’t a democracy to, amongst some of the more whacked out ones, that the Anglos were the victim of ethnocide (I wish I was kidding).

But, in the 30 years since, much has changed in Montreal. The city settled into an equilibrium. And I would posit that was due to the economy. Montreal experienced a generation-long economic downturn from the 1970s to the 1990s. In the mid-90s, after the Second Referendum on Quebec sovereignty failed in 1995 (the first was in 1980), the economy picked up. New construction popped up everywhere around the city centre, cranes came to dominate the skyline. And then it seeped out into the neighbourhoods. By the late 90s/early 2000s, Montreal was the fastest growing city in Canada. It has since long since slowed down, and Montreal had a lot of ground to catch up on, in relation to Canada’s other two major cities, Toronto and Vancouver. But the economic recovery did a lot to stifle not just separatism, but also the more radical Anglo response.

2013 editorial cartoon from the Montreal Gazette.

Last week, the Montreal Gazette published an editorial on the 40th anniversary of Bill 101. It was a shocker, as the newspaper was central to the more paranoid Anglo point-of-view, even as late as the mid-2000s. But, perhaps I should not have been surprised, as it was written by eminent Montreal lawyer, Julius Grey. He is one of the rare Montrealers respected on all sides. At any rate, Grey (who was also the lawyer in some of the cases that led to sections of Bill 101 being invalidated), celebrates the success of the Charte de la langue française. It has, argues Grey correctly, led to a situation where, in Montreal, both French and English are thriving. He also notes that there is much more integration now in Montreal than was the case in the 1970s, from intermarriage to social interaction, and economic equality between French and English. Moreover, immigrants have by-and-large learned French and integrated, to a greater or lesser degree, into francophone culture. Many immigrants have also learned English.

But the interesting part of Grey’s argument is this:

On the English side, dubious assertions of discrimination abound. It is important for all citizens to be treated equally, but often the problem lies in the mastering of French. The English minority has become far more bilingual than before, but many overestimate their proficiency in French, and particularly when it comes to grammar and written French. By contrast, francophones tend to underestimate their English.

In other words, speaking French is an essential to life in Montreal. And Anglos, I think, are more prone to over-estimating their French-language skills for the simple fact that it’s common knowledge one needs to speak the language.

Grey goes onto make an excellent suggestion:

These difficulties could be eased by the creation of a new school system, accessible to all Quebecers, functioning two-thirds in French and one-third in English. Some English and French schools would exist for those who do not wish to or cannot study in both languages, although most parents would probably prefer the bilingual schools.

However, this would never fly. The one-third English does not bely the demographics of the city (let alone the province, and I really don’t see the point of learning English in Trois-Pistoles). The urban area of Montreal is around 4 million (the population of Quebec as a whole is around 8.2 million). There are a shade under 600,000 Anglos in the Montreal region, largely centred in the West Island and southern and western off-island suburbs. That means Anglos are around 15% of the population of Montreal. The idea that Montreal is bilingual is given lie by these numbers.

Nonetheless, there is merit to this argument of an English-language curriculum in Quebec’s public schools (including in Trois-Pistoles). Like it or not, English is the lingua franca of the wider world, and global commerce tends to be conducted in that language. There is also the fact of the wide and vast English-language culture that exists around the globe. One of the things I enjoy about my own partial literacy in French (one that has certainly been damaged by not living in Montreal anymore) is the access to francophone culture, not just from Montreal and Quebec, but the wider francopohonie).

For any group of people or individual, there is a lot to be learned from bilingualism (or, multi-linguality). In Montreal (and Quebec as a whole), it could ensure that the city’s economic recovery in the past two decades continues. Along with this economic recovery has been a cultural renaissance in the city, in terms of music, film, literature, and visual arts. It is a wonderful thing to see Montreal’s recovery. And I want it to continue.

Update: Commemorating the Victims of the Irish Famine in Montreal.

May 29, 2017 § Leave a comment

Last week, the news out of Montreal was that the piece of land the Irish Memorial Foundation sought to create a proper memorial of the mass grave of Irish Famine victims had been sold to Hydro-Québec, which sought to build a power sub-station there, ironically to serve the burgeoning redevelopment of Griffintown.

