Resurrecting Les Négresses Vertes

November 9, 2017 § 2 Comments

One of the wonderful things about growing up in Canada was official bilingualism. This meant, for example, that growing up in Vancouver, I could see my beloved Habs every Saturday night on La Soirée du Hockey on Radio-Canada. It also meant that the French-language version of MuchMusic, MusiquePlus, was broadcast across cable in Vancouver, direct from Montréal.

For the adventuresome young music fan, there was this whole other world out there from France, Belgium, Québec, and French Africa. Musiqueplus is how I first heard a whole raft of great French artists, from Youssou N’Dour to Noir Désire to Jean Leloup to Niagara to Serge Gainsbourg, and beyond. It is also how I first heard Céline Dion, so there’s that to take into account. But it is also how I first came across the great Parisienne band, Les Négresses Vertes.

In high school, French music wasn’t exactly something I could share with my friends. Sure, I was part of the alternative music crowd, but that only extended to the Anglophone world. I hunt out with some of the theatre kids, but this was a bridge too far even for them. It wasn’t until I moved to Ottawa, with its proximity to Montréal, that I found the freedom to enjoy French music publicly.

Most of the Anglo world first came across Les Négresses Vertes through their presence on the Red Hot + Blue album in 1990. They covered Cole Porter’s ‘I Love Paris.’ But, by then, I had already dug on their début album, Mlah, which came out in 1988. They were unlike anything I had ever heard in English. They mixed French traditional music with world beat and punk. They were complicated. Their melodies and beats owed more to the French Empire than France. And they had a strong sense of musicality, which bubbled up to the surface in surprising ways sometimes. Front man Noël Rota, better known as Helno, sounded a bit like Joe Strummer of the Clash, at least sometimes (this also made Strummer’s late life foray into acoustic punks and Latin beats somewhat bizarre to me, since it sounded more like Helno fronting Mano Negra).

The Vertes were a collection of misfits and punks from Paris, originating around Les Halles. They were a united nation of the former French empire; their name came from an insult hurled at them at one of their earliest. I don’t get romantic about the past and locations often, but, c’mon, this is Paris. Paris in the 80s must’ve been an amazing place. And Les Négresses Vertes arose out of this, the cosmopolitan nature of the French metropole, plus the distinct French qualities of the city, and the inner city at that. And the music! Aside from Les Négresses Vertes there was Noir Désir, Bérurier Noir, Mano Negra, amongst others.

Their first two albums, Mlah and Famille Nombreuse, teetered on complete chaos, an eight-piece orchestra. Helno was this tiny, kind of funny looking freak. He had a pompadour and looked like something that stepped out of the 1950s. But, in front of his band, he became something else. He held this chaos together. He was both the primary song writer and the vocalist. He sounded a bit like Strummer, yes, but he also sounded world-weary. All of this when he was in his late 20s. He’d done copious amounts of drugs, but he still more or less lived in his mother’s flat in a poor part of northern Paris. People all around him were dying, of suicide, drug overdoses, and AIDs. He once told a journalist that he through that if there was a Hell, it was on Earth. He also claimed that he wrote his lyrics whilst riding his bike around Paris, singing out loud as he rode. Hindsight says he was damned from the getgo. But I doubt it looked that way at the time.

His lyrics were riddled with slang and dark humour, stories of love and the gritty city (”Zobi La Mouche‘ and ‘Voila l’été‘) mixed with the occasional beautiful love song (‘Homme de marais‘, seriously one of my favourite songs ever) and dirge (‘Face à la mer‘). ‘Face à la mer’ was remixed by Massive Attack and became a huge club hit after Helno’s death (perhaps the most unlikely club raver ever).

It’s been a long time since I listened to the Vertes, probably close to a decade. But for some reason, I put them on last weekend. Nothing has changed, even though their first album was released almost 30 years ago. Helno himself has been dead for almost 25 years; he died of a heroin overdose in January 1993, at the age of 29. Their music is still immediate, still that beautiful concoction of chaos, danger, and beauty.

