Bringing the Past to Life

February 1, 2016 § Leave a comment

Twenty-odd years ago, I took a course on pre-Revolution US History at the University of British Columbia. I don’t know what possessed me to do this, frankly. It must’ve fit into my schedule. Anyway, it turned out to be one of the best courses I took in undergrad. It was taught by Alan Tully, who went onto become Eugene C. Barker Centennial Professor of American History at the University of Texas. We read a bunch of interesting books that semester, including one on the early history of Dedham, Massachusetts. But, the one that has always stuck out in my mind is Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s The Diary of a Midwife: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on her Diary, 1785-1812. I remember being deeply struck by this book as a 20-year old in Vancouver. I had a pretty strong interest in women’s history as an undergrad, but this was one of the best history books I’ve ever read.

In my last semester teaching at John Abbott College in Montreal, I taught US History, and assigned this book. I even got in touch with Dr. Tully to tell him how influential that course had been on me, and how influential this book had been and to thank him. I think he was chuffed to hear from me, even if he didn’t remember me (I wasn’t a great student,I barely made a B in his class).

I am teaching US History to 1877 this semester and I have assigned this book again. Last time I assigned in, in 2012, my students, much to my surprise, loved it. And they loved it for the same reasons I do. Ulrich does an incredible job showing the size of Martha Ballard’s life in late 18th century Hallowel, Maine.

Based on the singular diary of Ballard, Ulrich delves into the social/cultural history of Hallowel/Augusta, Maine, drawing together an entire world of sources to re-create the social life of Ballard’s world. I’m reading the book again for class, we have a discussion planned for today. I’m still amazed at how Ulrich has re-created Ballard’s world. And even if Ballard’s written English isn’t all that familiar to us today, 200+ years on, you feel almost like you’re in the room with Ballard. She has her own singular voice in my head, I feel like I know her.

Writing history isn’t easy. It is a creative act, attempting to bring to life things that happened 10 or 200 years ago. We work from disparate sources, with multiple voices, created for a multitude of different reasons. They agree with each other, they argue with each other. And it’s our job to bring all of this together. In many ways, we’re the midwives of the past. The very best History books are like The Diary of a Midwife or E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class: they bring the past to life. They make us feel almost like we were there.

The Sartorial Fail of the Modern Football Coach

January 13, 2016 § 2 Comments

As you may have heard, the University of Alabama Crimson Tide won the college football championship Monday night, defeating Clemson 45-40. This has led to all kinds of discussion down here in ‘Bama about whether or not Coach Nick Saban is the greatest coach of all time. See, the greatest coach of all time, at least in Alabama, is Paul “Bear” Bryant, the legendary ‘Bama coach from 1957 until 1982.

Bear won 6 national titles (though, it is worth noting the claim of Alabama to some of these titles is tenuous, to say the least). Saban has now won 5 (only 4 at Alabama, he won in 2003 at LSU). I don’t particularly give a flying football about this argument, frankly. But as I was watching the game on Monday night, everytime I saw Nick Saban, I just felt sad.

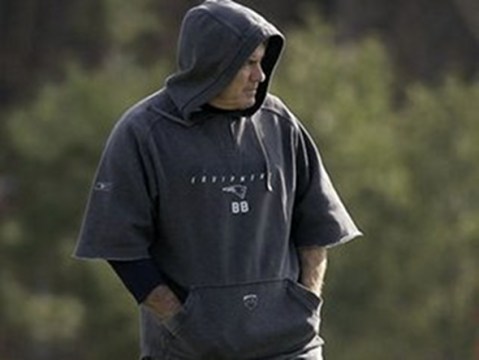

Nick Saban is a reasonably well-dressed football coach, so there is that. But, he looks like he should be playing golf. Poorly-fitting pants and and a team-issued windbreaker. He could be worse, he could be Bill Bellichk of the New England Patriots, who tends to look homeless on the sidelines.

