Enfin, la justice & the narcissism of academic debate

December 18, 2008 § 2 Comments

So news has come that Théonaste Bagasora, a former colonel in the Rwandan army, was sentenced to life in prison for his actions in inciting the genocide there in 1994, in Arusha, Tanzania. The Rwandan government of Paul Kagamé (whose behaviour during the genocide remains open to debate) is pleased. Aloys Mutabingwa, a Rwandan government spokesperson, told Agence France-Presse that “En ce qui concerne Bagosora, la justice a été rendue. Nous sommes satisfaits.”

Part of what concerns me about the emergent view of the Rwandan genocide today is that the number of victims gets downplayed. Whilst the BBC reports that 800,000 ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus were massacred in the spring of 1994 in Rwanda, Canada’s own The Globe & Mail insists the numbers are closer to 500,000. What’s more interesting is that The Globe relies on the same Associated Press article that the Montreal Gazette does, but has downshifted the numbers from 800,000 to 500,000. This isn’t really news insofar as The Globe goes, the 500,000 figure has consistently been in their stories for at least the last few years. I once emailed The Globe’s Africa correspondent, Stephanie Nolen, but she never responded. Today, I have had an email exchange with the Foreign Desk Editor, but I haven’t really received a satisfactory response.

Of course, the 500,000 figure gets into a debate about start and end date of the Rwandan genocide. The accepted parameters here are the 100 days after President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down near the Kigali airport on 6 April 1994. In those 100 days, 800,000 people died. That’s 8,000 people killed every day for 100 days in Rwanda. I still shudder at that. Anyway. I guess that when we start debating 500,000 v. 800,000 killed, we start defining starting and ending dates of the genocide.

And, on one level, given the number of dead in Rwanda in a 90-day genocide is so astronomic, a difference of 300,000 is probably not a big deal, on another level, we are talking about 300,000 people, bludgeoned to death. The numbers are overwhelming, but these were still people. I guess my problem here is that I find myself overwhelmed by numbers when we discuss genocide and genocidal massacres, and the body counts just make my head swim. I took a course on genocide and human rights at the outset of my PhD and had to stop doing the readings because they were really just clinical listings of the dead. A few million here, 100,000 there, and so on. I suppose the only way to deal with genocide is to adopt a clinical tone, but I can’t do it. So the difference between 500,000 and 800,000 matters.

And while the Aegis Trust reminds us that the important thing to remember is that there was a genocide, I also think that we need to remember that 800,000 people lost their lives because of their political beliefs (in the case of moderate Hutus) or simply their ethnicity (in the case of the Tutsis). And that, my friends, is not right, it is abhorrent, it still makes me ill. One of the things most clearly seared into my head is Gen. Roméo Dallaire’s description of going to a meeting with this or that military commander, having to cross a river that had stopped flowing, so filled with bloated corpses it was. In short, we need to remember not just that there was a genocide, but that actual real people died. I think we forget that too quickly when we get into academic debates about start and end dates and so on.

shameless self-promotion

December 1, 2008 § Leave a comment

here is the link to the next ctlab event, a virtual symposium to be held 5-8 december in response to antoine bousquet’s new book, The Scientific Way of Warfare: Order and Chaos on the Battlefields of Modernity(London: Hurst & Co. Publishers; New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

the zero trope

November 27, 2008 § 6 Comments

so, about this time last year, mike was developing this idea of the zero trope with regards to the terrorist, the ground zero creating the terrorist. we had a lively exchange on the subject, mostly categorised by me playing the role i apparently am supposed to, which is the cranky historian historicising the discussion. anyway. last week, i was at a public lecture by katie gough, a visiting professor in irish studies at concordia university, on irish theatre, and a representation of the slave ship zong in elizabeth kuti’s 2005 play, the sugar wife.

in her talk, gough referred to the zong as the “ground zero” of the anti-slavery movement, due to the events on board the zong which resulted in the massacre of 60 african slaves in 1781. in other words, the zong was the event that lead to the beginnings of an anti-slavery movement in england and the rest of the british isles, culminating in the abolition of the slave trade in the united kingdom and its empire in 1833.

so this got me thinking about mike’s idea of the zero trope and terrorism, and since he’s probably the only person who bothers reading this blog, i’m sure he’ll have something to say in response. i argued last winter that finding a ground zero for terrorism is probably impossible, because all forms of terrorist activity owe some sort of debt to what came before them. al-qaeda is in the debt of the mujahaddin, who owe something to the viet cong, the plo owes something to the ira and the stern gang. and so on and so forth.