Les Négresses Vertes carried on after Helno’s death, eventually evolving more into a dub fusion band. But something was lost. Helno seemed to be the one who kept the chaos from falling off the rails, from ensuring the danger remained in the background. After his death, the band was never as exuberant and full of life again. They mellowed. And as much as I like the post-Helno era, for me, Les Négresses Vertes were at their best between 1987 and 1993.

As far as I know, they’ve never broken up, but they haven’t released any new music since 2001. They don’t have a web page. They don’t have a Twitter or a Facebook page. And career-spanning retrospectives were released in the early 2000s.

Equalization Payments in Canada

July 31, 2017 § Leave a comment

Over the weekend on Twitter, I was caught up in a discussion with an Albertan who didn’t believe that the province, along with British Columbia, is forecast to lead Canada in economic growth.

She argued that the province is still hurting, that big American gas companies had pulled out, and that people were leaving Alberta. Indeed, in June, Alberta’s unemployment rate was 7.4%, but even then, that was an improvement of 0.4% from May. But, economic growth does not mean that one can necessarily see the signs of a booming economy. Alberta’s economy, however, shows signs of recovery, and this 2.9% economic growth, as well as a decline in unemployment rates, shows that.

She also expressed a pretty common bitterness from Albertans about Equalization payments in Canada. These payments might be the most mis-understood aspect of Canadian federalism. The common belief in Alberta, which is usually a ‘have’ province (meaning it doesn’t receive equalization payments), is that its money, from oil and gas and everything else, is taken from it and given to the ‘have-not’ provinces (those who receive equalization payments). This is made all the more galling to Albertans because Quebec is the greatest recipient of equalization payments.

This argument, though, is based on a fundamental mis-understanding of how equalization payments work in Canada. Equalization payments date back to Canadian Confederation in 1867, as most taxation powers accrued to the federal government. The formal system of equalization payments dates from 1957, largely to help the Atlantic provinces. At that time, the two wealthiest provinces, Ontario and British Columbia, were the only two ‘have’ provinces. And this formal system was enshrined in the Constitution in 1982. Section 36, subsection (2) of the Constitution Act reads:

Parliament and the government of Canada are committed to the principle of making equalization payments to ensure that provincial governments have sufficient revenues to provide reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation.

The general idea behind equalization payments is, of course, that there are economic disparities across the nation. There is any number of reasons for these disparities, which are calculated on a provincial level. These can include the geographic size of a province, population, the physical geography, or economic activity.

Quebec is a traditional ‘have not’, which seems incongruous with the size and economy of the province. Montreal, after a generation-long economic decline from the late 1960s to the mid 1990s, has more or less recovered. If Quebec were a nation of its own (as separatists desire), it would be the 44th largest economy in the world, just behind Norway. It contributes 19.65% of Canada’s GDP. But Quebec’s economy is marked by massive inequalities. This is true in terms of Montreal versus much of the rest of the province. But it is also true within Montreal itself. Montreal is home to both the richest neighbourhood in the nation, as well as two of the poorest. Westmount has a median family income of $220,578. But Downtown Montreal ($32,841) and Parc Ex ($34,211) are the fourth and fifth poorest, respectively, in Canada.

The formula by which equalization payments are made is based on averages across the country. Here, we’re talking about taxation rates and revenue-generation, based on the national averages of Canada. Provinces that fall below these averages are ‘have not’ provinces. Those who fall above it are ‘have’ provinces. The three wealthiest provinces are usually Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta. But all three of these provinces have fallen into ‘have not’ status at various points. In 2017-18, in order of amounts received, the have-nots are: Quebec, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Prince Edward Island. Quebec, it should be noted, will receive more than the other ‘have-nots’ combined. The ‘have’ provinces this year are Alberta, British Columbia, Newfoundland & Labrador, and Saskatchewan.