Nick Saban is a reasonably well-dressed football coach, so there is that. But, he looks like he should be playing golf. Poorly-fitting pants and and a team-issued windbreaker. He could be worse, he could be Bill Bellichk of the New England Patriots, who tends to look homeless on the sidelines. But that’s not saying much, is it?

But that’s not saying much, is it?

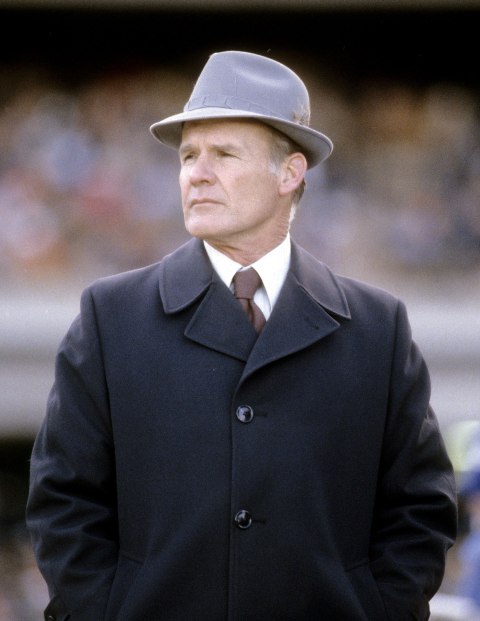

Saban and Bellichick are a far cry from Bear Bryant and Tom Landry, the legendary Dallas Cowboys coach. Bryant and Landry both wore suits on the side lines. Bryant did have an unfortunate taste for houndstooth, of course. But Landry stood tall in his suit and fedora.

There’s something to be said for looking sharp on the sidelines. I miss these well-dressed coaches.

Place and Mobility

January 8, 2016 § 7 Comments

I’m reading a bit about theories of place right now. And I’m struck by geographers who bemoan the mobility of the world we live, as it degrades place in their eyes. It makes our connections to place inauthentic and not real. We spend all this time in what they call un-places: airports, highways, trains, cars, waiting rooms. And we move around, we travel, we relocate. All of this, they say, is degrading the idea of place, which is a location we are attached to and inhabit in an authentic manner.

I see where these kinds of geographers come from. I have spent a fair amount of my adult life in un-places. I have moved around a lot. In my adult life, I have lived in Vancouver, Ottawa, Vancouver again, Ottawa again, Montreal, Western Massachusetts, Boston, and now, Alabama. If I were to count the number of flats I have called home, I would probably get dizzy.

And yet, I have a strong connection to place. I am writing this in my living room, which is the room I occupy the most (at least whilst awake and conscious) in my home. It is my favourite room and it is carefully curated to make it a comfortable, inviting place for me. It is indeed a place. And yet, I have only lived here for six months. In fact, today is six months sine I moved into this house. I have a similar connection to the small college town I live in. And the same goes for my university campus.

So am I different than the people these geographers imagine flitting about the world in all these un-places, experiencing inauthentic connections to their locales? Am I fooled into an inauthentic connection to my places? I don’t think so. And I think I am like most people. Place can be a transferrable idea, it can be mobile. Our place is not necessarily sterile. It seems to me that a lot of these geographers are also overlooking the things that make a place a place: our belongings, our personal relationships to those who surround us, or own selves and our orientation to the world.

Sure, place is mobile in our world, but that does not mean that place is becoming irrelevant as these geographers seem to be saying. Rather, it means that place is mobile. Place is by nature a mutable space. Someone else called this house home before me. This house has been here since 1948. But that doesn’t mean that this is any less a place to me.

The Ethno-Centrism of Psychology

December 30, 2015 § 6 Comments

I’m reading Jared Diamond’s most recent book, The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies?. Diamond, of course, is best known for his 1999 magnum opus, Guns, Germs & Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, a magnificent study of what led the Western world to dominance in the past several centuries. Diamond also kick-started the cottage industry of studies in World History that sought to explain how it was that the World came to dominate, and, in most cases, predicting the West’s eventual downfall. Some of these were useful reads, such as Ian Morris’ Why The West Rules For Now, and others were, well, not, such as Niall Ferguson’s Civilization: The West and the Rest.