but, terrorism as a largely over-arching concept is one thing, but the terrorist is another. i’m still not entirely sure you can find one event, one moment that makes a terrorist. but maybe you can find one event, one moment that gives birth to a new movement? to take the example of the provisional irish republican army: it grew up in 1969, claiming to be a continuation of the irish republican army that had fought, first in the irish war of independence and then the irish civil war in the early 1920s. the provos, as they are called, argued that neither the republic or ireland nor the northern irish government were legitimate, and that only the 1919 irish republic is/was. and thus, they continued the fight to push the british out of ireland. the provos emerged out of a split of the irish republican army over abstentionism and the explosion of violence in derry and belfast in 1969. thus, we have a ground zero for the provisional irish republican army. sort of. because the provos are connected with the independence-era irish republican army. that body, however, is murkier in terms of defining whether or not it was a terrorist organisation because, of course, it won irish independence (though it lost the civil war, sort of, as the irish civil war was a battle between ira members who supported the treaty granting independence to ireland by britain and those who opposed the treaty). moreover, whilst forming an army for independence was a new one, sort of, in 1913, when the ira was founded, it grew out of the irish volunteers, a military organisation formed around the same time out of various other para-military secret societies agitating for irish independence in some shape or form. in other words, finding ground zero of an armed struggle for irish independence is nigh-on impossible, and the provisional ira claims to be a descendant of that struggle, as it argues that ireland is still not free and united, or at least it did before the current round of peace that has exited in ireland and northern ireland for the past decade. but even the last major terrorist act, that in omagh, northern ireland, in august 1998, was carried out by the real ira, itself a splinter group from the provos. and so on and so forth.

i guess, though, at the end of the day, what my problem with this trope is that it compartmenatlises too much, it breaks down and separates too much. terrorism is an ancient concept, and has existed as long as there has been organised violence. but individual terrorist groups, ok, maybe they do develop, but they don’t do so in a vacuum, the idea comes from somewhere. and that idea has historical antecedents, though perhaps they are cast anew with each new form.

but does this mean we can find the ‘ground zero’ of a terrorist, a terrorist organisation? of that i am not so sure.

this is wild

November 20, 2008 § Leave a comment

check out geoff manaugh’s bldgblog, for the latest on piracy in the high seas: http://bldgblog.blogspot.com/2008/11/piracy-live-at-sea.html

le monde virtuel et les soldats réels

November 20, 2008 § Leave a comment

on the trip into work today, i saw an interesting piece in le devoir about virtual training for canadian soldiers. according to le devoir, virtual training through army learning support centre at cfb gagetown in new brunswick ends up being cheaper than actual training for some functions. for example, to train a soldier to drive a tank, it usually costs close to 145,000$ per soldier in the real world, over the course of 6 weeks. but doing so virtually, costs only 96,000$, and it only takes two weeks. moreover, the success rate of the soldiers has shot up from 72% to 83%. according to capt. jeremy macdonald, who was interviewed at the Sommet international du jeu de Montréal, “plus de simulation, moins de terrain, plus de diplômés et moins d’argent: les chiffres parlent d’eux-mêmes et l’avantage de la formation virtuelle et s’avère indéniable.”

the centre has a staff 90 full-time, 20 contractors, and 30 interns from a nearby college. they support training for land forces in infantry, armour, artillery, tactics, as well as the canadian forces school of military engineering at cfb gagetown, as well as the canadian forces land advanced warfare centre, the canadian forces school of electrical and mechanical engineering and the canadian forces school of communications and electronics, all of which are in ontario.

given the continual budget crunch facing the canadian military, and i suppose, increasingly, all militaries, i think that the move to use virtual training instead of land training is an interesting one. i find myself wondering, in the case of the tank driver, if his virtual training is actually helpful for him in real life?

many of my students are gamers, and sometimes i wonder if their gaming experiences prepare them for or distort their interactions with reality, not necessarily because of whatever game they’re playing, but due to the virtual experience: it’s not real. it’s artificial and exists inside a computer. but is there a difference between that and the training of a soldier at cfb gagetown?

either way, i think it’s kinda neat.

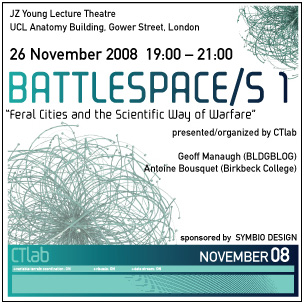

Upcoming CTlab event, 26 November in London, UK

November 8, 2008 § Leave a comment

For more details, check out the website of the complex terrain laboratory or the battlespaces page.

Landscape and the Housing Project

November 7, 2008 § Leave a comment

So, I’ve been pondering the housing project in North America, or the council estate in the UK, and the way it is constructed, the landscaping, and what this means. There are several projects of varying size in the neighbourhood I live in, and one set of PJs has me intrigued. There is a large central courtyard in the middle of this block. On the west side, there is 19th century working-class rowhousing (in this part of Montréal, these are predominately 2-story buildings), on the east side, the same. But on the southside is a small-scale housing project, an apartment block. On the northside, there is a series of similar apartment blocks. The courtyard in the middle one day when I wandered into it looked like I could be in any major North American city: Baltimore, New York City, Chicago, Toronto, Philadelphia just as much as I could be in Montréal. Cars on cinder blocks in the parking lot. Toys and debris littered across the grass. Some kids playing basketball, a boy and a girl hidden away in a corner looking for privacy, people on their balconys surveying the scene, a dude fixing his car blasting some bad hip hop (there is both good and bad hip hop).

A few weeks later, we were watching the American TV show, The Wire. The show, for a good deal of it anyway, is set in a housing project in Baltimore. The landscape was identical, though on a larger scale, to what I saw three blocks away in Montréal. So I got to thinking about the commonality of architecture in the housing project, and why that architecture became so universal, what it meant for notions of security, or at least what it was meant to mean for notions of security, and how Benthamite this all seemed to me.

To this end, in the coming weeks, I will be posting to the CTlab, once I put my thoughts on the housing project in some coherent order. Stay tuned!