The equalization payments, though, are not a case of taking money from Alberta to pay for Quebec’s social programs. The funds are not based on how much one province pays for its health care system, or for a universal child care system, or cheap tuition at the province’s universities (Quebec has both universal child care and cheap tuition for in-province students). Rather, the funds come out of the same general revenue stream that Ottawa has to fund ALL of its programmes and services. And, each and every Canadian contributes to this revenue stream. Thus, the fine people of Westmount contribute more to equalization payments (and general revenue) than the middle-class residents of suburban Calgary, or a person in a lower income bracket in Saskatchewan. And, because there are more Quebecers than there are Albertans, Quebec actually contributes more to the equalization payment scheme.

It is not just angry Albertans who believe they are getting hosed by the federal government. Many Quebecers will rail against their province’s funding priorities and point to the province’s status as a ‘have not’ as to why it should not have these programmes. Both positions are factually wrong, and based on a fundamental misunderstanding of Canada’s equalization payments.

Montréal: En construction

July 25, 2017 § 2 Comments

The running joke in Montreal is that a traffic cone should be our municipal symbol. From May to November or so annually, the streets of the metropole are a sea of traffic cones as workers frantically try to patch up roads thrashed by winter, and occasionally build something new. And annually, Montrealers kvetch about construction. As if it didn’t happen last summer and won’t happen next summer.

I was home last week, and it was the usual. Actually it’s beyond the usual. The city is awash in the orange beacons. Roads are dug up everywhere. But, something else occurred to me. This is not the status quo, this is not business as usual for my city. Instead, this is something new. This year, 2017, marks the 375th anniversary of the founding of the city in 1642. It is also Canada’s 150th anniversary since Confederation in 1867. This means that Montreal is seeing an infrastructural (re-)construction not seen since the late 1960s, in conjunction with Expo ’67, on Canada’s 100th anniversary. That boon saw the highway complex around the city built, as well as the Pont Champlain. Montreal also got its wonderful métro system out of that. But this infrastructural boom coincided with deindustrialization and the decline of the urban core of the city. Thus, what looked beautiful and shiny in 1967 had, by 2007, become decrepit and dodgy. There was no money for proper upkeep, so things were patched together.

Take, for example, the Turcot Interchange in the west end of the city. Chunks of concrete fell off it regularly, so there were these rather dodgy looking repair patches all over it. The Pont Champlain had outlived its expected lifespan of about 50 years. And the métro. Wow. While the trains still ran on time, more or less, and regularly, they were ancient.

The old Turcot Exchange. The different colourations of the concrete indicates patch work concrete, except, of course, for the rust and discolourations from water/ice.

But now, all this money is being showered on the city. The Turcot is being taken down and replaced with a level interchange. Work is on-going 24/7 on this. The old McGill University Health Centre (MUHC), which had been jerry rigged in a collection of century old buildings on avenue des Pins on the side of Mont-Royal, has a beautiful new campus on the location of the old Glen Rail Yards in NDG. The Pont Champlain is being replaced. Meanwhile, on the ride downtown on the Autoroute Bonaventure, on the A20 from the airport, one will find access to the downtown core blocked. The Bonaventure, a raised highway that bisects Griffintown (buy my book!) is being knocked down to be replaced with an urban boulevard. And while I am not entirely clear what the plans are for the Autoroute Ville-Marie under the downtown core, construction continues apace there. Meanwhile, the Société de transport de Montréal has new cars on the métro! At least on the Orange line. And, while they don’t actually feel air conditioned, they do have an effective air circulation system that, if you’ve ever experienced Montreal in the summer, you will appreciate.

Montreal’s new métro cars

So, for once, Montreal is not just being patched up. It is being rebuilt. For once, the powers-that-be have planned for the future of the city. And one day, who knows when, the city will be radically rebuilt and will have perhaps the most modern infrastructure in Canada, if not North America.

Go figure. No longer is my city a dilapidated, crumbling metropolis.

Publication: Griffintown: Identity & Memory in an Irish Diaspora Neighbourhood

June 12, 2017 § Leave a comment

At long last, my book, Griffintown: Identity & Memory in an Irish Diaspora Neighbourhood, is out from UBC Press. It is available in hardcover at present, though the paperback is coming in the fall.