At any rate, in his Prologue, Diamond talks about, amongst other things, psychology. He reports that 96% of psychology articles in major peer-reviewed, academic journals in 2008 were from Western nations: Canada, the US, the countries of Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Israel. Of those, 68% dealt with Americans. But it gets better, the vast majority of those were articles based on research where participants were undergraduates in psychology courses.

This is somewhat disconcerting as it means that the vast majority of what we know about human psychology from the academy is based on an ethno-centric, largely Americanized point-of-view. But, perhaps more damning, the majority of this opus is based on 18-22 year olds at universities across the US. That means these participants are predominately wealthy (relatively), American, and young.

Interestingly, we also know enough about the human brain and psychology to know that they evolve as we age. It is also clear from fields as diverse as history, psychology, anthropology, sociology, etc., that people are not all the same across cultures. In other words, applying what we may know about one issue, based on research on American undergraduates in psychology classes, has absolutely no bearing on elderly German men and women. Or, for that matter, middle-aged Chinese women.

How We Remember: Siblings and Memory

November 9, 2015 § 15 Comments

My wife and I are watching the BBC show Indian Summers. It’s about the British Raj in 1930s India and its summer retreat at Simla, in the foothills of the Himilayas. The show centres around Ralph Whelan, an orphan who has risen in the British civil service in India to become the Personal Secretary to the viceroy, as well as his sister, Alice who has mysteriously shown up in Simla, leaving behind some murkiness. Alice, you see, was married, and she claimed her husband is dead. However, it turns out he is not. I don’t know how this turns out yet, we’re only 5 episodes in.

But what interests me is the relationship between siblings. Ralph is the elder child, though it’s not entirely clear how big a difference in age there is between he and Alice. Nevertheless, it is big enough to make a huge difference in their upbringing. It’s also not clear when their parents died. Both Ralph and Alice were born in India, but Alice was sent back to England when she was 8, presumably when their parents died. She has only recently returned to the colony. Ralph, it appears, has spent most of his life in India.

The memories of Ralph and Alice of their childhood are radically different. In the first episode, Ralph manages to have dug out a rocking horse that Alice apparently loved as a child. She has no recollection of it. And this sets the pattern. Every time Ralph recalls something from their childhood, Alice responds with a blank look. At one point, she says “I didn’t have the same upbringing” as Ralph did.

I found myself thinking about the relationship between siblings and memory. Halbwachs notes the social aspect of memory, how we actually form our memories in society, not individually. In her acknowledgements to her graphic novel, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, Alison Bechdel provides a hint to the disparate memories of siblings when she thanks her family for not objecting to her publishing the book. In Fun Home, Bechdel ponders her father’s death against the discovery that he was closeted, all the while she figures out her own sexuality and comes out. Her memory of the events, and the way it is told, is carefully curated. She controls the entire story, obviously, as its her story. But, clearly, the hint is that her siblings (to say nothing of her mother) might remember things differently.

Even in my own family, largely due to the 5 1/2 years separating me from my younger sister and the 12 1/2 years between my brother and I, it often feels like we grew up in three different families. I remember things differently than my sister, and we both remember events differently than our brother does. Even events all three of us clearly remember, there are wide disparities in how we remember things go down.

As the experiences of the fictitious Whelan siblings, the real Bechdels, and me and my siblings, the existence and function of memory in a family counters Halbwachs’ claims about the formation of a collective memory. Indeed, given the strife that tends to exist in almost all families, it is clear that perhaps the formation of memories and narratives in families works differently tan in wider society.

The Myth of the ‘Founding Fathers’

November 2, 2015 § 1 Comment

Rand Paul got in trouble recently for making up quotations he attributed to the Founding Fathers. In other words, Paul is making a habit of lying to Americans, in attempting to get their votes, by claiming the Founding Fathers said something when, in fact, it’s his own policies he’s shilling. Never mind the fact that Paul says “it’s idiocy” to challenge him on this, he, in fact, is the idiot here.