But all is well that ends well, apparently. On Friday, Hydro-Québec and the Ville de Montréal issued a joint press release saying that they, along with Montreal’s Irish community, had come to an arrangement to see the redevelopment of a memorial to the 6,000 victims in that grave under what is now Bridge St.

And, frankly, it is about time that this project got underway.

Literature as History

February 16, 2017 § Leave a comment

I am reading Matthew Beaumont’s Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London. This nocturnal history of London was constructed through literature. He relies on everything from Geoffrey Chaucer to Charles Dickens to William Shakespeare, amongst others to reconstruct the nocturnal London, though he focuses particularly on the 16th and 17th centuries. The Amazon reviews are about what you would expect, especially the negative ones. They castigate Beaumont for writing ‘history’ using ‘literature.’ And you can see the logic here. Literature isn’t history, it’s make-believe. It’s fiction. And I can certainly hear some of my professors saying the exact same thing.

I am reading Matthew Beaumont’s Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London. This nocturnal history of London was constructed through literature. He relies on everything from Geoffrey Chaucer to Charles Dickens to William Shakespeare, amongst others to reconstruct the nocturnal London, though he focuses particularly on the 16th and 17th centuries. The Amazon reviews are about what you would expect, especially the negative ones. They castigate Beaumont for writing ‘history’ using ‘literature.’ And you can see the logic here. Literature isn’t history, it’s make-believe. It’s fiction. And I can certainly hear some of my professors saying the exact same thing.

I use fiction a fair lot when teaching. I assign ‘history’ for my students to read besides the textbook, but I also make wide use of fiction. This is true both in the case of literature and film. So how is literature history, you ask?

Literature is a reflection of the time in which it is written. This is true of historical fiction and non-historical fiction. The historical fiction of our era is a reflection of our attempt to find a way through changing and complex times. It is a reaching back for something simpler (as we imagine the past to be), or for an explanation of the world through the past. Literature, like film, reflects the mood of the times, the neuroses we, as a society, carry. What fascinates, puzzles, and frustrates us. It is, in many ways it is the id to our rational ego.

So Beaumont reconstructs a history of London through fiction, and in so doing, he discovers what London’s nighttime meant to writers in their time and their place in London’s past. Chaucer’s 14th century London is a very different beast from Shakespeare’s 16th and 17th century version, just as his is different from Charles Dickens’ 19th century London, which is different from Zadie Smith’s 20th and 21st century London. But each of those authors reflect the city as it was in those times and those places.

And while their stories may be fictitious, the city they are set in is not. Each of these authors takes great effort to reflect London, the London they knew, to their reader. And this is the point of using literature as an historical text. Fictitious as the stories may be, their settings are not.

And so Beaumont’s nocturnal journey through London after dark is, in fact, a history.

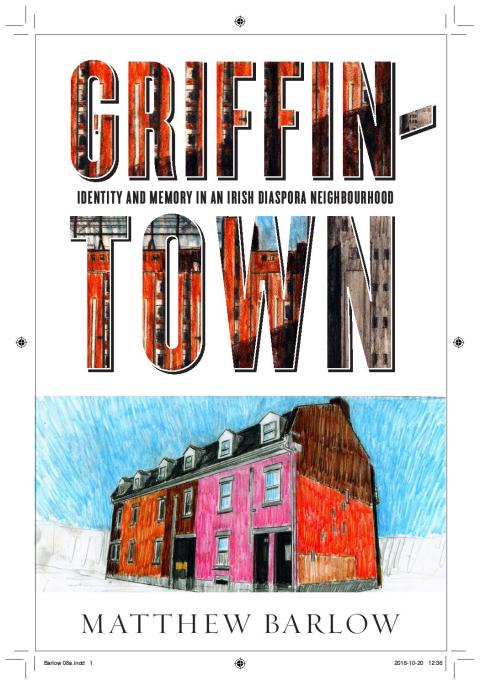

Griffintown

October 31, 2016 § 2 Comments

I just recently received the cover art for my forthcoming book, Griffintown: Identity & Memory in an Irish Diaspora Neighbourhood. It will be published in May 2017 by the University of British Columbia Press. To say I’m stoked is a minor understatement. The art work is by my good friend and co-conspirator on many things Griff, G. Scott MacLeod.