I am particularly pleased with the cover and design of the book. The artwork on the cover come from my good friend and co-conspirator in Griff, G. Scott MacLeod. He and I have worked on The Death and Life of Griffintown: 21 Stories over the past few years.

I am particularly pleased with the cover and design of the book. The artwork on the cover come from my good friend and co-conspirator in Griff, G. Scott MacLeod. He and I have worked on The Death and Life of Griffintown: 21 Stories over the past few years.

Griffintown has long fascinated me not so much for the history of the neighbourhood, but the conscious effort by a group of former residents to reclaim it, starting in the late 1990s. I identified three men who were central to this process, all of whom have left this mortal coil in recent years: The Rev. Fr. Tom McEntee, Don Pidgeon, and Denis Delaney. These men worked very hard to make the rest of Montreal remember what was then an abandoned, decrepit, sad-sack inner-city neighbourhood. That Griff is known historically for its Irishness is a tribute to these men and many other former residents, most notably Sharon Doyle Driedger and David O’Neill, who worked tirelessly over the late 1990s and 2000s to reclaim their former home. The re-Irishification of Griffintown is the central story in my book. But I also look at the construction of Irish identity there over the 20th century, and the ways in which the Irish there performed every-day memory work to claim and re-claim their Irishness as they confronted their exclusion from Anglo-Montreal due to their poverty and Catholicism.

The Irish of Griffintown were fighters, they were insistent on claiming Home, even as that home disintegrated around them, due to deindustrialization and the infrastructural onslaught wrought by the Ville de Montréal, the Canadian National Railway, and the Corporation for Expo ’67. But, at the same time, they also left, seeking more commodious accommodations in newer neighbourhoods in the sud-ouest of the city, and NDG.

That these former residents could reclaim this abandoned, forgotten neighbourhood as their own speaks to the power of these people. These people were working- and middle- class men and women, ordinary folk from all walks of life, who were determined their Home not be forgotten. They re-cast Griff in their memories without the help of the state, without the help, to a large degree, of institutional Montreal.

I cannot over-state the impressive feat of these ex-Griffintowners. It has been a lot of fun to both study this process and work with and talk with many of those involved in this symbolic re-creation of Griff, drawing on an imagined history of Ireland and their own Irishness in the diaspora. And I am mostly relieved that the book is, finally, out.

Bonne fête à la charte de la langue française!

May 31, 2017 § 1 Comment

Bill 101 is 40 years old this year. For those of you who don’t know, Bill 101 (or Loi 101, en français) is the Quebec language charter. It is officially known as La charte de la langue française (or French-Language Charter). It essentially establishes French as the lingua franca of Quebec. For the most part, the Bill was aimed at Montreal, the metropolis of Quebec. Just a bit under half of Quebec lives in Montreal and its surrounding areas, and this has been the case for much of Quebec’s modern history. Montreal is also where the Anglo population of Quebec has become concentrated.

When Bill 101 was passed by the Parti québécois government of René Levésque in 1977, there was a mass panic on the part of Anglophones, and they streamed out of Montreal and Quebec, primarily going up the 401 highway to Toronto. My family was part of this. But we ultimately carried on further, to the West Coast, ultimately settling in Vancouver. At one point in the 1980s, apparently Toronto was more like Anglo Montreal than Montreal.

Meanwhile, back in the metropole, nasty linguistic battles dominated the late 1980s. This included actual violence on the streets. But there were also a series of court decisions, many of which struck down key sections of Bill 101. This, in turn, emboldened a bunch of bigots within the larger Anglo community, who complained of everything, from claiming Quebec wasn’t a democracy to, amongst some of the more whacked out ones, that the Anglos were the victim of ethnocide (I wish I was kidding).