The term “Founding Fathers” has always made me uncomfortable. Amongst the reasons why this is so is that the term flattens out history, into what Andrew Schocket’s calls ‘essentialism’ in his new book, Fighting over the Founders: How We Remember the American Revolution. (I wrote about this book last week, too). The term “Founding Fathers” presumes there was once a group of men, great men, and they founded this country. And they all agreed on things.

Reality is far from this. The American Revolution was an incredibly tumultuous time, as all revolutions are. Men and women, fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, brothers, sisters, disagreed fundamentally about a multitude of issues, not the least of which was whether or not independence was a good idea or not. Rarely taught in US history classes at the high school or university level, loyalists, at the end of the War of Independence, numbered around 15-20% of the population. And there is also the simple fact that less than a majority actively supported independence, around 40-45%. The remaining 35-45% of the population did its best to avoid the war or independence, for a variety of reasons.

The Constitutional Congress, then, did not speak for all the residents of the 13 Colonies, as many Americans seem to believe. The Articles of Confederation and the Constitution were fraught affairs, with many of the men involved in their drafting in staunch opposition to each other. Aside from ego, there were deep, fundamental differences in thought. In other words, the Constitution was a compromise. The generation of men (and the women who influenced them, like Abigail Adams) who created the United States were very far from a unified whole, whether in terms of the larger population, or even within the band of men who favoured and/or fought for independence.

Thus, the term “Founding Fathers” is completely inadequate in describing the history of this country between c. 1765-1814. But, then again, most Americans tend to look back on this period in time and presume a single ethnicity (British) and religion (Protestantism) amongst the majority of residents of the new country. In fact, it is much more complicated than that, and that’s not factoring in the question of slavery.

It’s not surprising that Americans would wish a simple narrative of a complex time. Complexity is confusing and it obfuscates even more than it shows. And clearly, for a nation looking at its founding myths, complexity (or what Schocket would call ‘organicism’) is useless. You cannot forge myths and legends out of a complicated debate about independence, government, class, gender, and race. It’s much simpler to create a band of men who looked the same, talked the same, and believed the same things.

But, such essentialism obscures just as much as complexity does when it comes time to examine the actual experience of the nascent US during the Revolution. The disagreements and arguments amongst the founders of the country are just as important as the agreements. The compromises necessary to create a new country are also central. I’m not really a big believer in historical “truths,” nor do I think facts speak for themselves, but we do ourselves a disfavour when we simplify history into neat story arcs and narratives. Unlike Schocket, I do think there is something to be gained from studying history, that there are lessons for our own times in history, at least to a degree: the past is not directly analogous to our times.

Of course, as a public historian, this is what I love to study: how and why we re-construct history to suit our own needs. So, perhaps I should applaud the continuing need for familiar tropes and storylines of the founding of the US.

Partisanship and American Politics and History

October 28, 2015 § 4 Comments

I am reading Andrew Schocket’s fascinating new book, Fighting Over the Founders: How We Remember the American Revolution, for a directed reading I’m doing with a student on Public History. I’m only about 45 pages into the book, but so far, it is very compelling reading, and also re-confirms my decision to walk away from a planned research project into the far right of American politics and its view of the country’s history.

Schocket argues that since the 1970s, Americans and American life and culture have become more partisan. He points to the internet, the dissolution of the Big Three networks’ monopoly on the news, self-contained internet communities, and the rise of ideological political spending outside of the two main parties (i.e.: the result of SCOTUS’ incredibly wrong-headed Citizens United decision). He also notes gerrymandering, and the evidence that suggests Americans are moving into ideologically similar communities.

I have never really bought this argument. This country’s entire political history has been based on political partisanship. Sure, the Big Three networks have lost their monopoly, but the bigger issue is the end of the FCC’s insistence on equal time for opposing viewpoints on the news. But even then, newspapers were little more than political organs in the 19th century. Self-contained communities in both the real world and the internet really only replace 19th and 20th century workplaces where people were likely to think similarly in terms of politics. True, Citizens United is a new wrinkle, but it doesn’t really change much in terms of partisanship.