Gentrification: Plus ça change

September 14, 2016 § 2 Comments

I’m reading a book that is, for the lack of a better term, a biography of the Kremlin. I am at the part where the Kremlin, and Moscow itself, gets rebuilt after Napoléon’s attempt at conquering Russia. Moscow had been, until it was torched during the French occupation, a haphazard city; visitors complained it was Medieval and dirty. And it smelled. And not just visitors from Paris and Florence, but from St. Petersburg, too.

In the aftermath, Moscow was rebuilt along Western European lines, in a rational manner. And the city gentrified, the Kremlin especially:

This was definitely a landscape that belonged to the rich and the educated, to noblemen and ladies of the better sort. It is through the artists’ eyes that we glimpse the well-dressed crowds: the gentlemen with their top hats and shiny canes, the ladies in their bonnets, gloves, and crinolines. They could be leading citizens of any European state, and there is little sense of Russia (let alone romantic Muscovy) in their world.

Leaving aside the fact that there were no citizens of any European state in 1814, this sounds remarkably familiar. This is the same critique I have written many times about Griffintown and Montreal: as Montreal gentrifies, it is becoming much like any other major North American city.

But it is also true of gentrification in general. There is a part on the North Shore of Chattanooga, Tennessee, I really like. It finally dawned on me that it is because it reminds of me Vancouver architecturally, culturally, aesthetically, and in the ways in which the water (in this case the Tennessee River, not False Creek) is used by the redevelopment of this historically downtrodden neighbourhood. But. I could also be dropped into pretty much any North American city and see similarities: Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, New York, Boston, Seattle, Portland (Oregon), Cincinnati, Cleveland, Buffalo, Chicago, Atlanta, Nashville. These are all cities (amongst others) where I have seen the same tendencies.

And, obviously, one aspect of gentrification is the cleansing of the city of danger and vice. Just like Moscow was cleaned up in the aftermath of 1812.

The Death and Life of Griffintown

July 26, 2016 § 2 Comments

I was back in Montreal a couple of weeks ago to finish up shooting for the documentary my good friend, G. Scott MacLeod, and I have been working on for the past few years. We travelled around Griffintown, doing some B shots, and re-doing some other shots. And then we found ourselves at Parc Faubourg Sainte-Anne, on the site of the former St. Ann’s Church at the corner of de la Montagne and Basin. Across the street is one of the last remaining stands of 19th century rowhouses in Griff. And right behind and beside it is yet another condo development (because there never can be enough, right?).

Part of these rowhouses were part of a co-op. One Friday afternoon in April, a bunch of men in suits and hardhats showed up, milled around, pointed at things, and then disappeared. Later that night, the residents of the co-op were forced out of their homes. Their homes were quickly condemned and they weren’t even allowed to go back in to get their personal belongings (the fire department had to go back in to get the ashes of one woman’s husband). Why did this happen? Well, it seems that a water line had been opened and that had compromised the foundation of the 1867 building.

(photo courtesy of G. Scott MacLeod).

That Sunday night, around 10.30pm, a huge backhoe showed up and tore down the end unit of the co-op, the one with the leaky foundation. The residents were “temporarily” re-housed.

Today, the co-op units are empty, only three of them still stand. And they all have a notice of eviction on their front doors.

As we were filming, we were approached by a Griffintown old-timer. He doesn’t want his name used, so he will go unnamed. He showed us a bunch of photos on his cellphone of the suits and the backhoe. And he told us what he saw happen. He said that a retaining wall had been built behind the co-op units when excavation work began on the condos around it. But, interestingly, the wall behind the fourth unit of the co-op had somehow disappeared the week before the water leak. And, just as amazingly, it suddenly re-appeared after the fourth unit was torn down. As to who turned on the water, well, he left that to our imagination.

Whether or not his version of events is true or not, to me, this is symptomatic of the new Griffintown, one that is beholden to condo developers and the accumulation of tax money for the Ville de Montréal. We all know Montreal is a historically corrupt city, and the recent Charbonneau Commission detailed corruption in the Montreal construction industry.

And whether or not something fishy happened with respect to the co-op or not, the events of April do not pass the smell test. That no one seems to care is even more worrisome. Montreal is a wonderfully progressive city in so many ways, but Griffintown is a fine example of what happens when greed takes over. The city had this wonderful opportunity to remake an entire inner-city neighbourhood. And rather than engage in sustainable development, or even, for that matter, a liveable area, the Ville de Montréal took the money and ran. And this is to the city’s detriment.