But, in the 30 years since, much has changed in Montreal. The city settled into an equilibrium. And I would posit that was due to the economy. Montreal experienced a generation-long economic downturn from the 1970s to the 1990s. In the mid-90s, after the Second Referendum on Quebec sovereignty failed in 1995 (the first was in 1980), the economy picked up. New construction popped up everywhere around the city centre, cranes came to dominate the skyline. And then it seeped out into the neighbourhoods. By the late 90s/early 2000s, Montreal was the fastest growing city in Canada. It has since long since slowed down, and Montreal had a lot of ground to catch up on, in relation to Canada’s other two major cities, Toronto and Vancouver. But the economic recovery did a lot to stifle not just separatism, but also the more radical Anglo response.

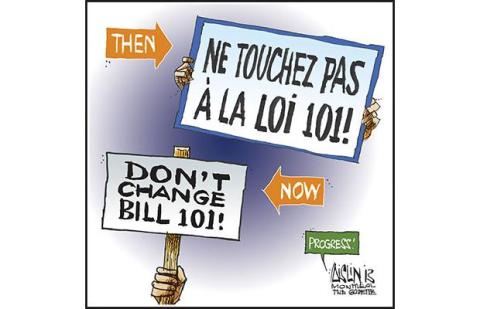

2013 editorial cartoon from the Montreal Gazette.

Last week, the Montreal Gazette published an editorial on the 40th anniversary of Bill 101. It was a shocker, as the newspaper was central to the more paranoid Anglo point-of-view, even as late as the mid-2000s. But, perhaps I should not have been surprised, as it was written by eminent Montreal lawyer, Julius Grey. He is one of the rare Montrealers respected on all sides. At any rate, Grey (who was also the lawyer in some of the cases that led to sections of Bill 101 being invalidated), celebrates the success of the Charte de la langue française. It has, argues Grey correctly, led to a situation where, in Montreal, both French and English are thriving. He also notes that there is much more integration now in Montreal than was the case in the 1970s, from intermarriage to social interaction, and economic equality between French and English. Moreover, immigrants have by-and-large learned French and integrated, to a greater or lesser degree, into francophone culture. Many immigrants have also learned English.

But the interesting part of Grey’s argument is this:

On the English side, dubious assertions of discrimination abound. It is important for all citizens to be treated equally, but often the problem lies in the mastering of French. The English minority has become far more bilingual than before, but many overestimate their proficiency in French, and particularly when it comes to grammar and written French. By contrast, francophones tend to underestimate their English.

In other words, speaking French is an essential to life in Montreal. And Anglos, I think, are more prone to over-estimating their French-language skills for the simple fact that it’s common knowledge one needs to speak the language.

Grey goes onto make an excellent suggestion:

These difficulties could be eased by the creation of a new school system, accessible to all Quebecers, functioning two-thirds in French and one-third in English. Some English and French schools would exist for those who do not wish to or cannot study in both languages, although most parents would probably prefer the bilingual schools.

However, this would never fly. The one-third English does not bely the demographics of the city (let alone the province, and I really don’t see the point of learning English in Trois-Pistoles). The urban area of Montreal is around 4 million (the population of Quebec as a whole is around 8.2 million). There are a shade under 600,000 Anglos in the Montreal region, largely centred in the West Island and southern and western off-island suburbs. That means Anglos are around 15% of the population of Montreal. The idea that Montreal is bilingual is given lie by these numbers.

Nonetheless, there is merit to this argument of an English-language curriculum in Quebec’s public schools (including in Trois-Pistoles). Like it or not, English is the lingua franca of the wider world, and global commerce tends to be conducted in that language. There is also the fact of the wide and vast English-language culture that exists around the globe. One of the things I enjoy about my own partial literacy in French (one that has certainly been damaged by not living in Montreal anymore) is the access to francophone culture, not just from Montreal and Quebec, but the wider francopohonie).

For any group of people or individual, there is a lot to be learned from bilingualism (or, multi-linguality). In Montreal (and Quebec as a whole), it could ensure that the city’s economic recovery in the past two decades continues. Along with this economic recovery has been a cultural renaissance in the city, in terms of music, film, literature, and visual arts. It is a wonderful thing to see Montreal’s recovery. And I want it to continue.

Update: Commemorating the Victims of the Irish Famine in Montreal.