We are talking about a country where the initial founding was controversial, as evidenced by the 20% of the population who were Loyalists during the Revolution. Then, during the first Adams administration, the Alien & Sedition Acts were passed for entirely partisan reasons. I’m not sure you can find an example in US history of a more partisan moment than one where those in power attempted to outlaw the political discourse of their rivals. This country also nearly came apart in the 1860s over what was, in part, a partisan divide between Democrats and Republicans. Republicans didn’t get elected in the South in the ante-bellum era. The South did not vote for Lincoln. Many Northern Democrats, the so-called copperheads, had Southern sympathies. Or there’s the tension between Democrats and Republicans in the early 20th century over the power of corporations. Or how about the battle over America’s place in the world after World War I? What about the McCarthyite era?

In short, while we live in an era of intense partisanship, this is nothing new for the United States. Partisanship is, in many ways, as American as baseball, apple pie, and Budweiser.

Freedom Isn’t Free

September 30, 2015 § 5 Comments

Here in the United States, it is common to see a bumper sticker that says “Freedom Isn’t Free.”  These stickers pre-date 9/11 and the War on Terror and the devastating human cost of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. But they have taken on special meaning in the decade-and-a-half since 9/11.

These stickers pre-date 9/11 and the War on Terror and the devastating human cost of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. But they have taken on special meaning in the decade-and-a-half since 9/11.

I am, as usual, teaching American history this semester. One of my classes is reading David Roediger’s classic book, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. While Roediger’s attempts to connect himself to EP Thompson are perhaps overdone, he still makes a powerful argument about the centrality of race in the development of a free labour ideology in the US. He especially ties his argument to WEB DuBois’ conclusion in his Black Reconstruction of the psychological benefit the white worker received (in lieu of fair wages) through his whiteness, and its pseudo-entry to power.

Roediger digs back into what he calls the pre-history of the American worker, the period between colonization and the dawn of the 19th century and the beginnings of the American industrial revolution. This involves a discussion of the compromise over slavery in the Constitution. Roediger writes:

Even artisan-patriots with substantial anti-slavery credentials supported the Constitution as a compromise necessary to secure the world’s greatest experiment in freedom.

Indeed. The freedom of white Americans, especially white American artisans/workers in the Revolutionary era came at the cost of the enslavement of African Americans. On one hand, Roediger seems to be letting these artisan-patriots off the hook. On the other, I have never quite understood the apparent lack of irony in the Revolutionary generation’s easy resort to slavery rhetoric to complain of Britain’s treatment of the colonies. I find it preposterous and disingenuous. And yet, this rhetoric became powerful during the Revolution. At any rate, as Roediger reminds us, freedom isn’t free.

A Little Learning is a Dangerous Thing

September 25, 2015 § 7 Comments

Alexander Pope once opined that “A little learning is a dangerous thing.” We can see multiple examples of this almost daily. But, it was truly brought home to me on Twitter last weekend. Against my better judgement, I got into a discussion that became an argument over discrimination against the Irish in Canada. My interlocutor was dead set on presenting the thesis that the Irish were the lowest of the low well into the 20th century and the infamous NINA (No Irish Need Apply) signs were ubiquitous across our fair Dominion. To back up her argument, she cited her grandparents, who reported seeing the NINA signs when they arrived (I’m not sure when they arrived, but she was roughly my mother’s age, a Baby Boomer, so I would hazard her grandparents arrived in the 1920s), a random page from a House of Commons debate where then-Prime Minister Sir John A. MacDonald denigrated the Irish in 1889, and a screen cap from an historical newspaper aggregator that reported some 30,000 NINA mentions in Canada. But the time frame was not clear.