Oh, and the residents of this co-op? Call me cynical, but I’ll be shocked if they end up back in their co-op. See, the developer’s office is right next door to the co-op and my guess is that these buildings will either also mysteriously fall down or become condos as part of this larger development.

Research Note: The Pont Champlain

June 4, 2014 § Leave a comment

Nearly every time I drive over the Pont Champlain, I turn my brain off, and don’t think about the crumbling infrastructure of the bridge, I don’t think about how far it is down to the St. Lawrence. I don’t think about how deep the river is. I don’t think about the litres of ink spilled in the Montreal newspapers, in both official languages, about the bridge. I don’t think about the fact that god-knows-how-many billion dollars are being spent to fix a bridge that needs replacing whilst the politicians in Ottawa and Quebec City continue to argue about how best to replace the bridge. I don’t really think the bridge is going to fall down, of course. But.

Nearly every time I drive over the Pont Champlain, I turn my brain off, and don’t think about the crumbling infrastructure of the bridge, I don’t think about how far it is down to the St. Lawrence. I don’t think about how deep the river is. I don’t think about the litres of ink spilled in the Montreal newspapers, in both official languages, about the bridge. I don’t think about the fact that god-knows-how-many billion dollars are being spent to fix a bridge that needs replacing whilst the politicians in Ottawa and Quebec City continue to argue about how best to replace the bridge. I don’t really think the bridge is going to fall down, of course. But.

So it was a nice change of pace to be finishing off a chapter of The House of the Irish on the dissolution of Griffntown in the 1960s, and to come across documents I’ve collected from the Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa, as well as newspaper articles from The Star, The Gazette and La Presse from the late 1950s and early 1960s, when the Pont Champlain was first opened, and it was a marvel of engineering, and then the city and federal government built the Autoroute Bonaventure into the city in preparation for Expo ’67.

The optimism! The excitement about a new bridge connecting Montreal to the South Shore! The excitement about the Bonaventure, which “sweeps majestically into the city, the river on one side, the skyline in front,” to quote one article from The Star. Next time I cross the Champlain, I’ll try to think of that.

Griffintown and the Importance of Urban Planning

May 12, 2014 § 6 Comments

This will be the first of a series of posts on Griffintown this week. I was in Montréal last week, mostly to finish up a bit of research on the Griffintown book, which, at least has a title, ‘The House of the Irish’: History & Memory in Griffintown, Montreal, 1900-2013. The last chapter of the manuscript deals with what I call the post-memory of Griffintown, the period of the past half-decade or so of redevelopment and gentrification of the neighbourhood. Griffintown was in desperate need of redevelopment, so let’s get that out of the way first and foremost. A large swath of near-vacant city blocks next to the Old Port, along the North Bank of the Lachine Canal, and down the hill from downtown, it was inevitable that it would attract attention.

My problem was never with redevelopment per se, then. My problem was with unsustainable development, willful neglect of the environment, of the landscape of the neighbourhood, and with blatant cash grabs by condo developers, and tax grabs on the part of the Ville de Montréal. And so that’s what we now have in Griffintown, for the most part.

In between conducting oral history interviews with my former allies in the fight for sustainable redevelopment, I wandered around Griffintown, Pointe-Saint-Charles, and Saint-Henri a fair bit. This was both professional interest and because I lived in the Pointe and Saint-Henri. I also had an interesting discussion with a clerk at Paragraphe Books on McGill College. Then there were the interviews.

My friend Scott MacLeod says that many of the condos going up in Griffintown look like “Scandinavian social housing.” I think he’s onto something. This is a picture from a housing development in Copenhagen. It is quite similar to what’s going up in Griffintown, with one key difference. In Copenhagen, there is green space. In Griffintown, there is none.

Part of the genius of Montreal is an almost utter lack of urban planning on

the grand scale. And in the case of Griffintown, the city has been almost negligent in its approach. During its overzealous attempt to approve any and all projects proposed by developers in Griffintown from about 2006 to 2010, the Ville de Montréal overlooked a few key components for the new neighbourhood: parks and schools. It was only after 2010 that the city thought that maybe it should earmark some land for, you know, parks. Schools? Who needs them?