May 29, 2017 § Leave a comment

Last week, the news out of Montreal was that the piece of land the Irish Memorial Foundation sought to create a proper memorial of the mass grave of Irish Famine victims had been sold to Hydro-Québec, which sought to build a power sub-station there, ironically to serve the burgeoning redevelopment of Griffintown.

But all is well that ends well, apparently. On Friday, Hydro-Québec and the Ville de Montréal issued a joint press release saying that they, along with Montreal’s Irish community, had come to an arrangement to see the redevelopment of a memorial to the 6,000 victims in that grave under what is now Bridge St.

And, frankly, it is about time that this project got underway.

Mis-Remembering the Patriotes

May 22, 2017 § 2 Comments

Today is the Journée nationale des Patriotes in Quebec. The date commemorates the 1837 Patriote Rebellion in what was then Lower Canada, when a rebellion against the British Empire erupted in first, Saint-Denis, and then other nearby locales in November and December of that year. And while it started off well for the Patriotes, it did not end well, with the British routing them and then ransacking the village of Saint-Eustache before martial law was imposed on Montreal.

But the rebellion only tells a part of the story of the Parti patriote. The Patriotes, led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, were a group of middle-class radicals, largely based in the urban centres of Lower Canada (Quebec). They took their inspiration from the French Revolution, and from the wave of liberal radicalism across the Western world, from France to the United States. They were frustrated with the corrupt politics of the Governor and his cadre.

From the early 1830s on, they formed the majority of the colonial legislature, which met in the capital of Quebec. The Patriotes sought, essentially, responsible government. They demanded accountability from the legislature and the governor. And they demanded economic development for the disenfranchised, disgruntled French Canadian majority of Lower Canada, as well as the working-class, predominately Irish, in Montreal and Quebec.

In other words, the Patriotes were not a French Canadian nationalist movement. I read an article in the Montreal Gazette yesterday that encapsulated my frustration with the memory of the Patriotes and 1837. The article was a discussion about what to call today in Quebec. The journalist noted that in the Montreal suburb of Baie d’Urfé, the citizens wish to call it La journee nationale des Patriotes/Victoria Day. This is not, obviously, an actual translation. The article then tours around the West Island and some off-island suburbs of Montreal that have a large Anglo population. The results are more of the same. And then there’s the title of the article, “Our Annual May Long Weekend Is Here. But What Should We Call It?” This, of course, is typical West Island Anglo code for their exclusion from the nation/province of Quebec, at least officially.

This is also a mis-remembering of the Patriotes. And not just by the West Island Anglos, but by almost every single Quebecer, whatever their background. And it is one that is rooted in our education system, not just in Quebec, but nationally. I learned, in school in British Columbia, that the Patriotes were only interested in French Canadians and were nationalists. When I taught in Quebec, my students had learned the same thing. I remember reading Allan Greer’s excellent book, The Patriots and the People, in grad school and being surprised at what I read.

Greer, in addition to noting the multi-ethnic background of the Patriotes, also is the one who made the argument that what 1837 was was a failed revolution in Quebec. That had the Patriotes succeeded, Quebec would’ve looked politically more like France or the United States. Indeed, it is in the aftermath of 1837 that the Catholic Church in Quebec came to be so powerful, as it became a member of the state in the province/nation, and gained great political, moral, economic, social, and cultural power over Catholic Quebecers, both English- and French- speaking, until the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s.

To return to the multi-ethnicity of the Parti patriote and its supporters, Papineau’s lieutenant was Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan, who was the member of the legislature for Montreal West. O’Callaghan succeeded the radical Dr. Daniel Tracey as the MLA for Montreal West and the right-hand seat at Papineau’s table. Both were Irishmen. Tracey died treating his compatriots in the fever shacks on Pointe-Saint-Charles during the cholera epidemic of 1832. Montreal West was the riding that contained Griffintown and other Irish neighbourhoods in what was then the west end of Montreal (now it’s the sud-ouest). The Griffintown Irish were radicals. They kept voting for Tracey and O’Callaghan over the wishes of their more genteel compatriots.