This kind of logic would not pass a freshman course. In short, she cherry-picked her evidence to back up her thesis. Now, I know a thing or two about a thing or two when it comes to the Irish in Canada, a result of a Master’s thesis and a PhD dissertation (and forthcoming book) about the Irish in Quebec, from the 1840s to the 21st century. I have read nearly every book on the Irish in Canada (and North America as a whole) as part of the process leading to the MA and PhD. Her basic thesis, that the Irish were discriminated against is not wrong. But this argument is largely limited to the 19th century, and more than that, to the middle decades of the 19th century. Certainly, discrimination continued to plague the Irish in Canada beyond, say, 1880, but, by then, the Irish were also successfully integrating into Canadian society, through accommodations from the dominant Anglo-Protestant culture, through accommodations made by the Irish themselves, and by the Irish forcing themselves into the Canadian body politic. As the 19th century drew to a close, the Irish had infiltrated the corridors of power in Canada, both politically and economically. But this does not mean that all discrimination went away.

First, she essentialized my argument, claiming that I said that NO discrimination occurred after 1900, as if the turning of the century was some magic boundary. And then she produced this cherry picked evidence, which I countered with the larger argument, pointing to both individual and cultural successes. She claimed that Toronto was different than Montreal. That is correct. But, I countered with information on the plight of the Irish in Toronto. No luck. She was convinced she was right. I didn’t go so far as to get pedantic and explain how history is made/written/produced, but when I rejected her argument, she accused me of calling her grandparents liars. At this point, I cut my losses and muted her on Twitter.

All I could do was shake my head and ponder why and how so many people are so resistant to logic and reason. It’s not like I’m innocent of this, either. Recently, an argument broke out on the Facebook wall of one of my friends about the level of integration of Anglophones in franco-québécois culture. All three of us arguing were ex-pat Montrealers, all three of us Anglos. All three of us have PhDs, in other words, we should’ve known better. Instead, we devolved into anecdotal evidence, personal stories, and ignored the meta-data all three of us are very familiar with on the matter. So while we did not, like my interlocutor on Twitter, devolve into cherry-picking our evidence, we still engaged in #logicfail.

My point in telling this second story is to point out we all do this. But there is great danger in this. It leads to an American populace that thinks that Ben Carson is right when he says that the President cannot be Muslim because Islam is incompatible with the Constitution. And still greater ills.

Residential Segregation

September 23, 2015 § 2 Comments

Sometimes I’m shocked by segregation, in that it still exists. It exists in Canada. Don’t believe me? Look at East Vancouver, the North Side of Winnipeg, the Jane-Finch corridor in Toronto, or Saint-Michel in Montreal. But, in the US it is even more shocking. Boston was the most racist place I’ve ever seen, the casual racism of Bostonians towards black people, the comments on BostonGlobe.com. Or the fact that people told me that The Point, an immigrant neighbourhood of Salem, MA, was a place where “you can get shot.” Or the simple fact that residential segregation was very obvious in and around Boston. Unless you take public transit (as in the bus or the subway), you could live your entire life in Boston without noticing people of colour there.

Down here in Alabama, though, it’s not a simple question of race, class is also central to residential segregation. I live in a small city (so small, in fact, that my neighbourhood in Montreal is about the same size as this city in terms of population). I live in a neighbourhood that is comfortably middle-class, veering towards upper-middle class the closer you get to the university. But, in the midst of this, there are a few blocks that look like something you’d expect to see in the 1920s in a Southern city. These images below are from one of these streets, a block behind my house. These houses are essentially a version of a shotgun house. The block behind me is about 70% black, 30% white. It is also full of abandoned houses, empty lots, and lots with the ruins of homes. The street itself is about a car-width wide, and where I come from, would be called a back alley.

What is perhaps most shocking to me is how an apartment complex (which my neighbours all eye suspiciously) ensures this segregation with fencing designed to keep the riff raff out. To me, the very clear segregation of this block is shocking. Almost as surprising and shocking this block is in the midst of my neighbourhood. For example, the final photo is of the next block over from this street.

What is perhaps most shocking to me is how an apartment complex (which my neighbours all eye suspiciously) ensures this segregation with fencing designed to keep the riff raff out. To me, the very clear segregation of this block is shocking. Almost as surprising and shocking this block is in the midst of my neighbourhood. For example, the final photo is of the next block over from this street.