And then, there is the simple fact of the Brothers Nelson, Robert and Wolfred. They were the sons of English immigrants and members of the Anglo Protestant Lower Canadian bourgeoisie who were also major players within the Patriote movement. Wolfred led the rebels at the first battle of the Rebellion, at Saint-Denis on 23 November. This was the battle the Patriotes won. Robert, meanwhile, was amongst a group of Patriotes who were arrested and then freed in the autumn of 1837, which caused him to flee to the United States, where he was further radicalized. He led the 1838 Rebellion, which fizzled out pretty quickly. Both Nelsons survived the rebellions. Wolfred went on to become the Mayor of Montreal in the 1850s. Papineau, for his part, returned to the legislature after being granted amnesty in the 1840s.

Indeed, the major impetus for the formation of the St. Patrick’s Society of Montreal on 17 March 1834 was exactly this: the radical nature of the Griffintown Irish was hurting the larger ambitions of the Irish-Catholic middle class of the city. In those days, Montreal was not all that sectarian or linguistically divided. It was class that cleaved the city. Thus, the middle-class Anglo-Protestants, French Canadians and Irish all formed a community within the larger city, give or take the radicals. And they stood in opposition to and apart from the working classes, who tended to be more radical. Thus, the St. Patrick’s Society was created to separate the middle class Irish from these radicals. The Society was originally non-sectarian, it had both Catholics and Protestants within its ranks. It was not until the sectarian era of the 1850s that the Protestants were ousted.

It does all of us a dis-service to so clearly mis-remember the Patriotes. While Papineau is commemorated on streets, schools, highways, buildings, and a métro station in Montreal, the Nelsons, Tracey, and O’Callaghan are not. They have been removed from the officially sanctioned story of the Patriotes, let alone the 1837-8 Rebellions. Meanwhile, the Anglo community of Quebec seems to prefer to forget about the existence of these men entirely, to say nothing of the ancestors of many of us who voted for Tracey and O’Callaghan in Griffintown. Remembering the Patriotes for what and who they were would help with the divide in Montreal and Quebec.

Monumental History

May 11, 2017 § 19 Comments

I’m reading Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War. It’s an interesting read, as it posits the larger history of the Vietnam War, which includes the Vietnamese, as well as Laotians and Cambodians, are an essential part of the war story. Of course, that is bloody obvious. But, he is also right to note their elision from the official story of the Vietnam War in the US. He also objects to the fact that the very word ‘Vietnam’ in the United States means the Vietnam War. The entire history and experience of a sovereign nation is reduced to a nasty American war.

He spends a lot of time talking about the ethics of memory and an ethical memory in the case of the Vietnam War. And he is sharply critical of the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial in DC. He is critical because, as he notes, the memorial is 150 feet long and includes the name of the 58,195 Americans who died in service; if it were to include the Vietnamese dead, the wall would be nine miles long.

And so this brings up an interesting point about monuments and memory. There is a lot more to be said about this topic and, time permitting, I will return to this point in future posts. But what I want to consider here is the very nature of memorials. Memorials are either triumphalist or they are commemorative. They are constructed to recall glorious memories in our past. Or they are constructed to recall horrible events in our past.

In the former category, we have one of my favourite monuments, that to Paul de Chomedy, Sieur de Maisonneuve, and the other founders of Montreal. This is a triumphalist monument, with Maisonneuve surveying Place d’Armes from atop the monument, ringed with other early pioneers of Montreal: Lambert Closse, Charles le Moyne, and Jeanne Mance. And then, of course, there’s Iroquois, the single, idealized indigenous man. In the bas-relief between the four minor statues, the story of the founding of Montreal is told, sometimes with brutal honesty, such as the ‘Exploit de la Place D’Armes,’ which shows Maisonneueve with his gun to the throat of an indigenous warrior, as other warriors watch horrified.

In the former category, we have one of my favourite monuments, that to Paul de Chomedy, Sieur de Maisonneuve, and the other founders of Montreal. This is a triumphalist monument, with Maisonneuve surveying Place d’Armes from atop the monument, ringed with other early pioneers of Montreal: Lambert Closse, Charles le Moyne, and Jeanne Mance. And then, of course, there’s Iroquois, the single, idealized indigenous man. In the bas-relief between the four minor statues, the story of the founding of Montreal is told, sometimes with brutal honesty, such as the ‘Exploit de la Place D’Armes,’ which shows Maisonneueve with his gun to the throat of an indigenous warrior, as other warriors watch horrified.

The Maisonneuve monument was erected at Place d’Armes on 1 July 1895, Canada Day (or Dominion Day, as it was known then). Montreal had celebrated its 250th anniversary in 1892, and this monument was a product of that celebration.

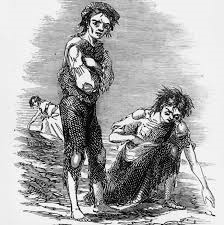

An example of a commemorative monument is the National Famine Monument, at Murrisk, Westport, Co. Mayo, Ireland. This monument was unveiled in 1997, on the 150th anniversary of Black ’47, the worst year of the Irish Famine (1845-52). The Famine saw close to half of Ireland either die (1 million) or emigrate (2 million). It is the birth of the great Irish diaspora, and remains one of the most catastrophic moments in the history of Ireland. The monument is stark, and looks frankly out of place, as a bronze model of a coffin ship sits in the green fields of Mayo. But it is designed to be haunting, a testament to the victims of the horrors of the Famine.

An example of a commemorative monument is the National Famine Monument, at Murrisk, Westport, Co. Mayo, Ireland. This monument was unveiled in 1997, on the 150th anniversary of Black ’47, the worst year of the Irish Famine (1845-52). The Famine saw close to half of Ireland either die (1 million) or emigrate (2 million). It is the birth of the great Irish diaspora, and remains one of the most catastrophic moments in the history of Ireland. The monument is stark, and looks frankly out of place, as a bronze model of a coffin ship sits in the green fields of Mayo. But it is designed to be haunting, a testament to the victims of the horrors of the Famine.

But what Nguyen is arguing for is an inclusive monument-making: one that honours both sides of an historical event. And so I find myself wondering what that would even look like, how it would be constructed, how it would represent both (or more) sides of an historical event. How would the historic interpretive narrative be written? What kind of language would be chosen? Monuments are already an elision of history, offering a sanitized version of history, even commemorative ones (such as the one in Co. Mayo, which most clearly does not discuss the policies of British imperialism in manufacturing a Famine in Ireland). So how is that historical narrative opened to include multiple points of view?

I don’t have the answers, but these are questions worth pondering.

21 Short Films About Griffintown

March 30, 2017 § Leave a comment

As regular readers will know, I have been working on the history and memory of Griffintown, Montreal for many years now. My book, Griffintown: Identity and Memory in an Irish Diaspora Neighbourhood, is out in May (the paperback will be out in the fall). And, of course, I have been working for a few years now with Montreal film-maker, artist, animator, and purveyor of all things creative, G. Scott MacLeod. Our project, 21 Short Films About Griffintown, is now up on the web for all to see.

This project is based on a walking tour of Griff Scott developed, and can be followed on your smart phone. We have 21 very short films of 21 sites around Griff, about their history and significance.

I like these clips, partly because Scott has done some great work contextualizing my stories of these sites with archival footage, his animations, and music, because all of this also minimizes my screen time. But also because it was a fun day that we spent wandering around Griff filming these. It was a hot August day in 2012, a day or two before I left Montreal for good. I had my dog, Boo, with me. He was all stressed out because of the move and had scratched his face raw. So he was with me because I had to keep him from scratching the infection. He trundled along with us in the 30C heat, usually with my foot on his leash as we filmed. Boo was a massive dog, around 150lbs, a Mastiff/Shepherd cross. He was a big, gentle giant. Boo died last year, so I see this project as a bit of a memorial to him, even if he doesn’t appear on screen.